Written in 2006, published in print in 2008.

The purpose of this essay is political revolution. And I don’t mean a

"revolution" in libertarian political theory, or a revolutionary new political

strategy, or the kind of "revolution" that consists in electing a cadre of new

and better politicians to the existing seats of power. When I say a

"revolution," I mean the real thing: I hope that this essay will contribute to

the overthrow of the United States government, and indeed all governments

everywhere in the world. You might think that the argument of an academic essay

is a pretty slender reed to lean on; but then, every revolution has to start

somewhere, and in any case what I have in mind may be somewhat

different from what you imagine. For now, it will be enough to say that I intend

to give you some reasons to become an individualist anarchist,[] and undermine some of the

arguments for preferring minimalist government to anarchy. In the process, I

will argue that the form of anarchism I defend is best understood from what

Chris Sciabarra has described as a dialectical orientation in social

theory,[] as part of a larger effort to

understand and to challenge interlocking, mutually reinforcing systems of

oppression, of which statism is an integral part—but only one part among others.

Not only is libertarianism part of a radical politics of human liberation, it is

in fact the natural companion of revolutionary Leftism and radical feminism.

My argument will take a whole theory of justice—libertarian rights

theory[]—more or less for granted: that is, some

version of the "non-aggression principle" and the conception of "negative"

rights that it entails. Also that a particular method for moral inquiry—ethical

individualism—is the correct method, and that common claims of collective

obligations or collective entitlements are therefore unfounded. Although I will

discuss some of the intuitive grounds for these views, I don’t intend to give a

comprehensive justification for them, and those who object to the views may just

as easily object to the grounds I offer for them. If you have a fundamentally

different conception of rights, or of ethical relations, this essay will

probably not convince you to become an anarchist. On the other hand, it may help

explain how principled commitment to a libertarian theory of rights—including a

robust defense of private property rights—is compatible with struggles

for equality, mutual aid, and social justice. It may also help show that

libertarian individualism does not depend on an atomized picture of human social

life, does not require indifference to oppression or exploitation other than

government coercion, and invites neither nostalgia for big business nor

conservatism towards social change. Thus, while my argument may not

directly convince those who are not already libertarians of some sort,

it may help to remove some of the obstacles that stop well-meaning Leftists from

accepting libertarian principles. In any case, it should show non-libertarians

that they need another line of argument: libertarianism has no necessary

connection with the "vulgar political economy" or "bourgeois liberalism" that

their criticism targets.

The threefold structure of my argument draws from the three demands made by

the original revolutionary Left in France: Liberty, Equality,

and Solidarity.[] I will argue that, rightly

understood, these demands are more intertwined than many contemporary

libertarians realize: each contributes an essential element to a radical

challenge to any form of coercive authority. Taken together, they undermine the

legitimacy of any form of government authority, including the

"limited government" imagined by minarchists. Minarchism eventually requires

abandoning your commitment to liberty; but the dilemma is obscured when

minarchists fracture the revolutionary triad, and seek "liberty" abstracted from

equality and solidarity, the intertwined values that give the demand for freedom

its life, its meaning, and its radicalism. Liberty, understood in light of

equality and solidarity, is a revolutionary doctrine demanding anarchy,

with no room for authoritarian mysticism and no excuse for arbitrary dominion,

no matter how "limited" or benign.

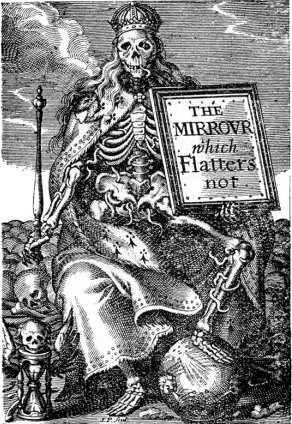

Liberty

Individual liberty is essential to political justice

for both minarchist and anarchist libertarians. Both understand political

liberty as freedom from organized coercion: force, under libertarian theory, can

only be legitimate in defense of an individual person’s

liberty, never when initiated against those who have not trespassed

against any identifiable victim. Libertarians often draw boundaries between

liberty and invasion through the principle of self-ownership: you are

rightly your own master, and nobody else, individually or collectively, is

entitled to claim you as their property.[] That

includes governments: self-ownership is held to be unconditional and

"prepolitical," in that it does not depend on the guarantees of political

constitutions or legislation, but rather logically precedes them and

constrains the constitutions and legislation that can legitimately be

established. Thus anarchists and minarchists agree that political power should

be subordinated to the principle of self-ownership, and everyone left alone to

do as she pleases with her own person and property provided she respects the

same freedom for others. But they disagree over what these principles entail.

Minarchists argue that the rights of liberty and self-defense, delegated and

institutionalized, establish the legitimacy of a "night-watchman"

State,[] limited by a written constitution

and devoted to the rule of law. For anarchists, the rights of liberty and

self-defense expose even the "night-watchman" State as professionalized

usurpation, and reveal all government laws and written constitutions as mere

paper without authority. Such a conflict demands explanation, and clarification

of the terms of the dispute.

I won’t hazard a definition of either "government" or "state" here,

but some essential features can be described. States have governments, and

governments, as such, claim authority over a defined range of territory

and citizens. Governments claim the right to issue legitimate orders to

anyone subject to them, and to use force to compel obedience.[] But

governments claim more than that: after all, I have the right to order

you out of my house, and to shove you out if you won’t go quietly. Governments

claim supreme authority over legally enforceable claims within

their territory; while I have a right to order you off my property, a government

claims the right to make and enforce decisive, final, and exclusive orders on

questions of legal right[]—for example, whether it

is my property, if there is a dispute, or whether you have a right to

stay there. That means the right to review, and possibly to overturn or punish,

my demands on you—to decisively settle the dispute, to enforce the

settlement over anyone’s objections, and deny to anyone outside the

government the right to supersede their final say on it. Some

governments—the totalitarian ones—assert supreme authority over every

aspect of life within their borders; but a "limited government" asserts

authority only over a defined range of issues, often enumerated in a

written constitution. Minarchists argue not only that governments should be

limited in their authority, but specifically that the supreme authority of

governments should be limited to the adjudication of disputes over individual

rights, and the organized enforcement of those rights. But even the most minimal

minarchy, at some point, must claim its citizens’ exclusive

allegiance—they must love, honor and obey, forsaking all others, or else

they deny the government the prerogative of sovereignty. And a

"government" without sovereign legal authority is no government at all.

