Let the hand-wringing begin

Nobody likes to have an abortion, and nobody would like to have one even under the best of conditions. Things are much better now than they were in the dark days of back-alley butchers; and they could be made much better yet if it weren’t for miles of punitive regulations and red tape made with the explicit purpose of making abortions harder for legally vulnerable women to obtain. But even without the cultural bullies and screaming protestors, even without the government-imposed cartel costs and the intense curtailment of options for procedures, your choices would still in the end be between invasive surgery of some form or another or drugs that make you nauseous and bleeding over the course of a few days. Of course abortion is not the horrendous experience that anti-choicers repeatedly make it out to be; it is far safer and quicker and easier on both patient and provider than nearly every other kind of surgery that there is. It’s safer and less psychologically taxing than giving birth. (Somehow these comparisons don’t seem to get made very often by either the anti-choice leadership or their foot soldiers. How strange.) But root canals are very safe and relatively simple too; that doesn’t mean that anyone is excited to have one.

But so what? Nobody goes around talking about the terrible tragedy of root canals either, or about the need to reach across the divide to unite with the anti-root-canal community (I take it that there are some Christian Scientist types who oppose dental surgery out of deeply felt religious conviction) in order to prevent unwanted tooth decay. Nobody feels the need to prefix every remark about their support for the right to get a root canal with a half-hour of qualifications and apologies. Yet the Party Hack wing of the Democratic leadership seems to have decided, yet again, that this is just what they need. Here, for example, is how Hillary Rodham Clinton decided to celebrate the anniversary of one of the greatest political triumphs for women’s liberation in recent history:

In a speech to about 1,000 abortion rights supporters near the New York State Capitol, Mrs. Clinton firmly restated her support for the Supreme Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion nationwide in 1973. But then she quickly shifted gears, offering warm words to opponents of legalized abortion and praising the influence of “religious and moral values” on delaying teenage girls from becoming sexually active.

There is an opportunity for people of good faith to find common ground in this debate — we should be able to agree that we want every child born in this country to be wanted, cherished and loved,Mrs. Clinton said.Her speech came on the same day as the annual anti-abortion rally in Washington marking the Roe v. Wade anniversary.

…

Mrs. Clinton, widely seen as a possible candidate for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 2008, appeared to be reaching out beyond traditional core Democrats who support abortion rights. She did so not by changing her political stands, but by underscoring her views in preventing unplanned pregnancies, promoting adoption, recognizing the influence of religion in abstinence and championing what she has long called

teenage celibacy.She called on abortion rights advocates and anti-abortion campaigners to form a broad alliance to support sexual education — including abstinence counseling — family planning, and morning-after emergency contraception for victims of sexual assault as ways to reduce unintended pregnancies.

We can all recognize that abortion in many ways represents a sad, even tragic choice to many, many women,Mrs. Clinton told the annual conference of the Family Planning Advocates of New York State.The fact is that the best way to reduce the number of abortions is to reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies in the first place.

Most of this is true enough, as far as it goes. Nobody wants abortion instead of widesperad contraception and responsible sexual education. Nobody likes to get an abortion. And in the present political and cultural climate, all too many women are made to feel far worse about their decision to have an abortion than should be. Fine. But the latter isn’t an unchangeable given; it’s a political fact that is enforced by a constant and intentional climate of harassment and intimidation. And the fact that we’d rather women were able to avoid unwanted pregnancy in the first place is no reason to spend hours hand-wringing over it and apologizing for it unless you already think that there’s something wrong with getting an abortion. But why should you think that?

Actually, there is one other reason that you might do all that hand-wringing. You might be cavilling in spite of your own beliefs because you think that kind of dissembling is politically useful. I hate to say it about Hillary — she gave such a great speech at the March and all — but it’s hard to know what else to conclude about this particular strategy:

Mrs. Clinton’s address came as the Democratic Party itself engages in its own re-examination of its handling of the issue in the wake of Senator John Kerry’s loss in the presidential race.

Democratic senators such as Harry Reid of Nevada and Dianne Feinstein of California have also pressed for a greater focus on reducing unintended pregnancies, and some Democratic consultants have urged that party leaders mint new language to reach voters who identified moral values as a top issue for them in last November’s election.

Jesus Christ people. Look. No. Just, no.

First, you’re not trying to mint new language. You’re repeating the same crap that you did for the past 12 years. Here, for example, is how Electable

John Kerry answered questions on abortion during the second and third debates:

Mr. Schieffer Senator Kerry a new question for you. The New York Times reports that some Catholic archbishops are telling their church members that it would be a sin to vote for a candidate like you because you support a woman’s right to choose an abortion and unlimited stem call research. What is your reaction to that?

Mr. Kerry I respect their views. I completely respect their views. I am a Catholic. And I grew up learning how to respect those views, but I disagree with them, as do many. I believe that I can’t legislate or transfer to another American citizen my article of faith. What is an article of faith for me is not something that I can legislate on somebody who doesn’t share that article of faith. I believe that choice, a woman’s choice is between a woman, God and her doctor. And that’s why I support that. Now I will not allow somebody to come in and change Roe v. Wade. The president has never said whether or not he would do that. But we know from the people he’s tried to appoint to the court he wants to. I will not. I will defend the right of Roe v. Wade.

Now with respect to religion, you know, as I said I grew up a Catholic. I was an altar boy. I know that throughout my life this has made a difference to me. And as President Kennedy said when he ran for president, he said, I’m not running to be a Catholic president. I’m running to be a president who happens to be Catholic. Now my faith affects everything that I do and choose. There’s a great passage of the Bible that says What does it mean my brother to say you have faith if there are no deeds? Faith without works is dead. And I think that everything you do in public life has to be guided by your faith, affected by your faith, but without transferring it in any official way to other people. That’s why I fight against poverty. That’s why I fight to clean up the environment and protect this earth. That’s why I fight for equality and justice. All of those things come out of that fundamental teaching and belief of faith. But I know this: that President Kennedy in his inaugural address told of us that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own. And that’s what we have to – I think that’s the test of public service.

