Free The Unions (and all political prisoners)

Today is May Day, or International Worker’s Day: an international day for celebrating the achievements of workers and the struggle for organized labor.

You might have thought that the proper day was Labor Day,

as traditionally celebrated on the first Monday in September. Not so; the federal holiday known as Labor Day

is actually a Gilded Age bait-and-switch from 1894. It was crafted and promoted in an effort to throw a bone to labor

while erasing the radicalism implicit in May Day (a holiday declared by workers, in honor of the campaign for the eight hour day and in memory of the Haymarket martyrs). As a low-calorie substitute for workers’ struggle to come into their own, we get a celebration of labor

… so long as it rigidly adheres to the AFL-line orthodoxy of collective bargaining, appeasement, and power to the union bosses and government bureaucrats. That this holiday emerged and solidified at exactly the same historical moment as the unholy alliance of conservative (statist, nativist, racist, and misogynist) unionism with corporate barons and the Progressive

regulation movement is no coincidence. That AFL-line unions continue to use Labor Day as a chance to co-opt the historic successes of radical, libertarian unions in campaigns such as the fight for the eight-hour day or the five-day week is no coincidence, either.

Too many of my comrades on the Left fall into the trap of taking the Labor Day version of history for granted: modern unions are trumpeted as the main channel for the voice of workers; the institutionalization of the system through the Wagner Act and the National Labor Relations Board in 1935, and the ensuing spike in union membership during the New Deal period, are regarded as one of the great triumphs for workers of the past century.

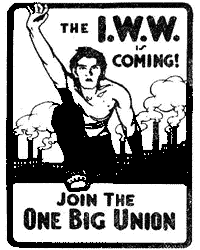

You may not be surprised to find out that I don’t find this picture of history entirely persuasive. The Wagner Act was the capstone of years of government promotion of conservative, AFL-line unions in order to subvert the organizing efforts of decentralized, uncompromising, radical unions such as the IWW and to avoid the previous year’s tumultuous general strikes in San Francisco, Toledo, and Minneapolis. The labor movement as we know it today was created by government bureaucrats who effectively created a massive subsidy program for conservative unions which followed the AFL and CIO models of organizing–which emphatically did not include general strikes or demands for worker ownership of firms. Once the NRLB-recognized unions had swept over the workforce and co-opted most of the movement for organized labor, the second blow of the one-two punch fell: government benefits always mean government strings attached, and in this case it was the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which pulled the activities of the recognized unions firmly into the regulatory grip of the federal government. Both the internal culture of post-Wagner mainstream unions, and the external controls of the federal labor regulatory apparatus, have dramatically hamstrung the labor movement for the past half-century. Union methods are legally restricted to collective bargaining and limited strikes (which cannot legally be expanded to secondary strikes, and which can be, and have been, broken by arbitrary fiat of the President). Union hiring halls are banned. Union resources have been systematically sapped by banning closed shop contracts, and encouraging states to ban union shop contracts–thus forcing unions to represent free-riding employees who do not join them and do not contribute dues. Union demands are effectively constrained to modest (and easily revoked) improvements in wages and conditions. And, since modern unions can do so little to achieve their professed goals, and since their professed goals have been substantially lowered anyway, unionization of the workforce continues its decades-long slide.

May Day is a celebration of the original conception of the labor movement, as expressed by anarchist organizers such as Albert Parsons, Lucy Parsons, Benjamin Tucker, and others: a movement for workers to come into their own, by banding together, supporting one another, and taking direct action in the form of boycotts, work stoppages, general strikes, and the creation of workers’ spaces such as local co-operatives and union hiring halls. The spirit was best expressed by John Brill’s famous exhortation to Dump the bosses off your back

–by which he did not mean to go to a government mediator and get them to make the boss sit down with you and work out a slightly more beneficial arrangement. Dump the bosses off your back!

meant: organize and create local institutions that let you bypass the bosses. Negotiate with them if it’ll do some good; ignore them if it won’t. The signal achievements of the labor movement in the late 19th and early 20th century were achievements in this spirit: the campaigns that won the 8 hour day and the weekend off in many workplaces, for example, emerged from a unilateral work stoppage by rank-and-file workers, declared by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, and organized especially by the explicitly anarchist International Working People’s Association, after legislative efforts by the National Labor Union and the Knights of Labor failed. The stagnant, or even backsliding, state of organized labor over the past half century is the direct result of government colonization and the ascendency of government-subsidized unions.

Don’t get me wrong: the modern labor movement, for all its flaws and limitations, is the reflection (no matter how distorted) of an honorable effort; it deserves our support and does some good. Union bosses, corporate bosses, and government bureaucrats may work to co-opt organized labor to their own ends, but rank-and-file workers have perfectly good reasons to support AFL-style union organizing: modern unions may not be accountable enough to rank-and-file workers, but they are more accountable than corporate bureaucracy; modern unions bosses don’t care enough about giving workers direct control in their own workplace, but they care more than corporate bosses, who make most of their living by denying workers such control. The labor movement, like all too many other honorable movements for social justice in the 20th century, has become a prisoner of politics: a political situation has been created in which the most rational thing for most workers to do is to muddle through with a co-opted and carefully regulated labor movement that helps them in some ways but undermines their long-term prospects. It doesn’t make sense to respond to a situation like that with blanket denunciations of organized labor; the best thing to do is to support our fellow workers within the labor movement as it is constrained today, but also to work to change the political situation that constrains it, and to set it free. That means loosening the ties that bind the union bosses to the corporate and government bureaucrats, by working to repeal the Taft-Hartley Act, and abolish the apparatus of the NLRB, and working to build free, vibrant, militant unions once again.

Dump the bosses off your back. Free the unions, and all political prisoners!

Update (2007-04-19): For a long time this post incorrectly attributed the song Dump the Bosses Off Your Back

to Joe Hill, the legendary songwriter and organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World. Although it is very similar in style to Hill’s songs — it sets a radical message in simple language to the melody to a popular hymn — the song was actually written by John Brill, another Wobbly songwriter. The song first appeared in the Joe Hill Memorial (9th) edition of the IWW songbook, released in March 1916, four months after Joe Hill was hanged by the state of Utah. This error has been corrected in the post. –CJ