For your own safety, natch.

450 illegal tamales from Mexico seized at LAX and ‘incinerated’ (not steamed)

Apparently there are illegal tamales.

A passenger at Los Angeles International Airport learned that the hard way earlier this month when he tried to bring pork tamales into the U.S. from Mexico.

The passenger arrived from Mexico on Nov. 2 and was stopped by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agriculture specialists, who found 450 pork tamales wrapped in plastic bags in the passenger's luggage.

The passenger apparently denied that the tamales were made with pork, which is on the list of products that travelers may not bring into the country under customs regulations.

For many families, tamales are a quintessential holiday tradition. Making a batch takes days of planning and exhaustive preparation — all for a tasty bite of corn masa, red chile mole and pork, beef or chicken.

The passenger would have been in the clear had he tried to bring sweet tamales – or those all masa ones that always seem to be left over.

. . . The passenger, who was not identified, was fined $1,000 because authorities believed the tamales were going to be sold and distributed.

As for the tamales, they met their demise. But not in the traditional manner: By being devoured.

All 450 of them were destroyed. The tamales were literally "incinerated," a Customs and Border Protection spokesman said.

–Veronica Rocha, 450 illegal tamales from Mexico seized at LAX

Los Angeles Times, 18 November 2015.

Now of course Customs is being ludicrous, mean-spirited, invasive and petty. This is a heavy fine, and a pointless assault on the freedom of a peaceful traveler who did nothing to violate the rights of even a single living soul. It’s also a waste of perfectly good tamales, and just kind of a damned shame all around. But it is — qué pena! — just the most recent installment in a long, ludicrous history of American government’s mean-spirited and petty war on tamales and tamaleros:

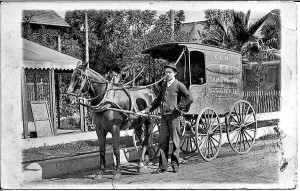

By 1901, more than a hundred tamale wagons roamed Los Angeles, each paying a dollar a month for a city business license. Their popularity spurred others in outlying cities to follow their example. In 1906, Sonoran immigrant Alejandro Morales began selling his wife’s tamales from a wagon he commandeered through Anaheim. Morales, a ditch digger by trade, grew the concept into a restaurant, then a tamale factory, then Alex Foods, a multimillion-dollar empire now known as Don Miguel Mexican Foods.

. . . It wasn’t just Latinos who operated tamale wagons — African Americans, European immigrants and whites also partook in the industry. In 1905, even the YMCA opened a temporary tamale wagon to raise funds so it could send a boy’s track and field team to compete in Portland, Ore.

Strangers coming to Los Angeles,

reported The Times, remark at the presence of so many outdoor restaurants, and marvel at the system which permits men ... to set up places of business in the public streets ... competing with businessmen who pay high rents for rooms in which to serve the public with food.

Not everyone appreciated those first loncheras. L.A.’s press sensationalized any fight, quarrel or theft committed around the eateries, leading to a perception in polite circles that they weren’t safe (typical headline: “Says the Tamale Wagon is a Nursery of Crime”). As early as 1892, officials tried to ban them; in 1897, the City Council proposed to not allow tamale wagons to open until nine at night at the behest of restaurant owners who didn’t like their crowds. Four years later, Police Chief Charles Elton recommended they close at 1 a.m. because they offered “a refuge for drunks who seek the streets when the saloons are closed for the night.”

Los Angeles school trustees constructed kitchens at the city’s high schools (including the first prep cafeteria in the country at Los Angeles High) in 1905 to offer healthier lunches after having “long waged a crusade against the tamale wagons,” according to the Herald. And in 1910, 100 downtown businessmen signed a letter asking the council that tamale wagons be prohibited because they didn’t reflect well on the district.

The tamaleros fought back with their most powerful weapon: their fans. In 1903, when the council tried to outlaw them altogether, they formed a mutual-aid society and presented the council a petition with the signatures of more than 500 customers that read, in part: “We claim that the lunch wagons are catering to an appreciative public, and to deprive the people of these convenient eating places would prove a great loss to the many local merchants who sell the wagon proprietors various supplies.”

They also found an ally in Councilman Fred Wheeler. In 1920, he offered an impassioned defense in council chambers when tamale wagons once again faced the ax. “The tamale put Los Angeles on the map,” he thundered. “These wagons are almost an institution of our city. Cabrillo and his sailors are said to have found them here when they landed. Drive these wagons from our streets? Never!”

Wheeler convinced his fellow councilmen to spare the tamale wagons that year but wasn’t as lucky in 1924, when a resolution booted tamaleros from the plaza. They continued as usual, though, a move that sparked The Times to quip, “Those lunch carts have more lives than the eighty-one incarnations of Methuselah’s nine cats.”

By then, the wagons sold more than tamales — the massive wave of migrants from central Mexico over the previous 20 years had introduced other Mexican delicacies to the city, such as barbacoa, menudo and tacos. But their era was waning. “They belong not to the new order of things,” The Times editorialized in 1924. “They were born of the pueblo — they perish in the metropolis.”

The plaza, of course, transformed into Olvera Street, as a new generation of Angelenos wanted a more refined Mexican culinary experience than that offered by the chaos of Tamale Row. As the automobile grew in popularity, Latino families loaded up their trucks and drove through East Los Angeles selling food before settling in downtown, the precursor to today’s loncheras.

By 1929, when Samuel C. Wilhite received a patent for a “Tamale Inn” — a tamale wagon shaped like its eponymous snack complete with awning, rows of windows, and even steps — there was no need for it. He parked it on Whittier Boulevard and named it the Tamale, where the structure still stands, although it’s currently a beauty salon. The last tamale wagon on Southern California’s roads belonged to the Morales family: their Tamale Wagon, a legendary sprint car that captured the minds of race fans for decades.

–Gustavo Arellano, Tamales, Los Angeles’ First Street Food

Los Angeles Times, 8 September 2011.

Free the tamales and all political prisoners.

See also.