May Day 2007

Here's a pretty old post from the blog archives of Geekery Today; it was written about 18 years ago, in 2007, on the World Wide Web.

We Have Fed You All for a Thousand Years

We have fed you all for a thousand years,

And you hail us still unfed,

Though there’s never a dollar of all your wealth

But marks the workers dead.

We have yielded our best to give you rest,

And you lie on crimson wool;

But if blood be the price of all your wealth

Good God we have paid in full.There is never a mine blown skyward now

But we’re buried alive for you;

There’s never a wreck drifts shoreward now

But we are its ghastly crew.

Go and reckon our dead by the forges red,

And the factories where we spin;

If blood be the price of your cursèd wealth

Good God we have paid it in.We have fed you all for a thousand years–

For that was our doom, you know,

From the days when you chained us in your fields

To the strike a week ago.

You have taken our lives, and our husbands and wives,

And called it your legal share;

But if blood be the price of your lawful wealth

Good God we bought it fair.–First printed by the Industrial Workers of the World in 1908. Words by

an anonymous proletarian,tune by Rudolph von Leibich

Fellow workers:

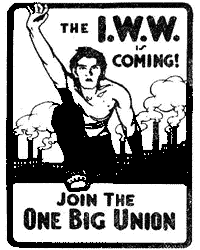

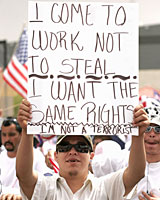

Today is May Day, or International Workers Day, a holiday created by Chicago workers–most of them anarchists–to honor the memory of the Haymarket martyrs and to celebrate the struggle of workers for freedom, a better life, and determination of the conditions of their own labor. It’s also the second annual day of strikes and marches for immigrant workers’ rights. May Day is and ought to be a day of resistance against the arrogance and power of the plutocrats. A day to celebrate workers’ struggles for dignity, and for freedom, through organizing in their own self-interest, through agitating and exhorting for solidarity, and through free acts of worker-led direct action to achieve their goals, marching under the banners of We are all leaders here

and Dump the bosses off your back

. A day to cheer immigrant workers struggling for their own freedom, in defiance of the attempts by La Migra and freelance nativist bullies to silence and intimidate them, marching under the banners We are not criminals,

and We are not going anywhere.

A day to remember:

There Is Power In A Union

There is power, there is power,

In a band of working folk,

When we stand

Hand in hand.–Joe Hill (1913)

In honor of the day, it’s a pleasure to recommend some reading from anti-state radicals–from a history of May Day’s American roots at The Agitator (Lauritz, not Balko), to Kevin Carson’s Organized Capital vs. Organized Labor, to Sheldon Richman’s column Labor’s Right to a Free Market. And I’d especially like to recommend Kevin’s simply brilliant earlier column, The Ethics of Labor Struggle: A Free Market Perspective. Kevin’s and Sheldon’s columns do an especially good job of showing the gulf between the managerial style of establishmentarian business unionism–so familiar to us in these the waning days of Babylon, with Wagner and Taft-Hartley carefully arranged to bring the established unions into the web of State privilege and State regulation–with the older, state-free tradition of wildcat unionism that May Day celebrates. Here’s Kevin Carson:

First of all, when the strike was chosen as a weapon, it relied more on the threat of imposing costs on the employer than on the forcible exclusion of scabs. You wouldn’t think it so hard for the Misoids to understand that the replacement of a major portion of the workforce, especially when the supply of replacement workers is limited by moral sympathy with the strike, might entail considerable transaction costs and disruption of production. The idiosyncratic knowledge of the existing workforce, the time and cost of bringing replacement workers to an equivalent level of productivity, and the damage short-term disruption of production may do to customer relations, together constitute a rent that invests the threat of walking out with a considerable deterrent value. And the cost and disruption is greatly intensified when the strike is backed by sympathy strikes at other stages of production. Wagner and Taft-Hartley greatly reduced the effectiveness of strikes at individual plants by transforming them into declared wars fought by Queensbury rules, and likewise reduced their effectiveness by prohibiting the coordination of actions across multiple plants or industries. Taft-Hartley’s cooling off periods, in addition, gave employers time to prepare ahead of time for such disruptions and greatly reduced the informational rents embodied in the training of the existing workforce. Were not such restrictions in place, today’s “just-in-time” economy would likely be far more vulnerable to such disruption than that of the 1930s.

