Translation of “One comrade sounds off: What’s happening now in Venezuela?” (Victor Camacho, in El Libertario)

Here's a pretty old post from the blog archives of Geekery Today; it was written about 11 years ago, in 2014, on the World Wide Web.

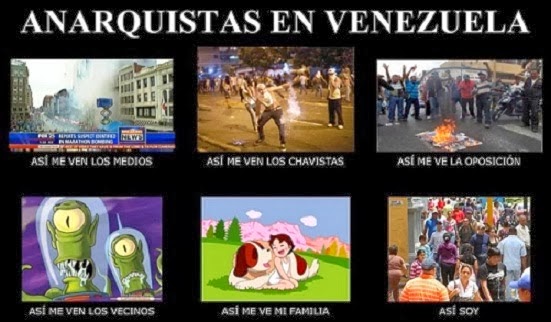

Here is another translation, this time of a commentary by the radical writer Victor Camacho, posted online as part of a series of different opinions from Venezuelan comrades by the anarchist newspaper EL LIBERT@RIO. Inline links and editorial notes in footnotes are added by me. As always, the same caveats apply: I’m a quick and nervous translator, this is a working draft, if you notice any mistakes or mangling please feel free to point them out in the comments, and I’ll attach a note or a correction to the text here. The closing note of apathy about the protest is, for what it’s worth, just one compa’s opinion; other articles from other folks at EL LIBERT@RIO have taken a range of different stances towards the protests, although all of them condemn the government’s repression of the demonstrations and the assault on civil and human rights.

Edited 23.Feb.2014. I’ve fixed three typographical errors (pointed out by Joe in comments below. –CJ

One comrade sounds off: What’s happening now in Venezuela?

Victor Camacho

Several people from outside the country have asked me about the situation in Venezuela right now. And I don’t know with scientific certainty even though I live here. But putting things in perspective, I venture to say that the great crisis in Venezuela is not a latent “coup d’etat” (as the conspiranoid government says)[1] , nor is it an economic crisis (as the opposition says), but rather an uncertainty due to the lack of elections in 2014.[2]

But first, let’s talk about context. The most remarkable, definitely, is the economic situation. Here the use of terms is interesting: for the administration, it’s a matter of “economic warfare”; for the opposition it’s a matter of an “economic crisis.” There is a shortage of basic resources, high inflation, a recently devalued currency and more forceful State intervention in the economy. The word “crisis” is intented to demonstrate the inability and the ineptitude of the government in solving those problems; the word “warfare” denotes the government’s intention to make itself out as the victim of agents who cause these problems, from without or from within. On the political side, we are facing a situation which is a very strange one for Venezuela, given that this year there will not be elections. Elections have functioned as a way of dissolving conflicts between the opposition parties and the administration, and even more, they have functioned as a factor unifying both groups: to unite against a common enemy. Thus, 2014 brings with it the risk of partisan division. Both sides, which not only have lost support but also run the risk of splitting apart, are looking ahead to a 2014 in which there is no need to keep holding themselves together. Inflation, shortages, and insecurity are conjoining factors, which function as catalysts for the political crisis, but they are not the great driving factor in this moment.

The crisis of splitting is still worse in the opposition parties. Many in the rank and file of the opposition are not content with the efforts of MUD (Mesa de la Unidad Democrática) [

Board of Democratic Unity] or of Capriles, these would be above all the most radical opposition figures. they are not content with the recent pact between the leaders of the opposition, which has tacitly accepted the Maduro government to work together with the government on many different projects, among them the issue of insecurity. In fact, the larger part of the leadership of MUD is not promoting the protests. Thus, Leopoldo L?@c3;b3;pez and María Corina Machado, also former candidates for the presidency, are exploiting this rank-and-file discontent in the opposition in order to steal the show.[3] Many in the opposition are really bothered by the current situation and waited very eagerly for the call to get out into the streets, which is why Leopoldo L?@c3;b3;pez is the name most discussed these days to be the one who expresses many of their sentiments, while the popularity of Capriles decays. Ironically, the reasons for the protest are vague enough and there is no unified criterion: not everyone protests for the same reason, whether it be for the detained students, the economic situation, the insecurity, all of the above or something else that escapes me.On the government’s side, more than anything, there’s rejoicing. Opposition radicalism benefits Chavismo a lot, because if Chavismo knows how to do anything, it’s uniting in the face of adversity. The protests help the government to demonstrate that the opposition is violent and outside of the law. They serve to create a scenario where the State is the victim of a common enemy, that there is no time for internal discussions within the Chavista movement, because better us than them. The government signals that there is an environment of protest similar to the one on April 11, 2002,[4] as if there were a coup d’etat lying hidden in these protests, but even though the environment is tense enough like in 2002, and one of the demands is the immediate resignation of the president, there is no likely terrain for a coup d’etat. The opposition hasn’t got one bit of control in the Armed Forces; nor in any other public force; the opposition has only two governors, and, also, their leaders are negotiating with the government. It is hardly likely that a coup d’etat could happen, and, for it to happen, this could only come from high places in the same government.