Authority, in the political sense, is correlative with

deference. Insofar as Twain is subject to Norton’s authority, Twain is

obliged to defer to Norton’s decisions, and Norton can compel him to obey. But

the sort of deference must be carefully distinguished. notes that

An authoritative command must … be

distinguished from a persuasive argument. When I am commanded to do

something, I may choose to comply even though I am not being

threatened, because I am brought to believe that it is something

which I ought to do. If that is the case, then I am not, strictly

speaking, obeying a command, but rather acknowledging the force or

rightness of a prescription. … But the person himself [sic]

has no authority—or, to be more precise, my complying with his

command does not constitute an acknowledgment on my part of any such

authority. (, 6)

Reason is no respecter of persons, but authority is personal: if

Norton has legitimate authority over Twain, then Twain’s obligation to

defer doesn’t come from the nature of what Norton decided, but from the

fact that Norton decided it.[] Wolff’s point could be

sharpened by further distinguishing epistemic authority from

imperative authority. There are cases where you should defer to an

authority because she possesses some special expertise on the issue at

hand.[] But this is more scientific authority than

political authority, and not really what Wolff seems to have in mind. The reason

that lawyers bring their cases before the Supreme Court is not just that the

Nine have some special expertise on the requirements of the law. Maybe they do,

but the reason that others are supposed to defer to their judgment has

to do with the offices they personally hold; their status is

constitutive of the binding force of the judgment. However

expert a mere lawyer may be, her opinion still amounts only to a

brief, not a ruling, unless and until the judge personally

authorizes it. It’s not that the issue lies within the court’s

expertise, but that it (supposedly) lies within their

prerogative.

It is not enough, then, for a minarchist just to postulate an ideal

government that makes some rulings worth enforcing on their own merits.

If a judgment is worth enforcing on its own merits, then it surely is

perfectly legitimate to enforce it, but then the legitimacy comes from the

content of the judgment, not from its source.[]

That justifies enforcing the judge’s ruling, but it does not establish

that the judge’s authorization confers any special legitimacy on the

enforcement, above or beyond what private citizens could confer, either

individually or cooperatively in private "defense associations," given enough

wisdom, study, and application. Minarchists need a theory that legitimates

exclusive government authority through the special positions that

government agents occupy, and the sovereign status of the government

they represent. Without one, they have no justification for the special

prerogatives claimed by even the most scrupulously limited of governments.

I claim that minarchists cannot consistently offer the kind of

theory that they need to offer, because no possible theory can connect

sovereign authority to legitimacy, without breaking the

connection between legal right and individual liberty. My case

for this claim consists of three challenges, each developed in the anarchist

literature, which demonstrate a conflict between individual liberty and one of

the forms of special authority that minarchists have traditionally wanted

governments to exercise.[] Since the clearest expression of the first,

and most basic, challenge is in we might

call it the Childs challenge. Rand argues that a government must be strictly

limited to the defensive use of force in order to be morally distinguishable

from a robber gang.[] She holds that even the legitimate

functions of a properly limited government must be funded voluntarily

by the governed, condemning taxation in any form.[] However, she insists

on the legitimacy of sovereignty and explicitly rejects individualist

anarchism.[] Childs, accepting Rand’s description of a

government as "an institution that holds the exclusive power to

enforce certain rules of social conduct in a given geographical

area,"[] argues that no institution can claim that

authority and remain limited to the defensive use of force at the same time:

Suppose that I were distraught with the service of a

government in an Objectivist society. Suppose that I judged, being as rational

as I possibly could, that I could secure the protection of my contracts and the

retrieval of stolen goods at a cheaper price and with more efficiency. Suppose I

either decide to set up an institution to attain these ends, or patronize one

which a friend or a business colleague has established. Now, if he [sic] succeeds in setting up the agency, which provides all

the services of the Objectivist government, and restricts his more

efficient activities to the use of retaliation against aggressors, there are

only two alternatives as far as the "government" is concerned: (a) It can use

force or the threat of it against the new institution, in order to keep its

monopoly status in the given territory, thus initiating the use or threat of

physical force against one who has not himself initiated force. Obviously,

then, if it should choose this alternative, it would have initiated force.

Q.E.D. Or: (b) It can refrain from initiating force, and allow the new

institution to carry on its activities without interference. If it did this,

then the Objectivist "government" would become a truly marketplace institution,

and not a "government" at all. There would be competing agencies of protection,

defense and retaliation—in short, free market anarchism. (, ¶ 8)

Rand’s theory of limited government posits an institution with sovereign

authority over the use of force, but her theory of individual rights only allows

for the use of force in defense against invasions of rights. As long as

private defense agencies limit themselves to the defense of their clients’

rights, Rand cannot justify using force to suppress them. But if citizens are

free to cut their ties to the "government" and turn to private agencies for the

protection of their rights, then the so-called "government" no longer holds

sovereign authority to enforce its citizens’ rights; it becomes only one defense

agency among many.[] Childs formulated his argument as an

internal critique of Ayn Rand’s political theory, but his dilemma challenges

any theory combining libertarian rights with government sovereignty.

Any "limited government" must either be ready to forcibly suppress private

defense agencies—in which case it ceases to be limited, by initiating

violence against peaceful people—or else it must be ready to coexist with

them—abdicating its claim to sovereignty and ceasing to be a government.

Since maintaining sovereignty requires an act of aggression, any

government, in order to remain a government, must be ready to trample the

liberty of its citizens, in order to establish and enforce a coercive monopoly

over the protection of rights.[]

At this point, some minarchists—most famously —accept that a properly limited government cannot simply

suppress competition from rights-respecting defense agencies (without

ceasing to be properly limited), but reply that it can rightfully

constrain competing defense agencies to obey certain norms, and in

particular to respect certain procedural immunities for the accused. A lynch mob

has no right to demand that they be allowed to "compete" with courts; a properly

limited government has the right to prohibit procedures that impose unacceptable

risks of punishment on the innocent.[] If it can prohibit

unreliable procedures, then it can force defense associations either to adopt

permitted procedures or disband. But then government sovereignty reasserts

itself, as the government becomes "the only generally effective enforcer of a

prohibition on others’ using unreliable enforcement procedures … and …

oversees these procedures" (, 113–114). If a properly limited

government reserves the right to authorize enforcement by approved defense

agencies, and prohibit enforcement by rogue defense agencies, then it remains

the sovereign authorizer of enforcement, even if it becomes one of many

direct providers.

Governments probably are entitled to forbid enforcement procedures that

violate the procedural immunities due to the accused. But unless the minarchist

introduces some further reason to reserve this prerogative for the

government, the Childs challenge applies as much to the protection of procedural

immunities as to the ordinary protection of rights. If the government has a

right to suppress rogue agencies, then so does anyone, as a matter of

individual self-defense.[] The universality of the right

draws out a second point. Nozick makes the transition from dominant protective

agency to minimal State by using language that suggests deputizing

private citizens: the government makes a list of who can be trusted to enforce

the law, and if you’re not on the list, then the government will stop you from

taking the law into your own hands. What matters is whether or not the

government has given you permission to act as a law-enforcer. The

picture depends on a blurring of the distinction amongst argument, authoritative

testimony, and prerogative. Defense associations may have the right to stop

other enforcers from using unreliable procedures, but whether a procedure is

unacceptably risky or not is a matter of fact, which can be characterized and

discovered independently of the say-so of the government. The

government’s seal of approval plays no constitutive role in the right

of an agency to use procedures that are demonstrably legitimate, and the

government’s own procedures must be subject to objective criticism as

much as any private enforcer’s. A right to suppress unacceptably risky efforts

at enforcement establishes no right to demand direct oversight of agencies’

procedures,[] or to suppress "unauthorized" enforcers

simply for not having the official approval of the government.

