Over My Shoulder #21: Kathie Sarachild, “The Power of History,” in Feminist Revolution (1975)

You know the rules. Here’s the quote. This is from The Power of History by Kathie Sarachild, the leading essay from Feminist Revolution, an insightful, indispensable, and sometimes infuriating anthology published in 1975 by the Redstockings; the essay is, among other things, a kind of memo on where the anthology as a whole is coming from and why the Redstockings thought it was so important to put it together:

The grass-roots appeal of feminism has been reflected in the composition of liberal feminist organizations like NOW as well as in the mass response to the radical ideas and agitation.

Yet the radical, feminist women faced opposition all the way, with constant advice from all sides that everything they were doing would have the opposite effect: that it would raise antagonism and bitterness, tat it was unrealistic and would get nowhere, that it wasn’t speaking to where women were at.

What lay behind the successful plans and strategies of the women’s liberation activists, what kindled the wonderful explosion, was simply their commitment to a radical understanding and approach to feminism, to discovering the common issues facing women and addressing them directly at their deepest level. They were not playing political games, trying to figure out whether women or men were ready for this or that, whether this or that would be understood or be popular.

This was going to be a movement in our own self-interest, as we said. This was going to be a fight for ourselves, for our own immediate lives, as well as for our dreams — a movement growing from our own experience, addressing the problems we ourselves had encountered. But a fundamental part of this effort to better understand our own situation was the radical understanding that the conditions in our own lives we wanted to change were essentially the common situation for women. This understanding of ourselves was going to be essential to the common fight because it was what put a person in touch with the common fight, connected a person directly to the common fight. We wanted to

change the worldout of our own self-interest, and because we had such a strong sense of this being in our interest, we felt sure we could convey this sense to all who shared the same interests.With all our talk about self-interest, it was, of course, all along common interest that we were talking about, the common interest of women.

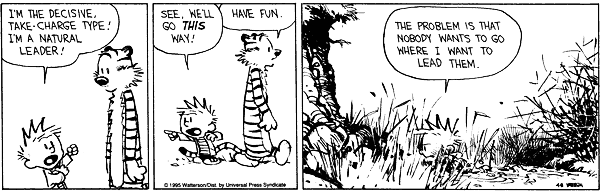

The intensity of our belief that our own personal interest arose out of the common situation was what made usknow that there would be no conflict between standing up for our own impulses and desires and analysis growing out of our own situation, and launching a mass movement. All the politicking, the guessing at the popularity of this or that, the feasibility of this or that with one group or another, would build nothing, really. It would fail to turn women on and maybe even turn them off. We knew this because we acknowledged our own most honest reaction.

The radical, feminist interest in developing and disseminating theory–in raising and spreading consciousness–was scorned, even attacked, by the liberal feminists and non-feminist left alike, who were always calling for

actionand for whom no amount of action we engaged in was ever even acknowledged. They were always posing it as analysis versus action, and priding themselves in being the activists, or thepoliticos,or the steady, on-going workers who accomplished tangible, concrete gainsin the community,in the nation,for themselves, or what not. They always implied that the radical,theorypeople (as they would sometimes complain about us) didn’t take any action, didn’t produce any actual changes in the everyday lives of women.

Don’t agonize, organizewas a favorite one liner. Of course, when stated asDon’t analyze, organizea lot of the punch goes out of it.Oddly enough, there was also the totally contradictory charge, usually from the

left,that the women’s liberation movementneeded some theory,hadn’t produced any theory.Just as the actions of the radical feminists were not seen as actions–they were toopetty,too sporadic, or what not–their analysis was not seen as analysis or theory.What we were trying to do was to advance and develop both theory and action, and to unite them, putting theory into action and action into theory. It was this commitment to unity of the two, of course, which made us radicals, and which made us such a threat to liberals, right and

left,who had a hard enough time recognizing and supporting feminism in either the realm of theory or action–and who apparently went blank or haywire when confronted with the combination.Whatever we were doing just never seemed to fall within the range of the liberal left’s vision. But in the beginning it did fall within the range of the TV cameras and newspapers.

In fact, it was the public actions of the radicals, the consciousness-raising section of the movement, that put the WLM on the map. This was true of virtually every category of action you could name–from confrontation, consciousness-raising actions like the picketing and disruption of the Miss America Contest to developing techniques for mass organizing to producing journals, newspapers and books which were widely disseminated.

But the radical theory and strategy was not only the source of widespread mobilization, was not only what sparked the interest of the masses of women, it was also what produced the most in the way of concrete results, the most changes in women’s lives. This is another lesson of the past decade whose truth comes clear with access to an authentic history of the movement. The greatest achievements of the women’s liberation movement so far, those that have reached the masses of women as a whole–greater freedom in the area of birth control and abortion, greater freedom from oppressive dress codes, and the spread of feminist theory and consciousness–were all the arenas the radicals first addressed and in which they led.

It was in New York State, the area in which radical feminist analysis, action and organizing ideas were strongest and most advanced, that the first concrete breakthrough of the women’s liberation movement in the U.S. was achieved–the abortion law reform which for a few years turned New York State into

the abortion mill of the nationand upon which the U. S. Supreme Court modeled its guidelines a few years later. It was the radical strategies of 1) opposition to reform and demand for repeal, led by Lucinda Cisler 2) mass consciousness-raising on abortion with women testifying to theircriminalacts in public and in court 3) the development of the feminist self-help clinic ideas and their promotion of simpler, new abortion techniques that led to the nationwide reform in five years time.The area of employment, on the other hand, is one in which the liberal feminist groups have concentrated and so far have led, and in which there has been as yet very little progress–for most women anyway. (See New Ways of Keeping Women Out of Paid Labor in this book.)

Knowing these things provides information, support and strength for a continuing radical approach and further radical action. But virtually none of it is known.

As soon as the movement began and proved successful, a process set in of wresting control from the women who had started out. And as certain approaches in the movement proved to be popular and successful with other women, the process began of confusing who and what had produced those successful approaches, what thinking, what inds of people, and specifically which people. There was an assault on the history of the movement–to take it over, to lasso it for one’s private ends, to slow it down, to stop it.

Many of the simplest and most powerful elements of the movement’s history I listed earlier have disappeared from sight or the connections between them have been severed. Instead, an array of secondary versions, interpretations and revisions have effaced and replaced the original record.

There are now amazingly different stories of these events, with very different beginnings and very different conclusions. One version doesn’t even have women starting the movement but

historyandchanging timesstarting it instead. Ifhistoryorchanging timesisn’t behind the changes thentechnologyis, orthe economy.The rise of the feminist movement reflected a certain historic context, but this context had to be unlocked by analysis in order to be opened up for attack and work.

The knowledge of who started the movement contains important political lessons for women as does the knowledge of what brought women their gains. That women started the movement and gave it its strength and momentum suggests that it was necessary for women to start the movement, that men would not start the movement, that men don’t lead women to their freedom. Women must rely on themselves for that–not because they

shouldbut because they have to.–Kathie Sarachild, The Power of History, from Feminist Revolution: An Abridged Edition with Additional Writings (1975/1979), pp. 18–21.

It might not seem like a poetry reading from Rudyard Kipling is the most promising way to commemorate ongoing events in South Asia. But, by jingo, he did

It might not seem like a poetry reading from Rudyard Kipling is the most promising way to commemorate ongoing events in South Asia. But, by jingo, he did  The

The