Bureaucratic rationality #3: Indecent Exposure edition

With apologies to Max Weber and H. L. Mencken.

IN NOVEMBER 2004, LUCY WIGHTMAN BEGAN RECEIVING anonymous e-mails that threatened to unravel the life she had crafted as a psychologist in two affluent Boston suburbs. It was, by all accounts, a good life. Her practice, South Shore Psychology Associates, was thriving, with an office first in Hingham, then in Norwell. In addition to her adult clients, children came after school, referred by pediatricians, school counselors, and fellow psychologists. She was liked in part because she was more laid-back than your typical psychologist. She didn’t wear makeup, and dressed in flowing skirts and turtleneck sweaters during her meetings with patients. Often her dog, Perry, was by her side.

My daughter,says one Braintree mother,fell in love with her at first sight.… LUCY WIGHTMAN USED TO BE KNOWN AS PRINCESS CHEYENNE, a stage name she was given, she says, by a strip-club owner. Back in the 1970s and ’80s, she welcomed notoriety, but that kind of attention was not going to be as good for her new career. In early 2005, three months after Wightman received the first threats, Princess Cheyenne was back in the news, her story broadcast on Fox 25 Undercover, as the e-mail writer had promised. Three days later, the state Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation announced that investigators were trying to determine if Wightman, in presenting herself as a psychologist, had broken the law.

Then, on October 6, the state attorney general’s office and a Suffolk County grand jury came down hard. Wightman was indicted on 26 counts of felony larceny, six counts of filing false health-care claims, six counts of insurance fraud, and one count of practicing psychology without a license. Michael Goldberg, the president of the Massachusetts Psychological Association and a psychologist in Norwood, compares it to a surgeon operating without a medical license.

… When Al Deluca, 38, began seeing Wightman in the summer of 2003 to talk about his marital problems, he says Wightman told him not to file an insurance claim because she was not licensed. Many patients, however, believed that she was. The word

psychologywas in her business name, and that, according to Eric Harris, a lawyer for the Massachusetts Psychological Association, is enough to put an unlicensed practitioner in violation of the law. Her e-mail address isDr. Wightman.Her billing statements are printed withLucy Wightman, Ph.D.… While a person can legally practice psychotherapy without a license in Massachusetts, state law requires that psychologists have a degree in psychology from a state-recognized doctoral program and that they be licensed with the state Division of Professional Licensure. Licensed psychologists must also have two years of supervised training. They must take specific courses, pass an exam, and meet continuing-education standards long after they have tacked their degrees to the wall.

… “I HAVE A FULL CASE LOAD RIGHT NOW,” WIGHTMAN E-MAILED IN mid-November. She was talking about her practice, still running and apparently still prospering. The name has changed. It’s now called South Shore Psychotherapy, a notable distinction legally. The people who come to see her don’t care what she calls herself.

She made a mistake, I think, in using the wordAl Deluca says.psychologyin her business name. But I don’t think what she did warrants all the attention and all the charges that have been levied against her,I think Lucy is being used. If this whole thing about her being a stripper had never come out, then this would have died.

(Link thanks to Lori Leibovich @ Broadsheet (2006-01-27).)

If we didn’t have the State to enforce guild rules and save us all from the dire threat of people calling themselves psychologists

instead of psychotherapists

without a permission slip, who would? If the government won’t stand up to keep people from suffering unauthorized conversations about their problems with a smart, warm, laid-back adviser that they like to talk to, then who will?

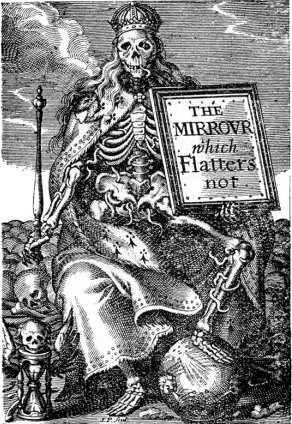

Bureaucratic rationality, n.: The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may have something good in their life without permission.