The language of "permission," "prohibition," and "oversight" obscures the

distinction; but in fact the protection of procedural immunities is not properly

understood in terms of giving permission at all, but rather

respecting a general right.[] The more generally

and impersonally a defense agency specifies its procedural protections, the less

they will resemble anything that could intelligibly be described as "oversight,"

"giving permission," or , broadly, the exercise of political authority. The more

they resemble interventionist "oversight," "giving permission," or political

authority, the more they will tread on the freedom of innocent people to enforce

their own rights using reliable but unofficial procedures. The government in

Nozick’s "minimal State" must either adopt general policies allowing for free

competition without requiring grants of official permission—and once again

ceases to exercise sovereignty—or else it must enforce its demands of oversight

and official approval, even on agencies that are following reliable

procedures—and once again ceases to be limited to defensive uses of force.

There is another possible reply I find more promising—indeed, convincing.

Strictly speaking, Childs’s dilemma applies to only one branch of the

government: he demonstrates that governments cannot claim a monopoly on

enforcing the rights of citizens, i.e., on the executive

functions of government. It establishes that anyone, not just the government and

its official deputies, can enforce citizens’ rightful claims to person and

property. But how is it determined which claims are rightful, and

which claims are baseless? Robert Bidinotto has objected that anarchism

demands not only "’competition’ in the protection of rights," but also

"’competition’ in defining what ‘rights’ are" (, ¶ 20); without a government

established as the "final arbiter on the use of force in society" (, ¶ 25),

there is no way to fix objective rules for the assertion of rights, and no

possibility of meaningful settlement of disputes over rights-claims. So even if

a minimal government cannot claim a monopoly on the executive functions, perhaps

a "microscopic" government could claim a monopoly on

legislation.[]

Provided that the government legislature and government courts do not try to

interfere with protection of rights by private citizens or defense associations,

I cannot see how the Childs challenge could undermine sovereignty over

legislation. But a second challenge, vigorously expressed in the later works of

Lysander Spooner, can. In the Spooner argues that

all legislation is either criminal, tyrannical, or idle:[]

Let me then remind you that justice is an immutable, natural

principle; and not anything that can be made, unmade, or altered by

any human power. … Lawmakers, as they call themselves, can add

nothing to it, nor take anything from it. Therefore all their laws,

as they call them, – that is, all the laws of their own making, –

have no color of authority or obligation. It is a falsehood to call

them laws; for there is nothing in them that either creates men’s

[sic] duties or rights, or enlightens them as to their duties

or rights. … If they command men to do justice, they add nothing to

men’s obligation to do it, or to any man’s right to enforce it. They

are therefore mere idle wind, such as would be commands to consider

the day as day, and the night as night. If they command or license

any man to do injustice, they are criminal on their face. If they

command any man to do anything which justice does not require him to

do, they are simple, naked usurpations and tyrannies. If they forbid

any man to do anything, which justice could permit him to do, they

are criminal invasions of his natural and rightful liberty. In

whatever light, therefore, they are viewed, they are utterly

destitute of everything like authority or obligation. (, ¶Â¶

4–7)

Minarchists usually agree that governments have no legitimate authority to

command violations of individual rights, or to forbid acts permitted by

individual liberty—the motive for limiting government was the idea that

legitimate political authority only exists within the boundaries drawn by

individual rights. But Spooner’s point about laws that command justice or forbid

injustice—prohibiting murder, theft, rape, etc.—may be harder to grasp. It is,

after all, true that governments and defense associations are perfectly

justified in enforcing those laws. But what must be appreciated here is that the

obligation to follow those laws, and the right to enforce them, derives entirely

from the content of the laws and not their source. The

government is justified in enforcing those laws only because anybody

would be justified in enforcing justice, whether or not self-styled

legislators have signed off on a document stating "Murder is a crime most foul."

The document itself is idle; it neither obliges nor authorizes anyone to do

anything they were not already obliged or free to do. The government is not so

much making new laws that impose obligations, but (at best!)

making declarations that recognize preexisting

obligations—which could be objectively specified by anyone, with or without

official approval from anyone.[] Any right to override another’s assessment

would derive from objective and impersonal considerations of justice,

demonstrated through argument or attested on the basis of expertise,[]

not from political prerogatives invested in the so-called legislature.

Anyone, regardless of status, has the right to make correct declarations about

justice, and override or ignore incorrect declarations. With no special

prerogative to establish rights, and no special prerogative to enforce them (as

per the Childs challenge), the claim of "sovereignty" for a "properly limited

government" must involve either usurpation or idle pretense.

That said, I do think that there is one final straw for the

minarchist to grasp, even after the Childs challenge and the Spooner challenge

have been taken into account, relating to a lacuna in Spooner’s account of the

possible relationship between a piece of legislation and the background

principles of justice. Spooner discussed three possible cases: (1) the

legislation may demand something that contradicts what individual

rights require—making it criminal; (2) it may demand something that

exceeds what individual rights require—making it tyrannical; (3) it may

demand something identical to what individual rights require—making it

nugatory. Spooner’s argument presumes that the "prepolitical" framework of

individual rights determines every question of enforceable obligations,

leaving no room for legislators to exercise legitimate prerogative. But while

these options cover the bulk of both the criminal and the civil law, Spooner has

overlooked one important possibility: there may be cases where the principle of

self-ownership does not fully specify how to apply individual

rights in the case at hand.

It may be that respect for individual rights requires that cars going

opposite directions on a highway should drive on opposite sides—so that drivers

will not needlessly endanger each other’s lives. But self-ownership alone surely

has nothing to say about whether motorists should drive on the left or

the right. It requires that some rule be adopted, and that

once adopted, each motorist obey it. But which rule to adopt

is a question that needs to be settled by considerations other than individual

rights. Medieval legal writers described similar cases as reducing the

natural law (in the sense of making it more specific); the idea is to spell out

the details for cases where the principles of natural justice underdetermine the

correct application of individual rights. It may seem, then, that this ekes out

a place for positive law-making in spite of the Spooner challenge: since there

has to be some specification of how to apply rights in these cases, but

more than one specification is compatible with the requirements of individual

rights, a minarchist might think that you need a government to take on the

prerogative of specifying which one to adopt.[]

If the Childs challenge undermined the executive authority of the

government, and the Spooner challenge undermined its legislative

authority, you might think of this move as preserving judicial

authority for a sovereign government. Sovereignty here means the right to serve

as the final authority on setting out auxiliary principles for applying

individual rights to specific cases where the requirements of self-ownership are

vague or contingent. To be sure, the limits put on the scope of its authority by

the Childs challenge and the Spooner challenge would be severe. The government

would have no executive and no general legislature; it would have no special

privileges to enforce and the scope of its law-making would be limited to

ironing out minor details within a system of obligations almost entirely

predetermined by the non-aggression principle. It would be a sort of

"ultramicroscopic government," so small that its influence on the specification

and protection of rights could barely be detected at all.

Although I think that the problem of reducing the natural law is one of the

hardest problems for anarchist theory to resolve, I do not think that the

minarchist is actually in a stronger position than the anarchist. The difficulty

for the minarchist solution can be brought out with a final challenge, also from

the works of Lysander Spooner. This second Spooner challenge is expressed most

clearly in no. 1:

The question still remains, how comes such a thing as "a nation" to exist?

