This book tells the story of how one kind of slavery made another kind of liberty possible in eighteenth-century New York, a place whose past has long been buried. It was a beautiful city, a crisscross of crooked cobblestone streets boasting both grand and petty charms: a grassy park at the Bowling Green, the stone arches at City Hall, beech trees shading Broadway like so many parasols, and, off rocky beaches, the best oysters anywhere. I found it extremely pleasant to walk the town,

one visitor wrote in 1748, for it seemed like a garden.

But on this granite island poking out like a sharp tooth between the Hudson and East rivers, one in five inhabitants was enslaved, making Manhattan second only to Charleston, South Carolina, in a wretched calculus of urban unfreedom.

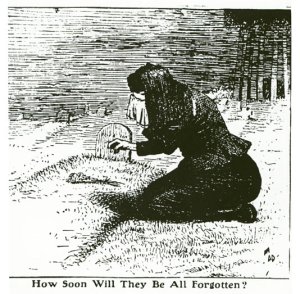

New York was a slave city. Its most infamous episode is hardly known today: over a few short weeks in 1741, ten fires blazed across the city. Nearly two hundred slaves were suspected of conspiring to burn every building and murder every white. Tried and convicted before the colony’s Supreme court, thirteen black men were burned at the stake. Seventeen more were hanged, two of their dead bodies chained to posts not far from the Negroes Burial Ground, left to bloat and rot. One jailed man cut his own throat. Another eighty-four men and women were sold into yet more miserable, bone-crushing slavery in the Caribbean. Two white men and two white women, the alleged ringleaders, were hanged, one of them in chains; seven more white men were pardoned on the condition that they never set foot in New York again.

What happened in New York in 1741 is so horrifying–Bonfires of the Negroes,

one colonist called it–that it’s easy to be blinded by the brightness of the flames. But step back, let the fires flicker in the distance, and they cast their light not only on the 1741 slave conspiracy but on the American paradox, illuminating a far better known episode in New York’s past: the 1735 trial of the printer John Peter Zenger.

In 1732, a forty-two-year-old English gentleman named William Cosby arrived in New York, having been appointed governor by the king. New Yorkers soon learned, to their dismay, that their new governor ruled y a three-word philosophy: God damn ye. Rage at Cosby’s ill-considered appointment grew with his every abuse of the governorship. Determined to oust Cosby from power, James Alexander, a prominent lawyer, hired Zenger, a German immigrant, to publish an opposition newspaper. Alexander supplied scathing, unsigned editorials criticizing the governor’s administration; Zenger set the type. The first issue of Zenger’s New-York Weekly Journal was printed in November 1733. Cosby could not, would not abide it. He assigned Daniel Horsmanden, an ambitious forty-year-old Englishman new to the city, to a committee, charged with pointing out the particular Seditious paragraphs

in Zenger’s newspaper. The governor then ordered the incendiary issues of Zenger’s newspaper burned, and had Zenger arrested for libel.

Zenger was tried before the province’s Supreme Court in 1735. His attorney did not deny that Cosby was the object of the editorials in the New-York Weekly Journal. Instead, he argued, first, that Zenger was innocent because what he printed was true, and second, that freedom of the press was especially necessary in the colonies, where other checks against governors’ powers were weakened by their distance from England. It was an almost impossibly brilliant defense, which at once defied legal precedent–before the Zenger case, truth had never been a defense against libel–and had the effect of putting the governor on trial, just what Zenger’s attorney wanted, since William Cosby, God damn him, was a man no jury could love. Zenger was acquitted. The next year, James Alexander prepared and Zenger printed A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, which was soon after reprinted in Boston and London. It made Zenger famous.

But the trial of John Peter Zenger is merely the best-known episode in the political maelstrom that was early eighteenth-century New York. We are in the midst of Party flames,

Daniel Horsmanden wrly observed in 1734, as Cosby’s high-handedness ignited the city. Horsmanden wrote in an age when political parties were considered sinister, invidious, and destructive of good government. As Alexander Pope put it in 1727, Party is the madness of many, for the gain of a few.

