Republican virtue (or: the Man who would be King)

Here's a pretty old post from the blog archives of Geekery Today; it was written about 19 years ago, in 2006, on the World Wide Web.

Back around Presidents’ Day, David Boaz sent a communique out from Planet CATO in praise of George Washington, consisting mainly of a panegyric on G.W.’s lived example of republican virtue. We begin with the headline The Man Who Would Not Be King

and move on through some of the favorite tropes of nationalist nostalgia for the Old Republic:

George Washington was the man who established the American republic. He led the revolutionary army against the British Empire, he served as the first president, and most importantly he stepped down from power.

In an era of brilliant men, Washington was not the deepest thinker. He never wrote a book or even a long essay, unlike George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams. But Washington made the ideas of the American founding real. He incarnated liberal and republican ideas in his own person, and he gave them effect through the Revolution, the Constitution, his successful presidency, and his departure from office.

What's so great about leaving office? Surely it matters more what a president does in office. But think about other great military commanders and revolutionary leaders before and after Washington–Caesar, Cromwell, Napoleon, Lenin. They all seized the power they had won and held it until death or military defeat.

… From his republican values Washington derived his abhorrence of kingship, even for himself. The writer Garry Wills called him "a virtuoso of resignations." He gave up power not once but twice — at the end of the revolutionary war, when he resigned his military commission and returned to Mount Vernon, and again at the end of his second term as president, when he refused entreaties to seek a third term. In doing so, he set a standard for American presidents that lasted until the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose taste for power was stronger than the 150 years of precedent set by Washington.

And what did Washington do when, out of his abhorrence of kingship, even for himself,

he stepped down and returned home? Here’s the way Boaz puts it:

Master George, farming

What values did Washington's character express? He was a farmer, a businessman, an enthusiast for commerce. As a man of the Enlightenment, he was deeply interested in scientific farming. His letters on running Mount Vernon are longer than letters on running the government. (Of course, in 1795 more people worked at Mount Vernon than in the entire executive branch of the federal government.)

Ah, yes, his farming,

with his numerous workers

at Mount Vernon.

You see, the thing about Washington is that while he was busy Not Being a King by returning to

You see, the thing about Washington is that while he was busy Not Being a King by returning to farm

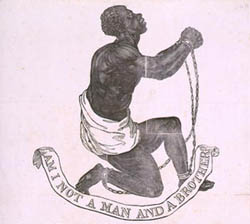

at Mount Vernon, he was personally claiming the authority to rule as Lord and Master over several hundred of his fellow human-beings, held as chattel slaves, with more absolute and invasive authority over his subjects than any Bonaparte ever even dreamed of exercising over the common men and women of France. As the landed lord of one of Virginia’s largest slave-plantations he demanded absolute control over their conduct, took every last penny earned by their labor, and reserved the right to exercise almost any physical brutality that he saw fit to inflict in order to punish or deter challenges to his authority. (And that is, note, not a matter of whether or not he actually acted unusually harshly towards any given slave; it’s part and parcel of what being a grand Virginia slave-lord meant.) The Man Who Would Not Be King

arrogantly claimed for himself rights and prerogatives that merely political tyrants would have trembled to assert, solely on the basis of his money and his position within the racial aristocracy of the American South.

Washington was certainly an interesting character; studying his life may even have some things to teach us. But sentimental lies have nothing to teach us at all, and the ridiculous notion that Washington, the slave-driver of hundreds, abhorred tyranny or arbitrary power is nothing more or less than a sentimental lie. He may very well have abhorred the idea of ruling over fellow white people; he may very well have disliked crowns and robes as a point of fashion; but he had no problem maintaining absolute tyranny over hundreds of blacks, spanning his life from the age of 11 until his death. And if you think that’s good enough to count as exemplifying republican virtue, as abhorring kingship, or as retiring from a seat of power to a private life, then you need to think a lot harder.

Of course most of the Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson for instance, owned slaves and defended slavery — so what? Sure Boaz distorted the reality toward the end of the piece. That doesn’t change the fact that the Fathers appreciated liberty much more than a lot of people living at that time. If you’re going to criticize someone at least do it with a modicum of proportion.

He did abhor tyranny. Like most men of the time period, however, he was inconsistent in applying his abhorrence of tyranny. You, however, portray him primarily as dedicated to enslavement, and this sounds like wishful thinking on your part. When analyzing historical figures try to be cognizant of “blacks” AND “whites” (ha!), since most people are a shade of gray.

For the record, I would apply and have applied exactly the same judgment to other slaver Founders, such as Thomas Jefferson or Patrick Henry. I admire the Declaration of Independence (to take one example) quite a bit; Jefferson — a slaver, rapist, scoundrel, and posturing hypocrite — very little. So, whether I’m right or wrong, invoking Jefferson and the rest of the gang is not going to sway me very much here.

Now, on to Washington:

Virtue is a matter of what kind of person you are, not a matter of how you stack up in a competition with your neighbors. And demanding the power of imperium over several hundreds of your fellow people is a very serious vice. In particular, it’s a vice that’s inconsistent with any claim to abhor tyranny or kingship, because it involves claiming all the powers and prerogatives of life-long absolute monarchy over your unwilling subjects. In the mouths of slaveholders, panegyrics to liberty and to republican virtue, or polemics against kings and tyrants, are empty lies.