How do millions of men [sic], scattered over an

extensive territory – each gifted by nature with individual freedom; required by

the law of nature to call no man, or body of men, his masters; authorized by

that law to seek his own happiness in his own way, to do what he will with

himself and his property, so long as he does not trespass upon the equal liberty

of others; authorized also, by that law, to defend his own rights, and redress

his own wrongs; and to go to the assistance and defence of any of his fellow men

who may be suffering any kind of injustice – how do millions of such men

come to be a nation, in the first place? How is it that each of them

comes to be stripped of his natural, God-given rights, and to be incorporated,

compressed, compacted, and consolidated into a mass with other men, whom he

never saw; with whom he has no contract; and towards many of whom he has no

sentiments but fear, hatred, or contempt? How does he become subjected to the

control of men like himself, who, by nature, had no authority over him; but who

command him to do this, and forbid him to do that, as if they were his

sovereigns, and he their subject; and as if their wills and their interests were

the only standards of his duties and his rights; and who compel him to

submission under peril of confiscation, imprisonment, and death?

Clearly all this is the work of force, or fraud, or both.

…. We are, therefore, driven to the acknowledgment

that nations and governments, if they can rightfully exist at all, can exist

only by consent. (Section III, ¶Â¶ 1–6)

Spooner’s aim in is, famously, to demonstrate that

citizens are only obliged to recognize the sovereign authority when, and only

for as long as, they genuinely, individually consent to recognize its

authority. What I want to draw attention to are the reasons that

Spooner suggests for the requirement. Here, Spooner questions the notion of a

political jurisdiction, asking what by what right some gang

calling itself "the government," however strictly limited, gains

authority over otherwise unrelated people who never had anything to do with

them? If there is some question of different ways in which rights could be

applied, then what sort of process and what sorts of relationship justify the

special claim that even an ultramicroscopic government would make to establish

their judgment in preference to all the others?

Spooner suggests that genuine, individual consent can explain their authority

over a jurisdiction. Suppose that Twain and Kearney have a dispute over how long

land must be left unused before it can be reclaimed as abandoned property. If

they both agree to turn the question over to Norton and defer to his judgment,

then it’s clear how Norton got jurisdiction over the case: Twain and Kearney

agreed to bind themselves to his judgment. But suppose that Twain and

Kearney never agreed to turn the question over to Norton, perhaps never even had

anything to do with Norton at all. If Norton should insist that they should

still defer to his judgment, because he is the Emperor, then

Norton has the burden of explaining what binds Twain and Kearney to him in such

a way that his judgment is more authoritative than anybody’s arbitrary fiat.

Even if the vague boundary between between Kearney’s and Twain’s claims needs to

be made more precise, where does Norton, specifically, get the right to enforce

his specification, except by consent of the disputing parties?

If consent is the standard, then the consent must be genuine. In

particular, it must be possible to refuse consent, or to

withdraw it later once given.[] That means that

consent cannot justify any government body claiming permanent and

irrevocable sovereignty. If a court’s jurisdiction depends on the

consent of those who have put themselves under it, then each of those people

must be individually free to take herself out of the jurisdiction and create or

align herself with another jurisdiction. But without consent, it’s hard

to see what distinguishes the government’s assertion of special authority from

arbitrary fiat. If a community has settled on the rule of one year rather than

two for abandonment, the government has no authority to arbitrarily override the

settled conventions. If folks are divided over the right rule to follow, but

have agreed to submit the dispute to some third party whom they trust more than

the government, the government has no authority to butt in to enforce its own

decision over the agreed terms. If folks are divided over the right rule to

follow, and have not made any steps toward resolving the dispute, then the

government has no authority to arbitrarily force itself on them as the

arbiter.[]

Liberty cannot coexist with government sovereignty, however "limited." The

claim of sovereignty must be backed up by coercion at some point, given up or

reduced to a vacuous arrangement of words, whether sovereignty is claimed over

the enforcement of rights, the definition of rights, or the

application of rights. Any way you slice it, government sovereignty

means an invasion of individual freedom, and individual freedom means,

ultimately, freedom from the State.

Equality

The standard against which I have been measuring minarchist

governments in each of these three challenges is based on an intuitive notion of

Liberty that I have taken more or less for granted. That might expose me to

allegations that I’ve made my case by misapplying or inflating the concept of

"liberty" beyond the conceptual or material context that gives it meaning. In my

defense, I want to offer some remarks on the conceptual context within which I

think the principles of self-ownership and individual liberty arise, and to

consider two possible objections to the argument of the previous section. First,

it might be held that I have demonstrated a genuine conflict between individual

liberty and government authority, but that coercion is justified in the limited

case of establishing government sovereignty, either because some other important

value is at stake, or else because a little coercion is a necessary evil to

avoid much greater or much worse coercion. Or, it might be held that I have only

seemingly demonstrated a conflict between individual liberty and government

authority by applying the concepts of liberty and coercion outside of the

context within which they are meaningful: in this case, government authority

could not be properly characterized as either "coercive" or

"non-coercive," perhaps because (for example) notions such as coercion and

freedom are only meaningful within a system of rights, and a system of rights is

only meaningful in the context of a functioning legal system. I think that

either charge reflects a failure to appreciate the conceptual relationship

between the revolutionary demands for Liberty and

Equality.

Attaching my controversial understanding of

liberty to the standard of equality might seem less than

prudent, if my interlocutor is a minarchist libertarian. Modern

libertarians make demands for individual liberty with

passion and urgency; their reaction to demands for social

equality is more often tepid if not openly hostile. Criticism of

social inequality is much more likely to be heard from the mouths of

unreconstructed statists, and "egalitarianism" is hardly a term

of praise in most libertarian intellectual circles. But I shall argue

that equality, rightly understood, is the best grounds

for principled libertarianism. When the conception of individual

liberty is uprooted from the demand for social equality, the

radicalism of libertarianism withers; it also leaves the libertarian

open to a family of conceptual confusions which prop up many of the

common minarchist arguments against anarchism.

