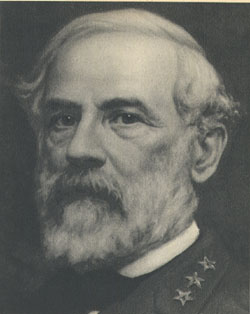

Robert E. Lee owned slaves and defended slavery

Note added 2010-02-02. Since I originally wrote this article in 2005, it has attracted a great deal of attention through Google and become a common reference point for people looking for information on Robert E. Lee’s opinions and practices when it came to slavery. In order to help people who come here for information on Lee, I’ve since added a series of links at the bottom of this article on other things I’ve written and discovered concerning Lee’s views and experience on race and slavery since this article was originally written.

I’ve spent some time ragging on neo-Confederate mythistory here before; today I’d like to take a bit of time to talk about another of the idiot notions popular with the Stars-and-Bars crowd: the idea that Robert E. Lee opposed slavery, or that he didn’t own any slaves. No he didn’t, and yes he did. Robert E. Lee defended the institution of slavery and personally owned slaves.

Lee cheerleaders love to point out that Lee wrote to his wife, in 1856, that In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil

He did write that, but the use of the quotation is dishonest. The quote is cherry-picked from a letter that Lee wrote to his wife on December 27, 1856; the passage from which it was taken actually reads:

In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.

—Robert E. Lee, letter to his wife on slavery (December 27, 1856)

Lee, in other words, regarded slavery as an evil

–but a necessary evil ordained by God as the white man’s burden

. Far from expressing opposition to the institution of slavery, the purpose of his letter was actually to condemn abolitionists; the letter was an approving note on a speech by then-President Franklin Pierce, which praised Pierce’s opposition to interference with Southern slavery, and declared that the time of slavery’s demise must not be sped by political agitation, but rather left to God, with whom two thousand years are but as a Single day.

After that reassuring note, Lee goes on to offer an impassioned plea for toleration of the Spiritual liberty

to enslave an entire race:

Although the Abolitionist must know this, & must See that he has neither the right or power of operating except by moral means & suasion, & if he means well to the slave, he must not Create angry feelings in the Master; that although he may not approve the mode which it pleases Providence to accomplish its purposes, the result will nevertheless be the same; that the reasons he gives for interference in what he has no Concern, holds good for every kind of interference with our neighbors when we disapprove their Conduct; Still I fear he will persevere in his evil Course. Is it not strange that the descendants of those pilgrim fathers who Crossed the Atlantic to preserve their own freedom of opinion, have always proved themselves intolerant of the Spiritual liberty of others?

And what did the painful discipline … necessary for their instruction

mean? One of the sixty-three slaves that Lee inherited from his father-in-law explains:

My name is Wesley Norris; I was born a slave on the plantation of George Parke Custis; after the death of Mr. Custis, Gen. Lee, who had been made executor of the estate, assumed control of the slaves, in number about seventy; it was the general impression among the slaves of Mr. Custis that on his death they should be forever free; in fact this statement had been made to them by Mr. C. years before; at his death we were informed by Gen. Lee that by the conditions of the will we must remain slaves for five years; I remained with Gen. Lee for about seventeen months, when my sister Mary, a cousin of ours, and I determined to run away, which we did in the year 1859; we had already reached Westminster, in Maryland, on our way to the North, when we were apprehended and thrown into prison, and Gen. Lee notified of our arrest; we remained in prison fifteen days, when we were sent back to Arlington; we were immediately taken before Gen. Lee, who demanded the reason why we ran away; we frankly told him that we considered ourselves free; he then told us he would teach us a lesson we never would forget; he then ordered us to the barn, where, in his presence, we were tied firmly to posts by a Mr. Gwin, our overseer, who was ordered by Gen. Lee to strip us to the waist and give us fifty lashes each, excepting my sister, who received but twenty; we were accordingly stripped to the skin by the overseer, who, however, had sufficient humanity to decline whipping us; accordingly Dick Williams, a county constable, was called in, who gave us the number of lashes ordered; Gen. Lee, in the meantime, stood by, and frequently enjoined Williams to

