Freedom Movement Celebrity Deathmatch

Here's a pretty old post from the blog archives of Geekery Today; it was written about 19 years ago, in 2006, on the World Wide Web.

A head to head on ethics and legal authority, which may be of interest in light of recent squabbles.

We're often reminded that America is a nation of immigrants, implying that we're coldhearted to restrict immigration in any way. But the new Americans reaching our shores in the late 1800s and early 1900s were legal immigrants. … We must reject amnesty for illegal immigrants in any form. We cannot continue to reward lawbreakers and expect things to get better. If we reward millions who came here illegally, surely millions more will follow suit. Ten years from now we will be in the same position, with a whole new generation of lawbreakers seeking amnesty.

Amnesty also insults legal immigrants, who face years of paperwork and long waits to earn precious American citizenship.

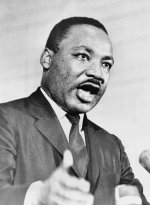

You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court's decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, it is rather strange and paradoxical to find us consciously breaking laws. One may well ask:

How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?The answer is found in the fact that there are two types of laws: There are just and there are unjust laws. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with Saint Augustine thatAn unjust law is no law at all.

Dr. King wins.

I have to say I personally disagree with King’s statement as well. King still models human ethical and political action on obedience. If you go along with a policy because it accords with you, and refuse to conform to it when it does not, then one is obeying neither one law nor the other but one’s own standards. And it is only if one’s own standards are modelled on authority, as in the case of King’s divine higher law, that this can be intelligibly called a form of obedience at all.

I’m not particularly attacking King, who obviously put this view of ethics to one of its very best uses. But I do dissent from the view of ethics involved. I would like to see us liberated not only from the state, but the ghost of the state rattling around in our heads.

King is right in principle but wrong in application.

The 1954 decision King cites wasn’t moral law, there is no moral way to administrate public schools.

(For reference, Aster makes some related points at greater length in a very good post called Rules rules rules.)

Aster,

It’s true that King was not an anarchist and his views on legal authority (probably, in part, because he views it in terms of obedience or disobedience to authority) include views that I wouldn’t subscribe to. (For example, the idea that conscientious lawbreakers are usually or maybe even always obliged to submit to the penalties for lawbreaking: Well….)

On the other hand, I’m not sure that any use of the language of (or obedience thereto) amounts to authoritarianism, or an intellectual relic of statism. I’ve made a short attempt at explaining why in this space before; Roderick added some interesting textual sources in a follow-up. GT 2005-12-15: Bill of rights day festivities also has some remarks on demythologizing the doctrine, which may be relevant. But really this deserves a post of its own to expand on the theme properly.

Roughly what I’d want to say is that talking about justice (rights, liberty, equality, etc.) sometimes merits the language of obedience to law (properly demythologized) and sometimes merits the language of autonomy, choice, values, standards, etc. (properly situated). Putting it in terms of obedience to a higher law or natural law puts you in danger of authoritarianism by suggesting an external constraint; but putting it in terms of going along with what accords with you, and refusing to conform to what does not, puts you in danger of relativism, since the phrasing raises the question of whether invasive policies might others, even though they don’t accord with you. The dialectical point that needs to be made against the danger in law-talk is that justice is not a constraint laid down on you by some outside authority; the dialectical point that needs to be made against the danger in choice-talk is that justice is not a contingent value that you can talk or leave as you see fit, but rather a categorically binding principle that’s immanent in any human form of life whatever.

Maybe the solution is to divorce the words from their unsavory connections and use each of them in their better sense; or maybe the solution is to use both provisionally, and dialectically, but to think about crafting new ways of talking, for something about justice that we are groping towards understanding, but do not yet have the words to capture.

Kennedy:

There’s no moral way to administrate government schools, but there are ways that are more immoral and ways that are less immoral. I think you can consistently hold that there’s a moral obligation for the government to desegregate government schools, so long as they exist, while also holding that the government has no right to exist or to coercively maintain schools. (Similarly, there’s no moral way to disburse tax funds other than returning them to their owners, but it’s less immoral to put them into, say, roads or useless monuments, than it is to put them into shooting innocent immigrants or drug-users.)

Of course King didn’t hold that view of government schools, but while that’s a problem with him, I don’t think that’s a reason to disagree with him that the holding in Brown expresses the moral law.

Brown is also important for having overturned the reasoning in Plessy, which protected Jim Crow statutes not only on government property, but imposed on private property against the will of the owners. Brown’s application was narrowly limited to government schools but the precedent and reasoning were then used to systematically overturn all the Jim Crow statutes that invaded private property, as well.

Kennedy and Rad Geek, I’ve got to question the logic that puts government and private management of property on wildly different moral footing. It’s immoral for the state, or a private owner, or a bunch of shareholders to run a racially segregated school. Also,

I’ve got to take issue with the idea of giving back tax money. There may well be no moral way for the State to collect and disburse taxes, but it’s much less immoral for the state to spend taxes on social programs or direct aid to the poor than to give them back to a bunch or rich people who didn’t earn them in the first place.

Labyrus,

My view is that racial segregation by private people on their own property is morally vicious, but not morally criminal. It’s appropriate to respond to it with public protest, or ostracism, but not by violent resistance. It’s only government-enforced segregation that you have a right to resist by means of force (legal or otherwise).

Government-commanded segregation is on a different moral footing from private segregation insofar as (1) it compounds the vice, by backing bigotry or cruelty with the further sin of injustice; and (2) the fact that it’s enforced immorality rather than voluntary immorality makes different means of opposition permissible.

Rad Geek, Interesting arguments, although I’m perhaps of a bit of a different perspective.

Am I correct in reading into this a definition of injustice as “immorality perpetrated by a government”, or am I oversimplifying the concept?

I am skeptical that private segretion is neccesarily voluntary for anyone involved except the property owners. If, hypothetically, a school were owned by a private school district with a policy of segregation, and the teachers all desired to desegregate their classrooms, they would have no choice, and could have their livelehoods threatened if they explored different means of opposition.

Labyrus,

I’m using here to mean a violation of individual rights, i.e., the use of force to aggress against those who are not violating anyone else’s rights. That may be committed by a government (indeed, it’s nearly all of what governments do), but it need not be. As a matter of historical fact, Jim Crow in the American South was always not only by State violence according to written legislation, but also the unwritten lynch law, violence and terror which were nominally illegal, and officially outside the auspices of the government, but practiced systematically, often openly, by both organized groups and irregular mobs, with a specific political end in mind. Segregation specifically commanded by government officials is only one example of a broader phenomenon that I’m objecting to when I talk about backing bigotry or cruelty with injustice.

In the hypothetical private school district, it is left up to the teachers’ choice whether or not to cooperate with their employer’s policy and it is left up to the students’ (or their families’) choice whether or not to attend the school. Teachers and students can (and should) refuse to cooperate with the immoral policy; a private school with a segregation policy can (and should) be protested, ridiculed, picketed, boycotted. What they can’t justly do, however, is use force to take over land or buildings owned by the private school in order for them to have desegregated classes on that property against the will of its owners.

If teachers and students want desegregated classes, they can always arrange to have the students withdraw from the school and the teacher quit to teach class for the withdrawing students. Unless they actually take such a step, they are voluntarily cooperating (no matter how grudgingly) with the immoral policies of the school. That cooperation may or may not itself be immoral (depending on the breaks), but it is voluntary (in the sense that matters for a discussion of justice) either way.