My task, then, is to explain what I mean by "equality, rightly understood." I

certainly do not intend to suggest that liberty is conceptually

dependent on economic equality (of either opportunity or

outcome), or on equality of socio-cultural status.[]

But the equality I have in mind is also much more substantive

than the formal "equality before the law" or "equality of rights" suggested by

some libertarians and classical liberals, and rightly criticized by Leftists as

an awfully thin glove over a very heavy fist. Formal equality within a statist

political system, pervaded with pillage and petty tyranny, is hardly worth

fighting for; the point is to challenge the system, not to be equally

shoved around by it. The conception of equality that I have in mind has a

history on the Left older and no less revolutionary than the redistributionist

conception of socioeconomic equality. It is the equality that the French

revolutionaries had in mind when they demanded egalité, and which the American revolutionaries had in mind

when they stated:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men [sic] are created equal, that they are endowed by their

Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and

the pursuit of Happiness. ( ¶ 2)

Jefferson is making revolutionary use of concepts drawn from the English

liberal tradition. Equality, for Jefferson, is the basis for

independence, and the grounds from which individual rights

derive.[] Locke elucidates the concept when he

characterizes a "state of Perfect freedom"—the state to which everyone is

naturally entitled—as

A State also of Equality, wherein all the Power and

Jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another: there

being nothing more evident, than that Creatures of the same species

and rank promiscuously born to all the same advantages of Nature, and

the use of the same faculties, should be equal one amongst another

without Subordination or Subjection …. (, II. 4. ¶ 2)

The Lockean conception of equality that underwrites Jefferson’s revolutionary

doctrine of individual liberty is, as has argued, equality

of political authority. Jefferson and Locke denied, as arbitrary, the

Old Regime’s claim of a natural entitlement to lordship over their fellow

creatures. Ranks of superior and inferior political authority were not

established by natural differences in station or ordained by the will of God

Almighty. Political coercion is the material expression of a claim of unequal

authority: one person is entitled to dictate terms over another’s person and

property, and the other can be forced to obey. Declaring universal equality thus

means denying all such claims of lordship, and, thus, asserting that everyone

has authority over herself, and over herself alone. Equality

is the context within which the principle of self-ownership, and thus the demand

for individual freedom, takes root. This connection can be seen most explicitly

in the second Spooner challenge above. Spooner’s demand to know how free and

independent people are "compacted" together into a State against their will is

intimately connected with the protest against arbitrary assertions of a

right to dominate the affairs of others. Long points out that neither

socioeconomic equality nor formal legal equality "calls into question

the authority of those who administer the legal system; such administrators are

merely required to ensure equality, of the relevant sort, among those

administered. … Lockean equality involves not merely equality

before legislators, judges, and police, but, far more crucially,

equality with legislators, judges, and police" (¶Â¶ 22–25).

Whether or not Jefferson was right to treat the equality of authority as

self-evident, a minarchist should hardly want to deny that it is

true. The idea that legitimate governments must be constrained by the

non-aggression principle no less than private citizens, and the

individualist conception of rights, seem clearly rooted in the notion

of equal authority.[]

But whenever a minarchist brandishes equality of authority against statism,

she also undermines her case for any form of State sovereignty.

Considering liberty in light of equality systematically undermines both of the

objections considered above, and justifies the unlimited demand for Liberty that

I have employed. Insofar as the first objection depends on consequentialist

calculation—holding that liberty can be sacrificed either in the name of other

goods, or in the name of maximizing the total amount of liberty going around—it

necessarily conflicts with a demand for equal authority. The objection

presupposes someone to do the consequentialist calculations, supposedly entitled

to treat all goods, no matter whom they belong to, as common booty to

be distributed. By claiming the right to volunteer not only her own

liberty, but also other people’s liberty for sacrificial duty, the

consequentialist exempts herself from the standard of equality,

pretending that she is entitled to stand over everyone and pass judgment on

their liberty, taking some from Peter and rendering some to Paul in the

name of the cause. Equality means that other people’s lives and livelihoods are

not hers to give, no matter the results she might get from it.[]

The second sort of objection conflicts with equality in a different way. It

suggests, not that someone can legitimately violate one person’s

liberty in order to secure benefits for others, but that the force involved in

establishing sovereignty cannot be assessed under standards of liberty at all,

because the categorization of force as either aggressive or

defensive is only meaningful within the context of a functioning

government legal order. Thus, that the demand for

liberty, when applied unconditionally outside the background context of a

limited sovereign government, divorces rights-claims from the "final standard"

to settle them, and degrades into a programme for unrestrained tyranny and civil

war.

But it is Bidinotto, not the anarchist, who strips the concept of liberty out

of its proper context. The objection depends on a particular picture of the

State and its laws, which is as metaphysically illusive as it is captivating.

The State is imagined as a sort of titan standing over civil society,

binding it to its will and acting on it from without. The constraints that a

particular government imposes under the mantle of State authority may be

tyrannical or just, but whether used properly or abused, the peculiar standpoint

and the constraining force of the State seem necessary for any stable social

order, and sufficient to decisively settle disputes just by being asserted.

Since anarchy dispenses with the external constraints of the State, the

minarchist feels that all rights-claims will be left, as it were, hanging in the

air, with no final authority to ground them. It is this mystique of the State

that Randolph Bourne set out to expose by distinguishing amongst the Nation, the

State, and the Government:

The State is the country acting as a political unit, it is the group

acting as a repository of force, determiner of law, arbiter of

justice. … Government on the other hand is synonymous with neither

State nor Nation. It is the machinery by which the nation, organized

as a State, carries out its State functions. Government is a

framework of the administration of laws, and the carrying out of the

public force. Government is the idea of the State put into practical

operation in the hands of definite, concrete, fallible men. It is the

visible sign of the invisible grace. It is the word made flesh. And

it has necessarily the limitations inherent in all practicality.

Government is the only form in which we can envisage the State, but

it is by no means identical with it. That the State is a mystical

conception is something that must never be forgotten. Its glamor and

its significance linger behind the framework of Government and direct

its activities. (, § 1 ¶Â¶ 8-9)

Equality of authority dulls the mystical glamor of

State authority. The law is a human institution, and the legitimate

authority of individual rights-claims does not need to be

grounded in the dominance of a sovereign, or proclaimed from a

standpoint beyond the fragile social relationships among

fallible, mortal human beings. A good thing, too, since there is no Olympian standpoint for the State to occupy; governments are

made of people with no more special authority than you or I—even

when they are speaking ex cathedra in the name of the State.

Rights are grounded in the claims that each of us, as ordinary human

beings, are entitled to hold each other to, and are implemented not

by paper laws but by the concrete social and cultural relationships

we participate in. shows that if the "final

standard" demanded by Bidinotto is the realistic finality

that comes from a broad consensus that an issue has been settled and

should not be revisited, then it can be achieved through anarchist

institutions no less than through a government; if the "finality"

demanded is some sort of self-applying, self-grounding finality

immune to even the possibility of further dispute, then that

is not available even under a government, the mystique of State

authority notwithstanding.[]

The choice is not between a system where disputes are never

meaningfully settled and one where they are, but between one in which

they are settled through a decentralized network of institutions

holding each other in check, or through a centralized hierarchy

forcing others to defer to it. And, as Long argues, anarchy actually

provides a better hope for disputes to be settled justly

than minarchy—especially when an arbitrator is herself a party to

the dispute—because under anarchy the watchers are themselves

watched, and are less able to force through unjust rulings simply in

virtue of their dominant position.

The context of a concept is often

conceived as a constraint on the concept, and context-dropping as a

matter of applying the concept more widely than it should be

applied. But dropping the context of a concept could make you go

wrong in either of two ways: improper abstraction might

inflate the application of the concept beyond its domain of

significance; or it might conceal the concept’s significance

in cases where it should be applied. Understood in the

context of Equality, the principle of Liberty becomes more

radical, not less, challenging all forms of State mysticism with the

standard of individual sovereignty. Dispelling the mystical

conception of the State also reveals the need for concrete attitudes,

practices and relationships to sustain a free society, not just paper

laws to "limit" tyranny. Which brings me to Solidarity.