More importantly, though, unionism was historically less about strikes or excluding non-union workers from the workplace than about what workers did inside the workplace to strengthen their bargaining power against the boss.

The Wagner Act, along with the rest of the corporate liberal legal regime, had as its central goal the redirection of labor resistance away from the successful asymmetric warfare model, toward a formalized, bureaucratic system centered on labor contracts enforced by the state and the union hierarchies.

…

It’s time to take up Sweeney’s half-hearted suggestion, not just as a throwaway line, but as a challenge to the bosses. We’ll gladly forego legal protections against punitive firing of union organizers, and federal certification of unions, if you’ll forego the court injunctions and cooling-off periods and arbitration. We’ll leave you free to fire organizers at will, to bring back the yellow dog contract, if you leave us free to engage in sympathy and boycott strikes all the way up and down the production chain, boycott retailers, and strike against the hauling of scab cargo, etc., effectively turning every strike into a general strike. We give up Wagner (such as it is), and you give up Taft-Hartley and the Railway Labor Relations Act. And then we’ll mop the floor with your ass.

— Kevin Carson, The Ethics of Labor Struggle: A Free Market Perspective

That’s just a sampling. You really must read the whole thing.

Meanwhile, in the news, some creep in Washington is wandering around proclaiming Loyalty Day

and demanding our renewed allegiance; and while the punch-drunk official unions are begging the government for more favors, the captains of industry are begging the government to keep a tight leash on free association. But the most significant events for labor and for human freedom are happening beyond the noise and spectacle of that gladiatorial arena, in the streets of cities all over the country where workers demand their rights in defiance of the so-called immigration law, and in unrecognized, grassroots unions organized along syndicalist lines, where workers have won concrete gains from the biggest corporations in their industry by operating through the use of creative secondary boycotts. There is a lesson here–a lesson for workers, for organizers, for agitators, and anti-statists. One we’d do well to remember when confronted by any of the bosses–whether corporate bosses or political, the labor fakirs and the authoritarian thugs styling themselves the vanguard of the working class, the regulators and the deporters and the patronizing friends of labor

all:

Dump the Bosses Off Your Back

Are you cold, forelorn, and hungry?

Are there lots of things you lack?

Is your life made up of misery?

Then dump the bosses off your back!–John Brill (1916)

Thanks for the link, Charles. Glad to see the Wobbly lyrics–especially serendipitous seeing it just now, considering I ordered Utah Phillips’ “We Have Fed You All For a Thousand Years” album this morning.

Same for me, Charles. Thanks! We’ll broaden the perspective of the libertarian movement yet!

I’ve seen those lyrics attributed to Rudyard Kipling, of all people. I rather doubt the attribution is accurate, but it’s odd enough that I’ll mention it anyway…

Kevin:

What a great album. I’m also a huge fan of his collaboration with Ani DiFranco, Fellow Workers.

Jesse:

Kipling didn’t write the lyrics, but he did write a poem (about common sailors) that the anonymous Wobbly songwriter was very clearly cribbing from, which is where the attribution probably came from. Cf. the second section of Song of the Dead, from The Seven Seas (1896). Like all the great Wobbly songs, We Have Fed You All For A Thousand Years drew from the popular melodies and lyrics in its cultural environment and adapted them to the Wobs’ own purposes (although drawing from Kipling was a bit unusual; most often they picked up on old hymn tunes.)

Thanks, Charles — that makes sense.