That doesn’t mean that we can’t put their words in our mouths and make them mean something real (Garrison, Douglass, and many other abolitionists did just that). But it does mean that we have to rethink what we are going to say about the men who penned the words.

means treating things according to the size and significance that they in fact had. But personally holding hundreds of your fellow people as chattel slaves is not a minor failing or a foible of fallen creatures. It is an atrocity of the first order, and the specific nature of the crime is exactly the same as that committed by every power-lusting Hapsburg or Bourbon or Bonaparte in history. Except that the crimes of slave-holders were worse; they routinely involved powers and prerogatives to confine, hurt, and feed off of people in ways more systematic, invasive, and intense than any crowned head of Europe ever dreamed of claiming over ordinary subjects.

The upshot is that I would like to suggest that a sense of requires taking the tyranny exerted by the slave-lords of the South every bit as seriously as crimes inflicted against, y’know, white people. A sense of proportion also demands that we pay attention to how much of his life Washington spent destroying and feeding off of the lives of his unwilling subjects at Mount Vernon; that is every bit as political and every bit as serious a matter as his 8 years as a general and his 8 years in the Presidency; and in point of fact, he spent much longer on the former than on the latter.

This is the same thing as saying that he abhorred tyranny only in some cases and not in others; and in particular, that while he may have disliked tyranny over white people, he had no real problem with tyranny over black people. In point of fact, pointing — as Boaz does — to his devotion to his plantation and his enthusiasm for (which required much more systematic and invasive slave-driving as an essential part of the program) illustrates how much emphasis he put on tyrannizing and robbing from black people — which is all that his amounts to — in his own life.

It’s not as if Washington were so busy abhorring tyranny over white people that he just forgot somehow to his hatred to tyranny over black people. He and most of the other Founders were acutely aware of the fact that they were suggesting different standards for black people than they were for white people, and even if they had been too stupid to see it, contemporary critics such as Samuel Johnson pointed it out clearly to them (). Different yelping slavers acted on it in different ways; Jefferson and Patrick Henry by wringing their hands and doing nothing about it; Washington by doing nothing about it for most of his life, trading in slaves to increase his manor, quietly endorsing racist colonization schemes while publicly opposing Quaker abolitionists later in his life, and providing in his will for the gradual manumission of the slaves held under his name after both his death and Martha’s. (A plan that not only ensured his own life-long tyranny over the enslaved, but also put Martha’s life at considerable risk after he died.) In other words, he was well aware of the problem, and he just did not care enough about black people’s lives or freedoms to do something effectual, public, or immediate about it.

I’m not suggesting that there is nothing to learn from Washington’s example or that he never did anything admirable. What I am suggesting is that there’s nothing to learn from sentimental lies, and that a proper sense of proportion demands that we take Washington’s slaveholding into account. Which neither Boaz nor most other white people indulging in this kind of sentimental Old Republic nationalism happen to do.

Incidentally, both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr were comparatively good on the slavery question.

As an example both of Jefferson’s virtues as a theorist and of his hypocrisy as an individual, see the first draft of the Declaration of Independence, where he condemns slavery — but blames it on the King of England:

Well, thank goodness the American Revolution put an end to that unpleasantness.

Incidentally, I wonder what we are to make of the old Icelandic Commonwealth, which, in some respects, appears to have been an unusually libertarian society in some respects, but which was also a slave society. It seems bitterly ironic that Iceland abandoned slavery only under the influence of Christianity, which also lead to the eventual collapse of the Commonwealth.

It seems that “liberty” is a concept which people have found easy — or, at least, feasible — to compartmentalise, enthusing over it for the in-group, but steadfastly denying it to others.

It’s certainly true that “compartmentalisation” is all too common. But slavery does seem to have been dying out in Iceland even prior to the Christian “conversion” — not out of any moral enlightenment, however, but because the ecology of Iceland necessitated a shift in emphasis from agriculture to pasturing, which requires a higher degree of unsupervised labour, making slavery less viable.

It’s also worth noting that Icelandic slavery, though certainly evil as all slavery is, did not represent anything like the degree of oppresison and brutalisation that antebellum American slavery did. (For example, in Iceland slaves could own private property, which slaveowners could not use without the slave’s permission.)

Another thought: while I agree that slaveowners in the past deserve moral condemnation, it doesn’t follow that most people nowadays are to be congratulated for their moral superiority over these past slaveowners. For all too many people nowadays, I fear, are anti-slavery for the same reason that their ancestors were pro-slavery: because they’ve passively absorbed the values of their culture. (The irrepressible Richard Mitchell makes this point in his marvelous essay The Land of We All.)

The interesting question is: how many (white) people today who are anti-slavery would still have been anti-slavery if they’d been born in antebellum Virginia? There’s no easy way to test this, but one clue is in the attitude they take toward widely accepted injustices today. If they passively accept present-day injustice, the likelihood that they would have rebelled against equally widely accepted injustices 200 years ago is slight. (Of course the — perhaps suspiciously? but nonetheless reassuringly — self-congratulatory moral is that we today who are anarchists, feminists, antimilitarists, etc., can plausibly claim that we would have been abolitionists back in the day!)

And even that is, as you say, no real way of telling. Which is why I strongly dislike self-righteousness about people in the past–it smacks of that smug assumption that we would all be Huck Finn, that we would all be the Good White Guy who disapproves of lynching or the Good Man who never beats or rapes his wife. And let’s face it, most of us wouldn’t be.

Was Washington’s slave-owning evil? Fuck, yes. But it was also affected by his culture and the dominant beliefs of his time. Culture affects actions. We don’t live in a vacuum, and while this doesn’t absolve the slaveowners, it mitigates their circumstances. We, at any rate, hve no right to get complacent about ourselves in relation to them.