Burn Corporate Liberalism

AlterNet’s recent article, Why Atheist Libertarians are Part of America’s 1 Percent Problem is mostly remarkably only in how utterly, thoughtlessly awful it is. Of course many political libertarians are conservative tools, and this includes those who are anti-religious. But the bulk of this article is a series of undirected polemical jabs and cheap partisan talking-points attacking Ayn Rand, Ron Paul, Penn Jillette and Michael Shermer in the most formulaic and uncharitable possible terms; in general the article might be a candidate for the Ridiculous Strawman Watch, but mostly it is just a demonstration, as Nathan Goodman says, that the author couldn’t pass an ideological Turing test.

I do want to mention the following, though — because the pull-quote manages to take just about everything I despise in American liberalism and wrap it up into one tight little package:

. . . Atheists who embrace libertarianism often do so because they believe a governing body represents the same kind of constructed authority they've escaped from in regards to religion. This makes sense if one is talking about a totalitarian regime, but our Jeffersonian democracy, despite its quirky flaws, is government by the people for the people, and it was the federal government that essentially built the great American middle-class, the envy of the world. . . .

–CJ Werleman, Why Atheist Libertarians Are Part of America’s 1 Percent Problem

AlterNet, December 3, 2013.

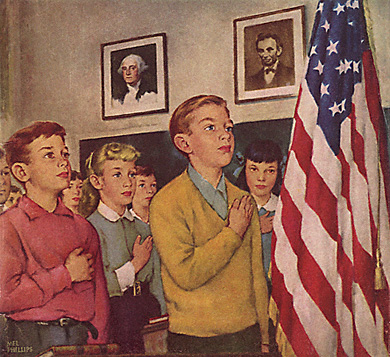

Yes, indeed. Here is a completely mythical, wildly unrealistic civics-textbook Disney cartoon[1] of how American government works. It has a few kinks here and there in the real world application, but it’s vouched for by the idealistic fantasies of a prestigious racist, expansionist slave-owning Democratic President. You know that it works great because through a stupendous effort of subsidy and social regimentation it has created the most privileged bourgeoisie the world has ever known. America, fuck yeah!

This is what happens when you take corporate liberalism and expose it to gamma radiation. In all seriousness, it is absolutely true that the construction of the white American middle class

was one of the biggest and most effective projects of the United States government over the past 80 years. And in every aspect — the world-empire militarization; the cartelized, permanent warfare economy; the border controls; the internal segregation; the subsidized white flight, car culture and Urban Renewal; the Junior-G-man ethos and the law-and-orderist socioeconomic policing; the stock-market bail-outs and the logic of Too Big To Fail;

the institutionalization of everyday life and the full-spectrum pan-institutional promotion of patriarchal family, bourgeois respectability and bureaucratic meritocracy

— the political manufacture of the white American middle class

has been one of the most reactionary, destructive, dysfunctional, patriarchal and racist campaigns that American government has ever waged against human liberty, and the basic justification of every one of its most grievous assaults on the oppressed, exploited and socially marginalized.

Of course the federal government created the great [white] American middle class.

To the eternal shame of both.

- [1]Actually, John Sutherland Productions. Sutherland spent three years as a director for Disney before he went on to produce propaganda films for the D.O.D. and then for Harding College (on a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation).↩