Translation of Report from San Cristobal, Tachira (Anonymous, reprinted by El Libertario)

Here is another report from the streets in Venezuela, posted online by the Venezuelan anarchist paper EL LIBERT@RIO. Inline links and editorial notes in footnotes are added by me. The same caveats apply as elsewhere; if you notice any mistakes or mangling please feel free to point them out in the comments, and I’ll attach a note or a correction to the text here.

Report from San Crist?@c3;b3;bal, Táchira, 19-February-2014

Anonymous

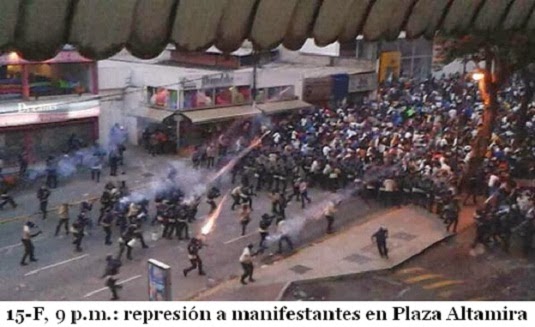

This morning the sun rose on San Crist?@c3;b3;bal desolated by the bloody attack perpetrated by the Bolivarian National Guard against students who were posted at the intersection of Avenida Carabobo with Ferrero Tamayo. The deployment was striking and devastating: birdshot,[1] expired gas cannisters,[2] tear-gas bombs, stun grenades, and a contingent of the motorized brigade of the military corps that was escorting a tank and two armored vehicles that trashed the tactical reserves of the students.

In spite of such a bloody attack the boys battled them for a space of hours, until fatigue put a dent in them, due to the orchestrated plan of attack; after razing the place, the troops kept on with their devastating frenzy, completely destroying the barricades set up by the active citizenry, who kept a vigil until late into the night. Neighbors from various streets of Barrio Obrero, La Romera, La Avenida Carabobo, Avenida Ferrero Tamayo and the whole high part of the city, are witnesses to what I'm saying.

It is important to highlight that in addition to the Bolivarian National Guard, groups of gunmen on motorcycle were encountered, who intermittently attacked different parts of the city, returning to the outside of the state capitol to refill their ammunition and fuel for their motorcycles after carrying out the raids on the sites previously analyzed.

As if all that weren't enough, the same commando group that attacked the students, posted in the site previously mentioned, set off for the vicinity of Táriba, where, revealing all their training in military tactics, they mounted a frontal attack, without any pity, on the collectivity; due to the brutality of the attack, over there the actions were much quicker. Next they headed over to retake control of the bridge of Las Vegas de Táriba, an important access point that allows a connection by ground with the plains. Once again the Bolivarian National Guard showed their worst face, and used everything to attack those who protested in the zone. It's noteworthy that the neighbors in the Conjunto Residencial Don Luis (a group of buildings) were affected by the effects of the different gasses that were thrown without any coherent reason into the middle of that town.

The city revealed its worst face; they were breathing air loaded with a fetid stench and the smell of burning rubber and plastic. Public transit was paralyzed in 99% of the city, rising to 100% before eight in the morning; the barricades showed up in every part of San Crist?@c3;b3;bal, some upright and steady, others partly standing, and some completely collapsed, the community has reflected its powerlessness in the asphalt that has served as a blackboard for messages of "SOS" and "HELP."

The thing that San Crist?@c3;b3;bal has lived through is without precedent, a hostile situation, which the armed "collectives" have exploited to rob, destroy and attack those who were obliged to stay at the few workplaces that can still be found open. Speaking of business, shops have closed for the day, the street vendors have disappeared completely from the streets, the only places that have opened their doors are some supermarkets and public markets, which were motivated by pressure from different government authorities, which threaten them with fines and additional legal actions.

At this time (6:30pm) the fuse of protest has been lit once again. I'm informed that encounters with National Guard troops in the high part of the city, and neighbors and organized civil society have appeared strongly resisting the attacks of the Bolivarian National Guard, which is making use of aerial tactics through the use of Mi-17V-5 helicopters, one of the latest assault and transport models of the legendary Russian helicopter, purchased by the Venezuelan government, which in addition to flying over and reporting is also conducting airlifts between the Buenaventura Vivas base in Santo Domingo and the airport in Paramillo.

–Translation of Reporte desde San Crist?@c3;b3;bal, Edo. Táchira, 19/02/2014 by An?@c3;b3;nim@. Translated by Charles W. Johnson.

- [1]Perdigones, pellets. The Bolivarian National Guard frequently uses small-gauge shotgun fire as a crowd-control weapon.↩

- [2]Expired tear-gas cannisters were frequently used against Egyptian protesters in Tahrir Square, leading to some claims that the expired cannisters might cause more dangerous reactions in people exposed to the gas. The idea is not widely supported by scientists, but the accusation that expired cannisters are being used in Venezuela has led to an investigation.↩