And before that in the second debate:

DEGENHART: Senator Kerry, suppose you are speaking with a voter who believed abortion is murder and the voter asked for reassurance that his or her tax dollars would not go to support abortion, what would you say to that person?

KERRY: I would say to that person exactly what I will say to you right now.

First of all, I cannot tell you how deeply I respect the belief about life and when it begins. I’m a Catholic, raised a Catholic. I was an altar boy. Religion has been a huge part of my life. It helped lead me through a war, leads me today.

But I can’t take what is an article of faith for me and legislate it for someone who doesn’t share that article of faith, whether they be agnostic, atheist, Jew, Protestant, whatever. I can’t do that.

But I can counsel people. I can talk reasonably about life and about responsibility. I can talk to people, as my wife Teresa does, about making other choices, and about abstinence, and about all these other things that we ought to do as a responsible society.

But as a president, I have to represent all the people in the nation. And I have to make that judgment.

Now, I believe that you can take that position and not be pro-abortion, but you have to afford people their constitutional rights. And that means being smart about allowing people to be fully educated, to know what their options are in life, and making certain that you don’t deny a poor person the right to be able to have whatever the constitution affords them if they can’t afford it otherwise.

That’s why I think it’s important. That’s why I think it’s important for the United States, for instance, not to have this rigid ideological restriction on helping families around the world to be able to make a smart decision about family planning.

You’ll help prevent AIDS.

You’ll help prevent unwanted children, unwanted pregnancies.

You’ll actually do a better job, I think, of passing on the moral responsibility that is expressed in your question. And I truly respect it.

Apparently the apparatchiks have decided that there isn’t enough hand-wringing and pandering to the sensibilities of the Religious Right there. I don’t know how you could add any more hand-wringing and searching for “common ground” with the Christian Right there without the references to a woman’s right to an abortion disappearing entirely, but there you have it.

Guess what? It didn’t work then and it won’t work now. Why in the world do they think that it would? Are they trying to win votes from the Christian Right? Do they honestly think that moving the political debate over reproductive freedom back from abortion to the Sanger-era fights over birth control and sex education is going to improve the political climate in this country?

In other words: stop treating the right to abortion like you treat free speech rights for the Klan. If you don’t think there’s anything wrong with abortion then quit hemming and hawing forever about how much you respect the position of people who do and how much you’d like to work with them on birth control. You’re wasting your time: a lot if not most ofthem also hate birth control and sex education anyway. And in the process of wasting your time you are also dissembling about your real motives and spitting on women’s struggle for freedom.

Incidentally, Rox, among the reasons I like Howard Dean as much as I do is that in the heat of an election, this is how he answers a question about abortion:

Diane Rehm: We have seen reports that builders across the country are refusing to participate in the construction of Planned Parenthood buildings. What would you do about the threats to freedom for a woman to choose?

Howard Dean: Well, I think that’s a very dangerous game those builders are playing, especially in the city of Austin, which is where it’s going on. Were I down there I would immediately refuse to do business with any of the contractors who were boycotting that. So all groups can play that game; you have the right-wingers playing the game today, but other groups who may disagree with that can also play that game. And I think that’s a mistake for them to do that.

I am pro-choice. I’m a doctor; I frankly believe that it’s none of the government’s business to interfere in a woman’s making decisions about her own healthcare. And I tend not to be very supportive of efforts to enforce political points of view on individuals’ healthcare, and that’s what’s going on in Austin, Texas.

— On the Diane Rehms show, WAMU, 2004-12-01 10:00am (they don’t seem to have a transcript; the question is around 45’45” on the audio version)

Elsewhere he’s also directly, and without apology or cavil, taken on both parental consent restrictions and late-term abortion bans, and pointedly insisted that on the issue of abortion, We can change our vocabulary but I don’t think we ought to change our principles.

.

Second, even if this were a new tack, and even if there were any reason to believe that it would get anything worth accomplishing accomplished, why would you think that women’s control over their own bodies is an acceptable bargaining chip? Women are not pawns to be sacrificed for better board position. Lots of Democrats bolted the party in the late 1960s to become Republicans because the national leadership would no longer keep silent about Jim Crow and the efforts of efforts such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party finally broke the Eastland-Wallace white supremacist stranglehold on the Southern state parties. That lost the Democrats a lot of voters. The difference even lost them several elections. So what? Does anyone think that it would be a good idea to endlessly fret about how to reach out across the divide and find common ground to bring the Klan vote back into the party?

To hell with that. If you’re going to get hung up on winning political office, this is not how you should be trying to do it. Falling back on the apparatchiks and electable

candidates using electably

mealy-mouthed rhetoric doesn’t work and it wouldn’t have gained anything worth winning even if it did. Meanwhile, the other side won’t believe it, your side won’t pull out the stops for you, and the people in the middle won’t know where the hell you actually stand.

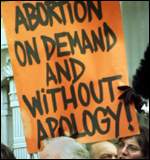

If Democrats are looking for new language with which to frame the abortion debate, I’d like to suggest a good old standard: ABORTION ON DEMAND AND WITHOUT APOLOGY.

![[photo: Anarchists]](/gt/2004/05/30/9Anarchists.jpg) Today marks the 32nd anniversary of the Supreme Court decision in

Today marks the 32nd anniversary of the Supreme Court decision in