Solidarity

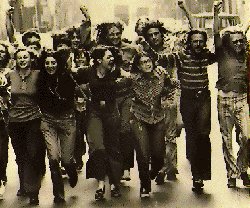

I have chosen the word "Solidarity" to stand for a family of

cultural and political commitments usually associated with the

radical Left, among them labor radicalism, populism,

internationalism, anti-racism, gay liberation, and radical feminism.

These commitments share a common concern with the class dynamics of

power and a sensitivity to expressions of non-governmental forms of

oppression. They demand fundamental change in the cultural and

material conditions faced by oppressed people, and propose that the

oppressed organize themselves into autonomous movements to struggle

for those changes. They also emphasize strikes, boycotts, mutual aid,

worker cooperatives, and other forms of collective action, both as a

means to social transformation and also as foundational institutions

of the transformed society once achieved. These shared concerns and

demands have often been summed up in the call for "social

justice"—a slogan assailed by and reflexively

associated, by libertarians and state Leftists alike, with expansion

of the anti-discrimination and welfare bureaucracies.

But solidaritarian ends can be separated from

authoritarian means, and the relationship between Liberty and

Solidarity has not always been so chilly. 19th century

libertarians, particularly the individualist anarchists associated

with Benjamin Tucker’s magazine Liberty, identified with the

cultural radicalism of their day – including the labor movement,

abolitionism, First Wave feminism, freethought, and "free love."

Indeed, while described his position as "Absolute Free

Trade; … laissez faire the universal rule" (, ¶ 21),

he and his circle routinely identified themselves as socialists—not

to set themselves against the ideal of the free market, but

against actually existing big business. They argued that

plutocratic control over finance and capital was the creature of, and

the driving force behind, government economic regimentation and

government-granted monopolies.[]

The Tuckerite individualists saw the invasive powers of the State as

intimately connected and mutually reinforcing with the exploitation

of labor, racism, patriarchy, and other forms of oppression, with

governments acting to enforce social privilege, and drawing

ideological and material support from existing power dynamics.[]

From their point of view, attacking statism alone, without addressing

the broader social context, would be narrow and ultimately

self-frustrating.

Today the leading intellectual force in the

effort to connect libertarianism with a comprehensive vision of human

liberation is Chris Sciabarra,[]

who has advanced the argument in a series of books and articles over

the past two decades, most extensively in his "Dialectics and

Liberty" trilogy (,

,

). Sciabarra persuasively

advocates a dialectical orientation in libertarian social

thought, which attends not only to the structural dynamics of statism

but also to the extragovernmental context of statism in

cultural, psychological, and philosophical dimensions. But unlike the

19th century individualists, Sciabarra argues that

dialectics pose a substantial challenge to libertarian

anarchism. In Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, he

sympathetically interprets Rand’s polemical defense of minarchism as

a dialectical effort to transcend a false dualism between statism and

anarchism (, 278-283). In Total Freedom he devotes four

chapters to a charitable but systematic critique of Rothbard’s

anarcho-capitalism, and the underlying conception of liberty as

"universally applicable, regardless of the context within which

it is embedded or applied" (, 218). Sciabarra argues that,

at crucial junctures, Rothbard idealizes the market and the State

into dualistic, opposed spheres, related only through "the

external, mutually antagonistic relationship between voluntarism and

coercion" (, 355). This dualism leads Rothbard to romanticize

market processes, proposing "the monistic, utopian resolution of

anarcho-capitalism, in which the state’s functions were fully

absorbed by the market" (360). Thus Rothbard limits libertarianism

to a narrow focus on structural and political questions, and exhibits

a "lack of attention to the vast context within which [libertarian

principles] might exist, evolve, and thrive" (355).[]

Whether or not Rothbard himself is actually

guilty of the "unanchored utopianism" Sciabarra attributes to him

(, 202), Sciabarra’s criticism identifies real strands of thought

within the individualist anarchist tradition.[]

But in light of the discussion of Equality above, it seems that

minarchists are actually far more prone to synoptic delusions and

narrowly political reform than anarchists: the mystique of State

authority depends on a picture of the State as an external constraint

on civil society, whereas egalitarian anarchism highlights

the fact that freedom is a matter of concrete relations within

society. In any case, the best response to Sciabarra’s challenge is

to exhibit a dialectical anarchism, which connects anarchism

with a systematic understanding and critique of the dynamics of

social power, both inside and outside of the State apparatus. To aid

in doing so, I’d like to set out some of the different possible

relationships between libertarianism and "thicker" bundles of

socio-cultural commitments, which would recommend integrating the

two:

Entailment thickness: the commitments might just be

applications of libertarian principle to some special case, following from

non-aggression simply in light of non-contradiction.[]

Application thickness: it might be that you could reject

commitments without formally contradicting the non-aggression

principle, but not without in fact interfering with its proper

application. Principles beyond libertarianism alone may be necessary

for determining where my rights end and yours begin, or stripping away

conceptual blinders that prevent certain violations of liberty from being

recognized as such.

Strategic thickness: certain ideas, practices, or

projects may be causal preconditions for a flourishing free society,

giving libertarians strategic reasons to endorse them. Although rejecting them

would be logically compatible with libertarianism, it might make it

harder for libertarian ideas to get much purchase, or might lead a free society

towards poverty, statism or civil war.

Grounds thickness: some commitments might be

consistent with the non-aggression principle, but might undermine or

contradict the deeper reasons that justify libertarian

principles. Although you could consistently accept libertarianism

without the bundle, you could not do so reasonably: rejecting the

bundle means rejecting the grounds for libertarianism.

Conjunction thickness: commitments might be worth

adopting for their own sakes, independent of libertarian

considerations. All that is asserted is that you ought to be a libertarian (for

whatever reason), and, as it happens, you also ought to accept some

further commitments (for independent reasons).

The two extreme cases, entailment thickness and conjunction thickness, can

largely be set aside, since the "relationship" between libertarianism and the

further commitment is either so tight (identity) or so loose (mere conjunction)

as to make the point vacuous. But the three intermediate cases of application

thickness, strategic thickness, and grounds thickness make deeper connections

between libertarianism and a rich set of further commitments that naturally

complement libertarianism.

Consider the conceptual and strategic reasons that libertarians have to

oppose authoritarianism, not only as enforced by governments but also

as expressed in culture, business, the family, and civil society. If

libertarianism is rooted in the principle of equality of authority,

then there are good reasons to think that not only political structures of

coercion, but also the whole system of status and unequal authority

deserves libertarian criticism. And it is important to realize that that system

includes not only exercises of coercive power, but also a knot of ideas,

practices, and institutions based on deference to traditionally constituted

authorities. In the political realm, these patterns of deference show up most

clearly in the honorary titles, submissive etiquette, and unquestioning

obedience extended to heads of state, judges, police, and other visible

representatives of government "law and order." Although these rituals and habits

of obedience exist against the backdrop of statist coercion and intimidation,

they are also often practiced voluntarily. Similar expectations of deference

show up, to greater or lesser degrees, in cultural attitudes towards bosses in

the workplace, and parents in the family. Submission to traditionally

constituted authorities is reinforced not only through violence and threats, but

also through art, humor, sermons, historiography, journalism, childrearing, etc.