lay it on well,an injunction which he did not fail to heed; not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done. After this my cousin and myself were sent to Hanover Court-House jail, my sister being sent to Richmond to an agent to be hired; we remained in jail about a week, when we were sent to Nelson county, where we were hired out by Gen. Lee’s agent to work on the Orange and Alexander railroad; we remained thus employed for about seven months, and were then sent to Alabama, and put to work on what is known as the Northeastern railroad; in January, 1863, we were sent to Richmond, from which place I finally made my escape through the rebel lines to freedom; I have nothing further to say; what I have stated is true in every particular, and I can at any time bring at least a dozen witnesses, both white and black, to substantiate my statements: I am at present employed by the Government; and am at work in the National Cemetary on Arlington Heights, where I can be found by those who desire further particulars; my sister referred to is at present employed by the French Minister at Washington, and will confirm my statement.—Testimony of Wesley Norris (1866); reprinted in John W. Blassingame (ed.): Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, and Interviews, and Autobiographies Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press (ISBN 0-8071-0273-3). 467-468.

Some Lee hagiographers seem to be completely unaware that Lee ever owned slaves, much less treated them like this. Part of that’s just the warping of tidbits they heard elsewhere–it’s true that Lee did not own any slaves during most of the Civil War–and part of it is, frankly, dishonest fudging–Lee’s sixty-three slaves were, in spite of being legally under his control and forced to work on his plantation, not held under his own name, but rather temporarily under his control as an inheritance from his father-in-law, G.W.P. Custis. Other Lee cheerleaders recognize that Lee did own slaves, but give him props for manumitting them. What they leave out of the record is that Custis’s will legally required Lee to emancipate the slaves that passed into his control within five years of Custis’s death. Custis died October 10, 1857 and his will was probated December 7, 1857 (about a year after Lee wrote his letter on slavery); Lee kept the slaves as long as he could, and finally filed the deed of manumission with Court of the City of Richmond on December 29, 1862–five years, two months, and nineteen days after Custis’s death.

Custis actually gave freedom to his slaves without qualification in his will; the matter of the five years was supposed to be time for Custis’s executors to do the legal paperwork for emancipation in such manner as may to [them] seem most expedient and proper

. There’s good reason to read the clause as intending for the five years to serve as an upper bound on settling the legal details, not as five more years for driving the slaves for whatever last bits of forced labor could be gotten. Lee, however, did not see it that way, and set the slaves to for his own profit for as long as he could. We have already seen that some of the slaves disagreed with Lee on this point of legal interpretation, and how he treated those who acted on their legal theory by seceding from his plantation.

Of course, Lee never was very big on secession at all. Those who love to haul out the Confederacy — Lee included — as heros for secessionist self-determination tend to neglect comments such as this one:

Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our constitution never exhausted so much labor, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation, and surrounded it with so many guards and securities, if it was intended to be broken by every member of the Confederacy at will. It was intended for

perpetual unionso expressed in the preamble, and for the establishment of a government, not a compact, which can only be dissolved by revolution, or the consent of all the people in convention assembled. It is idle to talk of secession. Anarchy would have been established, and not a government, by Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison, and the other patriots of the Revolution.–Robert E. Lee, letter, 23 January 1861

Secession allowed; anarchy established, and not a government; one sighs–if only.

Robert E. Lee is no hero. He was a defender of slavery and a harsh critic of abolitionism; he was also a slaver who brutally punished those who sought their rightful freedom. There are many reasons to damn the Federal government’s role in the Civil War, but none of them offer any excuse for celebrating vicious men such as Lee.

Update 2005-07-03. Since this page is written for Google, I’ve made a couple revisions: (1) The title has been lengthened from Robert E. Lee owned slaves

to Robert E. Lee owned slaves and defended slavery,

to more accurately reflect the full contents, and the full text and a link to an online transcription of the Testimony of Wesley Norris was added..

See also:

- Comment (2005-10-07): Two more letters on the Norrises, and Lee’s letters denying wrongdoing [added 2010-02-02]

- GT 2006-02-24: Michael Fellman’s discussion of Lee’s experience with slavery [added 2010-02-02]

- GT 2006-05-28: Over My Shoulder #25: Lee's views on Reconstruction and civil rights, from Michael Fellman (2000), The Making of Robert E. Lee [added 2010-02-02]

- GT 2006-05-25: How Robert E. Lee’s army treated black soldiers [added 2010-02-02]

- GT 2006-03-24: Michael Fellman (2002), The Making of Robert E. Lee, on the Lee’s views on colonizationism [added 2010-02-02]

- Comment (2007-11-05): Some documentary notes on the 1850 and 1860 census [added 2010-02-02]

- GT 2005-06-26: Lost Causes

Roderick finds the spectacle of

Roderick finds the spectacle of