It is difficult to know exactly what is happening in the country, given that there is an information barrier imposed by the government. One of the factors that caused the protests to spring up is printed media’s lack of acccess to paper, what it costs to start up many newspapers with national or local circulation, including communal and worker-run media.[5] On national television, they are not showing the protests that are happening in the country, and when it happens it is only to show the acts of vandalism and violence in which protesters are involved. The government’s imposition on audiovisual media has been so constant that self-censorship is the norm. In this way, civil society jumps over the information-wall through the use of social networks, especially Twitter. But also this has not been perfect; on the one hand there have been accusations of censorship of connections to the social network Twitter by the State telecommunications company, CANTV, which offers approximately 90% of the Internet connections; and, on the other hand there have been accusations from the government of the use of social networks to spread false information, above all of images of supposed repressions of protests. The information has been used as a matter of convenience for both sides, for example, the administration typically only gives importance to the death of one pro-government demonstrator,[6] forgetting the other 2 deaths in the opposition; while the opposition is accustomed to forget the death of the pro-government demonstrator while crying over the death of the 2 opposition members. In this sense, the political repression and the para-policing groups are no “fairy tale” as the government tries to insist. The police have used firearms against the protesters and what the police cannot do (tortures and intimidation, for example) is done by so-called “colectivos,” armed groups which function as para-police corps.

In my opinion, these protests benefit only the government, and the only good thing that they offer to the opposition is to free the rage that they are keeping inside. Keep in mind, I’ll remind you, I don’t identify with either side. Beyond that, I can’t add any more.

— Opina un compa: ¿Qué pasa ahora en Venezuela? (February 22, 2014). Translated by Charles W. Johnson.

- [1]Original Spanish:

conspiranoia,

a play onconspiraci?@c3;b3;n

andparanoia.

↩ - [2]He doesn’t mean that elections have been suspended; it’s due to coincidences in the normal scheduling of elections. Presidential elections in Venezuela are held every six years, with the most recent election in 2013. Parliamentary elections are held every five years, with the most recent election in 2010. Regional elections are held every four years, with the most recent election in 2012. As a result it’s common to have many election years in a row, but as it happens there are no regular elections scheduled for 2014. –CJ↩

- [3]

para robar el protagonismo

↩ - [4]The date of the U.S.-backed coup attempt against Hugo Chavez in 2002↩

- [5]

medios comunitarios y autogestionados↩

- [6]Original Spanish:

el oficialismo s?@c3;b3;lo suele dar importancia a la muerte de un oficialista.

↩

Some “quick and nervous” typos:

leaders of hte opposition

supposed repssions of protests

para-policing groups are not are no “fairy tale”

As an aside, there is an interesting contrast between the typical Latin American expression of “the government of Maduro” (or whomever) vs. the U.S. expression (or should I say euphemism?) of “the Obama (or whomever) administration”. The latter sounds benign as simply a temporary group, trying to manage things for everyone’s benefit, whereas the former recognizes the ruling intent.

Thanks! Typos should be fixed.

I think you’re right about the euphemism of The USAmerican usage is certainly atypical — it’s common enough in other English-speaking countries to talk about, e.g., the or the etc. I’d actually be kind of curious to know when the U.S. practice started — whether that’s always been the way that presidential regimes have been referred to, or whether it started at some particular point in the U.S.’s political history. (There are contemporary books which were written specifically about Lincoln, and even of Franklin Pierce, so it seems to be antebellum and not a very recent development, but I don’t know whether it goes back further than that or not.)