Although political coercion is the most distinctive expression of inequality of

authority, you could—in principle—have an authoritarian

social order without the exercise of coercion. Even in an anarchist society,

everyone might voluntarily agree to bow and scrape when speaking before the

(mutually agreed-on) town Chief. So long as the expectation of deference was

backed up only by means of verbal harangues, social ostracism of "unruly"

dissenters, culturally glorifying the authorities, etc., it would violate

no-one’s individual liberty and could not justifiably be resisted with

force.

But while there’s nothing logically inconsistent about envisioning

these sorts of societies, it is certainly weird. If the underlying

reason for committing to libertarian politics is rooted in the equality of

political authority, then even strictly voluntary expressions of inequality are

hard to reasonably reconcile with libertarianism. Yes, the meek could

voluntarily agree to bow and scrape, and the proud could angrily but

nonviolently demand obsequious forms of address and immediate obedience to their

fiat. But why should they? Libertarian equality delegitimizes the

notion of a natural right to rule or dominate other people’s affairs; the vision

of human beings as rational, independent agents of their own destiny renders

deference and unquestioning obedience ridiculous at best, and probably dangerous

to liberty in the long run. While no-one should be forced to treat her

fellows with the respect due to equals, or cultivate independent self-reliance

and contempt for the arrogance of power, libertarians certainly can—and

should—criticize those who do not, and exhort our

fellows not to rely on authoritarian social institutions, for reasons of both

grounds and strategic thickness.

General commitments to anti-authoritarianism, if applied to specific forms of

social power, have far-reaching implications for the relationship between

libertarianism and anti-racism, gay liberation, and other movements for social

transformation. I have written elsewhere on the strategic and conceptual

importance of radical feminist insights to libertarianism, and vice

versa.[] The causal and conceptual interconnections

between patriarchal authority, the cult of violent masculinity, and the

militaristic State have been discussed by radical feminists such as Andrea

Dworkin and Robin Morgan, as well as radical libertarians such as Herbert

Spencer and, more recently, Carol Moore.[] Moreover, the

insights of feminists such as Susan Brownmiller into the pervasiveness of rape,

battery, and other forms of male violence against women, present both a crisis

and an opportunity for the application of libertarian principles.

Libertarianism professes to be a comprehensive theory of human freedom; what

supposedly distinguishes the libertarian theory of justice is that we concern

ourselves with violent coercion no matter who is practicing it. But

what feminists have forced into the public eye in the last 30 years is that we

live in a society where one out of every four women faces rape or battery by an

intimate partner,[] and where women are threatened or attacked

by men who profess to love them, because the men coercing them believe they have

a right to control "their" women. Male violence against women is nominally

illegal but nevertheless systematic, motivated by the desire for control,

culturally excused, and hideously ordinary. For libertarians, this should sound

eerily familiar; confronting the reality of male violence means nothing less

than recognizing the existence of a violent political order working alongside,

and independently of, the violent political order of statism.[]

Male supremacy has its own ideological rationalizations, its own propaganda, its

own expropriation, and its own violent enforcement; although often in league

with the male-dominated State, male violence is older, more invasive, closer to

home, and harder to escape than most forms of statism. To seriously oppose all

political violence, libertarians need to fight, at least, a two-front war,

against both statism and male supremacy. It is, then, important to note how the

ideological dichotomy between "personal" and "political" problems, so often

criticized by feminists,[] has tended to blank out systemic male

violence from libertarian analysis. And also how the writings of some

libertarians on the family—especially those identified with the

"paleolibertarian" political-cultural project—have amounted to little more

than outright denial of male violence. Hans-Hermann Hoppe, for example, goes so

far as to indulge in the conservative fantasy that the traditional "internal

layers and ranks of authority" in the family are actually bulwarks of

"resistance vis-a-vis the state" ( § IV). Those "ranks of authority"

in the family mean the pater familias; but whether

father-right is, at a given historical moment, in league with or at odds with

State prerogatives, the fact that it is so widely enforced by the threat or

practice of male violence makes enlisting it in the struggle against statism

look much like enlisting Stalin to fight Hitler—no matter who wins, we all

lose.

Considerations of grounds and strategy also

suggest important connections between anarchism and the virtue of

voluntary mutual aid between workers, in the form of

community organizations, charitable projects, and labor unions. Once

again, the underlying reasons for valuing Liberty also give

good reasons for committing to voluntary solidarity with

your fellow people. One could in principle believe that everyone

ought to be free to pursue her own ends while also holding

that nobody’s ends actually matter except her own.[]

But again, while the position is possible, it is weird; one

of the best reasons for being concerned about the freedom of others

to pursue their own ends is a certain generalized respect for the

importance of other people’s lives and the integrity of their

choices, which is intimately connected with the libertarian

conception of Equality. That says nothing in favor of forcing

you to participate in welfare schemes,[]

or robbing Peter to pay Paul; but it does say something for working

with your neighbors in voluntary cooperative efforts to

improve your own lives or the lives of others. It’s likely also that

networks of voluntary aid organizations would be strategically

important to individual flourishing in a free society, in which there

would be no expropriative welfare bureaucracy for people living with

poverty or precarity to fall back on. Projects reviving the

bottom-up, solidaritarian spirit of the independent unions and mutual

aid societies that flourished in the late 19th and early

20th centuries, before the rise of the welfare

bureaucracy, may be essential for a flourishing free society, and one

of the primary means by which workers could take control of their own

lives, without depending on either bosses or bureaucrats.[]

If 20th century libertarians have

mostly failed to emphasize the potential for cooperative mutual aid,

the failure can be traced to two related confusions, born of

undialectical analysis and the failure to integrate Liberty with

Solidarity. The first conflates the principles of mutual aid with

government coercion in the name of "social welfare"—most

dramatically in the visceral hostility most 20th century

libertarians expressed towards labor unionism. Libertarian critics

have often condemned unions as "bands of thugs,"[]

the government-privileged foot soldiers of a stagnant,

interventionist political economy. Currently existing labor unions do

use coercive means to organize—in the United States, employers are

forced to enter into collective bargaining with unions that gain

National Labor Relations Board recognition, and non-violent means of

opposing unionization drives, such as retaliatory firing, are legally

prohibited. The official, government-privileged union establishment

also has for decades sought more government planning and

economic intervention. But treating the existing union establishment

as representative of the essential features of organized labor

disregards the historical process by which unions were co-opted,

captured, and domesticated by the expanding State bureaucracy during

the 1920s-1950s. The process was achieved with the collaboration of

one conservative faction within the labor movement,

represented most visibly by the "business unionism" of the AFL,

which gained leverage over its many competitors and seats in the

back-rooms of power through the new system of patronage.[]

It would be hard to discover from the writings of anti-union

libertarians that labor unions existed before the Wagner Act of 1935,

or that around the turn of the century one of the most vibrant wings

of organized labor were the radical, anarchist-led unions, most

famously the I.W.W., which rejected all attempts to influence or

capture State power.[]

They argued that putting economic power into the government’s hands

deprived workers of control over their own fate, and wasted

unions’ resources on bureaucracy and partisan maneuvering. Although

they worked for incremental improvements in wages and conditions,

they ultimately hoped to win not reforms of the existing capitalist

system, but workers’ ownership of the "means of production"—the

land, factories, and tools they labored with—not through the

political means of expropriation (as the Marxists suggested), but

through the economic means of free association, agitation, direct

action, voluntary strikes, union solidarity, and mutual aid between

workers, which would "build a new society within the shell of the

old." The emerging new society, far from the central planning

boards of state socialism, would be a world of independent

contractors and worker-owned co-ops, organized from the bottom up by

the workers themselves.

