More from Venezuelan anarchists on the current wave of protest and government repression. I started translating Rafael Uzcategui’s recent, extremely helpful overview Resumen express de la situaci?@c3;b3;n venezolana para curioso/as y poco informado/as

but I found that a translation had already been done by the author himself, and reposted by volunteers at the anarchist activist blog ROAR.[] The translation is his work. I have, however: (1) restored some boldface emphasis from the original Spanish that was left out in the translation, (2) made editorial revisions to a few isolated phrases that I thought reflected careless errors or were potentially misleading (with editorial notes where I made any changes), (3) re-added a P.S.

at the very end of the article which was omitted from the English translation, and, (4) to fit the usual format at this blog, I’ve added the headline back in. (Any editorial changes I’ve made, after the headline, are explicitly noted.) This one is translated by the author himself, but as with previous translations, if you notice any issues with the translation feel free to point them out in the comments, and I’ll attach an editorial note or correction to the text here.

Rafael Uzcategui

On February 4th, 2014, students from the Universidad Nacional Experimental del Táchira (Experimental University of Táchira), located in the inland state of the country, protested the sexual assault of a fellow female classmate, which took place in the context of the city's increasing insecurity. The protest was repressed, and several students were detained. The next day, other universities around the country had their own protests requesting the release of these detainees, and these demonstrations were also repressed, with some of the activists incarcerated.

The wave of indignation had as context the economic crisis, the shortage of first necessity items and the crisis of basic public services, as well as the beginnings of the imposition of new economic austerity measures by President Nicolás Maduro. Two opposition politicians, Leopoldo L?@c3;b3;pez and María Corina Machado, tried to capitalize on the wave of discontent rallying for new protests under the slogan "The Way Out" and also tried to press for the resignation of president Maduro. Their message also reflected the rupture and divisions on the inside of opposing politicians and the desire to replace Henrique Capriles' leadership, who publicly rejected the protests. The Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (Democratic Unity Table) coalition, didn't support them either.

When the government suppressed the protests, it made them grow bigger and wider all over the country. On February 12th, 2014, people from 18 cities protested for the release of all of the detainees and in rejection of the government. In some cities of the interior, particularly punished by scarcity and lack of proper public services, the protests were massive. In Caracas, three people were murdered during the protests. The government blames the protesters, but the biggest circulating newspaper in the country, ?@c3;161;ltimas Noticias, which receives the majority of its advertising budget from the government itself, revealed through photographs that the murderers were police officers. As a response to this, Nicolás Maduro stated on national television and radio broadcast that police enforcement had been "infiltrated by the right wing."

The repression of the protesters draws not only on police and military enforcement agencies; it also incorporates the participation of militia groups to violently dissolve the protests. A member of PROVEA, a human rights NGO, was kidnapped, beaten and threatened with death by one of them on the west side of Caracas. President Maduro has publicly encouraged these groups, which he calls colectivos (collectives).

The Venezuelan government currently[] controls all of the major TV stations, and has threatened with sanctions radio stations and newspapers that transmit information about protests. Because of this, the privileged space for the distribution of information have been the social media networks, especially Twitter. The use of personal technological devices has allowed record-keeping through videos and photographs of ample aggressions of the repressive forces. Human rights organizations report detainees all over the country (many of them already released). The number has surpassed 400, and they have suffered torture, including reports of sexual assault, cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment. As this is being written 5 people have been murdered in the context of the protests.

In his speeches, Nicolás Maduro incites[] the protesters opposing him to assume even more radical and violent positions. Without any ongoing criminal investigation, he automatically stated that everyone killed has been murdered by the protesters themselves, who he disqualifies with every possible adjective.

However, this belligerence seems not to be shared by all the chavista movement, because a lot of its base is currently withholding its active support, waiting to see what will come next. Maduro has only managed to rally public employees to the street protests he has called. In spite of the situation and due to the grave economic situation he faces, Nicolás Maduro continues to make economic adjustments, the most recent being a tax increase.

The state apparatus reiterates repeatedly that it is facing a "coup", that what happened in Venezuela on April 2002 will repeat itself. This version has managed to neutralize the international left-wing, which hasn't even expressed its concern about the abuses and deaths in the protests.

The protests are being carried out in many parts of the country and are lacking in center and direction, having being called through social media networks. Among the protesters themselves, there are many diverse opinions about the opposition political parties, so it's possible to find many expressions of support and also rejection at the same time.

In the case of Caracas the middle class and college students are the primary actors in the demonstrations. On the other hand, in other states, many popular sectors have joined the protests. In Caracas the majority of the demands are political, including calls for the freedom of the detainees and the resignation of President Maduro, while in other cities social demands are incorporated, with protests against inflation, scarcity and lack of proper public services. Even though some protests have turned violent, and some protesters have fired guns at police and militia groups, the majority of the protests, especially outside of Caracas, remain peaceful.

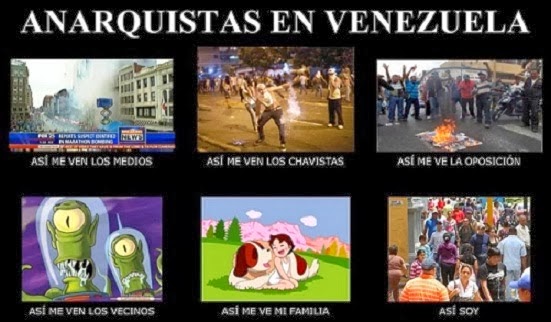

The independent revolutionary left in Venezuela (anarchists, sections of Trotskyism and Marxist-Leninist-Guevarism) has no involvement in this situation, and we are simple spectators.[] Some of us are actively denouncing state repression and helping the victims of human rights violations.

Venezuela is a historically oil-driven country. It possesses low levels of political culture among its population, which explains why the opposition protesters have the same "content" problem as those supporting the government. But while the international left-wing continues to turn its back and support — without any criticism — the government's version of "a coup", it leaves thousands of protesters at the mercy of the most conservative discourse of the opposition parties, without any reference to anti-capitalists, revolutionaries and true social change that could influence them.

In this sense, Leopoldo L?@c3;b3;pez, the detained conservative opposition leader, tries to make himself the center of a dynamic movement that, up to the time of this writing, had gone beyond the political parties of the opposition and the government of Nicolás Maduro.

What will happen in the short term? I think nobody knows exactly, especially the protesters themselves. The events are developing minute by minute.

For more alternative information about Venezuela, we recommend:

P.S. If you want to read about the elements that contradict the possibility that there would be a coup d’etat in Venezuela, I recommend you read: https://rafaeluzcategui.wordpress.com/2014/02/17/las-diferencias-de-abril/[]

— Resumen express de la situaci?@c3;b3;n venezolana para curioso/as y poco informado/as (Feb. 21, 2014). Translated by the author, Rafael Uzcategui, with minor editorial revisions by Charles W. Johnson.