Sunday Ego Blogging / Shameless Self-promotion Sunday #16

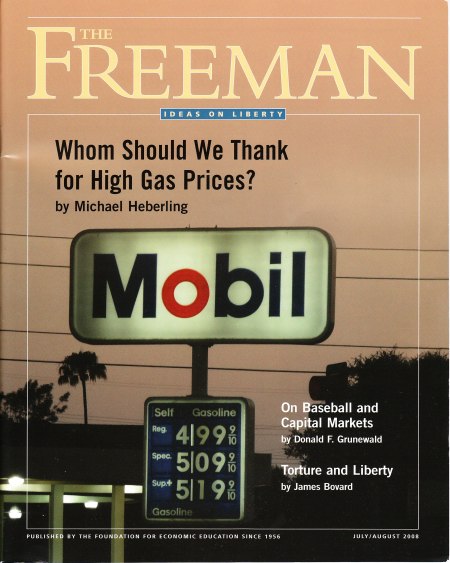

It’s Sunday again; that means it’s time for Shameless Self-Promotion. This Sunday, unlike most, I’ll be leading off, because here’s what I received in the mail a few days ago:

Libertarianism Through Thick and Thin

To what extent should libertarians concern themselves with social commitments, practices, projects, or movements that seek social outcomes beyond, or other than, the standard libertarian commitment to expanding the scope of freedom from government coercion?

Clearly, a consistent and principled libertarian cannot support efforts or beliefs that are contrary to libertarian principles—such as efforts to engineer social outcomes by means of government intervention. But if coercive laws have been taken off the table, then what should libertarians say about other religious, philosophical, social, or cultural commitments that pursue their ends through noncoercive means, such as targeted moral agitation, mass education, artistic or literary propaganda, charity, mutual aid, public praise, ridicule, social ostracism, targeted boycotts, social investing, slowdowns and strikes in a particular shop, general strikes, or other forms of solidarity and coordinated action? Which social movements should they oppose,which should they support, and toward which should they counsel indifference? And how do we tell the difference?

In other words, should libertarianism be seen as a

thincommitment, which can be happily joined to absolutely any set of values and projects,so long as it is peaceful,or is it better to treat it as one strand among others in athickbundle of intertwined social commitments? Such disputes are often intimately connected with other disputes concerning the specifics of libertarian rights theory or class analysis and the mechanisms of social power. To grasp what’s at stake, it will be necessary to make the question more precise and to tease out the distinctions among some of the different possible relationships between libertarianism andthickerbundles of social, cultural, religious, or philosophical commitments, which might recommend integrating the two on some level or another.. . .

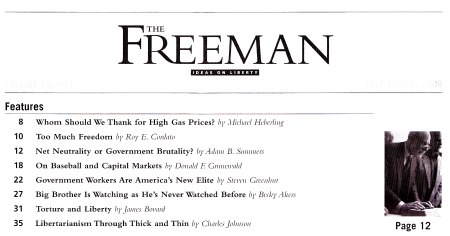

— Libertarianism Through Thick and Thin, in The Freeman: Ideas on Liberty 58.6 (July/August 2008), pp. 35–39.

You can read the whole thing (warning: PDF blob) at The Freeman‘s online edition. Enjoy! FEE’s website doesn’t (yet) support online comments, but I’d be glad to hear what you think in the comments section over here.

One note about the article: it had to be shortened substantially both for reasons of space and considerations of the likely audience. I’ve talked with Sheldon, and I’ll be posting the longer version of the essay here at Rad Geek People’s Daily in a couple of weeks.[1]

So, that’s me; what about you? What did you all write about this week? Leave a link and a short description for your post in the comments.

- [1][Edit. The expanded version is now available as GT 2008-10-03: Libertarianism Through Thick and Thin. –R.G.]↩