It was only through the political collaboration

of the establishmentarian union bosses and the "Progressive"

business class—in the form of violent persecution of the radicals,

such as the Palmer raids, and government patronage to establishment

unions through the NLRB—that the centralized, statist unionism of

the AFL-CIO rose to dominance within the labor movement.[]

Union methods are legally regulated and union demands effectively

constrained to modest (and easily revoked) improvements in wages and

conditions—with issues such as workers’ voice in the workplace, let

alone control of the means of production, dropped entirely. The only

real power remaining to effect more substantial changes comes through

their power as organized blocs for lobbying and electioneering. If

unionism is today mostly statist, then it is because unions are

largely what the State has made them, through the usual carrots and

sticks of government interventionism.

General Motors has benefited at least as

much from government patronage as the UAW, yet libertarian criticism

of the magnates of state capitalism is hardly extended to business as

such in the way that criticism of existing unions is routinely

extended to any form of organized labor. The difference in treatment

is no doubt closely connected with the emphasis many 20th

century libertarians placed on defending capitalism against the

attacks of state socialists. While they were right to see that

existing modes of production should not be further distorted

by even greater government regimentation, this insight was often

perverted into the delusion that existing modes of production would

be the natural outcome of an undistorted market. The

confusion has been encouraged by systematic ambiguity in the term

"capitalism," which has been used to name at least three

different economic systems:

The free market: any economic order that emerges from

voluntary exchanges of property and labor, free of government intervention and

other forms of systemic coercion.

The corporate State: government intervention favoring

cartelized big business, through subsidies, tax-funded infrastructure, central

banking, production boards, eminent domain seizures, government union-busting,

etc.

Alienation of labor: a specific form of labor market, in

which the dominant economic activity is production in workplaces strictly

divided by class, where most workers work for a boss, in return for a

wage, surviving by renting out their labor to someone else. The shop, and the

tools and facilities that make it run, are owned by the boss or by absentee

owners to whom the boss reports, not by the workers themselves.

Since government intervention always ends with the barrel of a gun, free

market "capitalism" and corporate state "capitalism" cannot coexist at the same

time and in the same respect. "Capitalism" in the third sense—the

alienation of labor—is a category independent of "capitalism" in

either of the first two senses. There are many ways that a labor market might

turn out; it could be organized into traditional employer-employee

relationships, worker co-ops, community workers’ councils, or a diffuse network

of shopkeeps and independent contractors. Unflinching free marketeers might

advocate any of these, or might be indifferent as to which prevails;

interventionist statists might also favor traditional employer-employee

relationships (as under fascism) or any number of different arrangements (as

under state communism). Once these three senses are disentangled, it is

important to see how 20th century libertarian defenses of

"capitalism" against interventionist critique have fallen into a second

conflation, between economic defenses of (1) the free market, and (2, 3) the way

that big business operates in the unfree market that actually exists today. This

confused approach, aptly dubbed "vulgar libertarianism" by Kevin Carson,[]

obscures the ways in which actually existing businesses benefit from pervasive

government intervention, and blinds "capitalist" libertarians to the affinity

between anti-statist models of labor organizing and libertarian defenses of free

markets.

Disentangling free market economics from the particular market structure of

alienated labor reveals some good reasons to think that there are serious

economic problems with bureaucratic, centralized corporate commerce

that rose to dominance in the 19th and 20th centuries under the

auspices of "Nationalist" and "Progressive" interventionism.[]

Central planners face the knowledge problems identified by Mises, Hayek, and

Rothbard whether those planners are government or corporate bureaucrats.[] If

workers are often deeply unhappy with the regimented, authoritarian structure of

corporate workplaces, then there is also reason to believe that many would

happily dump the bosses off their backs in favor of more autonomous forms of

work, as those become widespread, successful, and economically reliable. Thus

there is reason to think that in a free market less hierarchical, less

centralized, more worker-focused forms of production would multiply and

bureaucratic big business would wither under the pressure of

competition.[] Since the cooperative, bottom-up model of

labor unionism offers one of the best existing models for practically asserting

workers’ self-interest, and ultimately replacing boss-centric industry with

decentralized, worker-centric production, there are good reasons for

libertarians to integrate wildcat unionism into their understanding of social

power.

Solidaritarian considerations may also shed some light on the standing debate

amongst libertarians over secession and constitutional centralism. Liberty in

the abstract demands a universal right of secession; to keep any one

person or any group of people under a government that they wish to exit requires

you to violate their individual liberty in at least one of the three ways

challenged above. But voluntarily organized protection agencies, arbiters, etc.

could still claim wide or narrow jurisdictions, and could organize their

administrative and juridical functions into rigid hierarchies or take a more

"horizontal," decentralized approach. Affirming a right of secession

does not answer the constitutional question of which free arrangement

libertarians ought to prefer. But the same solidaritarian considerations that

tell against centralization and hierarchy in making widgets should tell even

more strongly against centralization and hierarchy in political power. The

pretensions of the powerful threaten a free society when it is hard to defend

yourself physically against abuses of the power entrusted to defense

associations, or intellectually against the allure of State mysticism. And there

are good prima facie reasons to suppose that people will be better able

to resist both threats by devolving power from centralized seats of power down

to the local level, with arbitration and enforcement handled face-to-face

through diffuse networks of local associations, rather than mediated through

powerful, bureaucratized hegemons.

Centralists may object that the historical record is more complex, and less

favorable to decentralism, than prima facie considerations would suggest.

While a centralized political power has more resources and a wider scope to

enforce coercive demands, local powers are often more subject to parochial

prejudices, and can often enforce them with force that is less diffuse, closer

to home, and therefore more intense than anything a mighty but remote central

government could muster. American history seems to illustrate this point

dramatically with the case of the Confederacy, in which the opponents of federal

power urged secession in order to strengthen and perpetuate the absolute tyranny

of chattel slavery.[] But what is needed here is a more

radical decentralism, dissociated from the humbug of "states’ rights."

Decentralist libertarians are perfectly justified in supporting the

white Southerners’ right to secede, and condemning the bayonet-point Unionism of

the Civil War—provided that they also support black slaves’

rights to secede from the Southern states, and condemn the bayonet-point

paternalism of the Southern slave-lords.

The approach here is to condemn the

federal war against secession, while also supporting the efforts of black

Southerners to free themselves, through escape or open rebellion.[]

The problem with the Confederacy was not the defiance of federal

authority, but the elevation of state authority over the objections of

poor whites and black slaves: too much, not too little, centralized power.