Or, as Viscount St. John Bolingbroke remarked in his 1733 Dissertation upon Parties: The spirit of party … inspires animosity and breeds rancour.

Nor did the distaste for parties diminish over the course of the century. In 1789, Thomas Jefferson wrote: If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.

Parties they may have despised, but, with William Cosby in the governor’s office, New Yorkers formed them, dividing themselves between the opposition Country Party and the Court Party, loyal to the governor. Even Cosby’s death in March 1736 failed to extinguish New York’s Party flames.

Alexander and his allies challenged the authority of Cosby’s successor, George Clarke, and established a rival government. Warned of a plot to seize his person or kill him in the Attempt,

Clarke retreated to Fort George, at the southern tip of Manhattan, & put the place in a posture of Defence.

In the eyes of one New Yorker, we had all the appearance of a civil War.

And then: nothing. No shots were fired. Nor was any peace ever brokered: the crisis did no so much resolve as it dissipated. Soon after barricading himself in Fort George, Clarke received orders from London confirming his appointment. The rival government was disbanded. By the end of 1736, Daniel Horsmanden could boast, Zenger is perfectly silent as to polliticks.

Meanwhile, Clarke rewarded party loyalists: in 1737 he appointed Horsmanden to a vacant seat on the Supreme Court. But Clarke proved a more moderate man than his predecessor. By 1739, under his stewardship, the colony quieted.

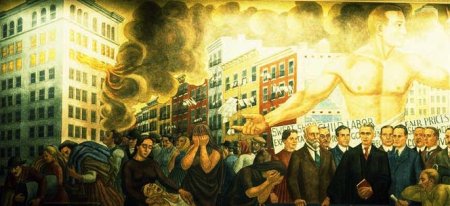

What happened in New York City in the 1730s was much more than a dispute over the freedom of the press. It was a dispute about the nature of political opposition, during which New Yorkers briefly entertained the heretical idea that parties were not only necessary in free Government, but of great Service to the Public.

As even a supporter of Cosby wrote in 1734, Parties are a check upon one another, and by keeping the Ambition of one another within Bounds, serve to maintain the public Liberty.

And it was, equally, a debate about the power of governors, the nature of empire, and the role of the law in defending Americans against arbitrary authority–the kind of authority that constituted tyranny, the kind of authority that made men slaves. James Alexander saw himself as a defender of the rule of law in a world that, because of its very great distance from England, had come to be ruled by men. His opposition was not so much a failure as a particularly spectacular stretch of road along a bumpy, crooked path full of detours that, over the course of the century, led to American independence. Because of it, New York became infamous for its unruly spirit of independency.

Clarke, shocked, reported to his superiors in England that New Yorkers believe if a Governor misbehave himself they may depose him and set up an other.

the leaders of the Country Party trod very near

to what, in the 1730s, went by the name of treason. A generation later, their sons would call it revolution.

In early 1741, less than two years after Clarke calmed the province, ten fires swept through the city. Fort George was nearly destroyed; Clarke’s own mansion, inside the fort, burned to the ground. Daniel Horsmanden was convinced that the fires had been set on Foot by some villainous Confederacy of latent Enemies amongst us,

a confederacy that sounded a good deal like a violent political party. But which enemies? No longer fearful that Country Party agitators were attempting to take his life, Clarke, at Horsmanden’s urging, turned his suspicion on the city’s slaves. With each new fire, panicked white New Yorkers cried from street corners, The Negroes are rising!

Early evidence collected by a grand jury appointed by the Supreme Court hinted at a vast and elaborate conspiracy: on the outskirts of the city, in a tavern owned by a poor and obscure English cobbler named John Hughson, tens and possibly hundreds of black men had been meeting secretly, gathering weapons and plotting to burn the city, murder every white man, appoint Hughson their king, and elect a slave named Caesar governor.

This political opposition was far more dangerous than anything led by James Alexander. The slave plot to depose one governor and set up another–a black governor–involved not newspapers and petitions but arson and murder. It had to be stopped. In the spring and summer of 1741, New York magistrates arrested 20 whies and 152 blacks. To Horsmanden, it seemed very probable that most of the Negroes in Town were corrupted.

