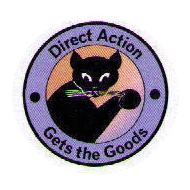

Direct action gets the goods

(Via William Gillis 2009-04-22.)

I’ve never given much of a damn about how many NLRB rulings the Wobbly baristas at Starbucks might be able to win; or about conventional labor politics like the debate among labor bosses and corporate bosses over card-check procedures for NLRB recognition. The reason I haven’t given much of a damn is that those sorts of things aren’t worth it. The NLRB is a rigged game, and a tool of the corporate State; it uses superficial privileges, illusory benefits, and the most rigid sort of regimentation to domesticate the labor movement, and to bury any potential for dynamism or for radical socio-economic change under red tape, paperwork, and politically-controlled rules of engagement. That sort of thing it is, increasingly, demonstrably ineffective; it’s also authoritarian, and ultimately founded on coercion. But, also, that shit is just boring. Why waste your damns on that sort of thing, when there are things like this to give a damn about — solidarity expressed through free market action, and fight-to-win unionism carried out through free association on the shopfloor, without the permission of bosses or bureaucrats:

WORKER DISCONTENT over Starbucks’ pay and conditions set the stage for organizing. In May 2004, workers at a midtown Manhattan Starbucks launched the SWU.

From the beginning, the company went all out to bust the union.

We wanted to negotiate with Starbucks over our serious concerns,[Starbucks Workers’ Union organizer Erik] Forman recalled.But rather than sit down at a table with us, the bosses began writing checks to the union-busting consultants of Akin Gump and the PR flacks at Edelman, the world’s largest public relations firm. They contracted Edelman to craft a facade ofsocial responsibility.At first, workers filed for a NLRB election to vote on union recognition. Starbucks responded by

using its political clout to gerrymander the bargaining unit from one pro-union store to every store in midtown and downtown Manhattan,Foreman said.The workers realized they couldn’t win, so they tried a different tack. Unable to go the traditional route to unionization via an NLRB election, they drew on more radical traditions–fighting back around wages, benefits and working conditions and recruiting baristas to the union without official NLRB recognition. As Forman says:

We’ve decided to go back to the basics of the labor movement. Workers organized unions before 1935, before we had a

rightto organize…In developing an organizing model that works in the service industry, we’ve gone back to the roots of unionism, opting for a strategy that putsdirect actionat the center. We’ve been able to spread because we’ve done something that business unions would consider unthinkable–we’ve put our organization entirely in the hands of rank-and-file baristas.Forman said that the SWU emphasizes what it calls

solidarity unionism–that is, the idea thatworkers are most powerful where the bosses need us most: on the shop floor. Our power as workers comes from our ability to withhold our labor, or interfere with the production process in other ways.At the Mall of America last summer, workers confronted management about unbearable temperatures in the store. As Forman described it:

We had been complaining about how hot it was for years, but management refused to buy a fan or install air conditioning because it was

too expensive.At the same time, our store was pulling in $30,000 a week.One morning, four of my coworkers walked into the back room of our store and gave the boss an ultimatum:

Will you buy the store a fan? Yes or no?He stalled….so my four coworkers walked off the job, got in a car and drove to Target, leaving the boss to cover the floor. He was livid.About 20 minutes later, my coworkers walked back in with a $14 box fan. They plugged it in, wrote

Courtesy of the IWW,drew a small blackSabotage cat[the IWW logo] on it, and enjoyed the breeze.This left management with a choice. They could either remove the fan, in which case they would look like jerks. Or they could leave it there, as a monument to their own negligence.

To their credit, they did the right thing. Two days later, the district manager arrived with a $150 industrial floor fan. Two weeks later, they began installing air conditioning. This is the power of direct action. One week, $40 is too much to spend to bring the temperature in the store to within OSHA standards. The next week, management is spending $10,000 to keep the workers happy.

— Adam Turl, SocialistWorker.org (2009-04-17): Standing up to Starbucks

Direct action gets the goods.