Eighty black men and one black woman confessed and named names, sending still more to the gallows and the stake.

That summer, a New Englander wrote an anonymous letter to New York. I am a stranger to you & to New York,

he began. But he had heard of the bloody Tragedy

afflicting the city: the relentless cycle of arrests, accusations, hasty trials, executions, and more arrests. This puts me in mind of our New England Witchcraft in the year 1692,

he remarked, Which if I dont mistake New York justly reproached us for, & mockt at our Credulity about.

Here was no idle observation. The 1741 New York conspiracy trials and the 1692 Salem witchcraft trials had much in common. Except that what happened in New York in 1741 was worse, and has been almost entirely forgotten. In Salem, twenty people were executed, compared to New York’s thirty-four, and none were burned at the stake. However much it looks like Salem in 1692, what happened in New York in 1741 had more to do with revolution than witchcraft. and it is inseparable from the wrenching crisis of the 1730s, not least because the fires in 1741 included attacks on property owned by key members of the Court Party; lawyers from both sides of the aisle in the legal battles of the 1730s joined together to prosecute slaves in 1741; and slaves owned by prominent members of the Country Party proved especially vulnerable to prosecution.

But the threads that tie together the crises of the 1730s and 1741 are longer than the list of participants. The 1741 conspiracy and the 1730s opposition party were two faces of the same coin. By the standards of the day, both faces were ugly, disfigured, deformed; they threatened the order of things. But one was very much more dangerous than the other: Alexander’s political party plotted to depose the governor; the city’s slaves, allegedly, plotted to kill him. The difference made Alexander’s opposition seem, relative to slave rebellion, harmless, and in doing so made the world safer for democracy, or at least, and less grandly, both more amenable to and more anxious about the gradual and halting rise of political parties.

Whether enslaved men and women actually conspired in New York in 1741 is a question whose answer lies buried deep in the evidence, if it survives at all. It is worth excavating carefully. But even the specter of a slave conspiracy cast a dark shadow across the political landscape. Slavery was, always and everywhere, a political issue, but what happened in New York suggests that it exerted a more powerful influence on political life: slaves suspected of conspiracy constituted both a phantom political party and an ever-threatening revolution. In the 1730s and ’40s, the American Revolution was years away and the real emergence of political parties in the new United States, a fitful process at best, would have to wait until the last decade of the eighteenth century. (Indeed, one reason that colonists only embraced revolution with ambivalence and accepted parties by fits and starts may be that slavery alternately ignited and extinguished party flames: the threat of black rebellion made white political opposition palatable, even as it established its limits and helped heal the divisions it created.) But during those fateful months in the spring and summer of 1741, New York’s Court Party, still reeling from the Country Party’s experiments in political opposition, attempted to douse party flames by burning black men at the stake. New York is not America, but what happened in that eighteenth-century slave city tells one story, and a profoundly troubling one, of how slavery destabilized–and created–American politics.

–Jill Lepore (2005), New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan (ISBN 1400040299). xii–xviii.

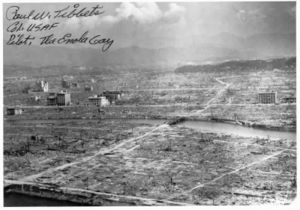

Sixty-one years ago today, at 8:15am in the morning, Thomas Ferebee, acting under the direct command of Paul Tibbets, on the orders of the United States government, dropped an atomic bomb over the city center of Hiroshima, Japan. When the bomb was dropped the city had a population of about 255,000 people. About 70,000–80,000 people were instantly killed by the shockwave, fireball, and radiation. By the end of 1945, tens of thousands more had died from their wounds, from radiation sickness, and from cancer related to the radioactivity. It’s estimated that about 140,000 people — more than half the population of the city — died in the nuclear massacre. The overwhelming majority of people killed were civilians: Hiroshima had only a couple of relatively unimportant military bases, and they were located on the edges of town, miles away from ground zero in the central city.

Sixty-one years ago today, at 8:15am in the morning, Thomas Ferebee, acting under the direct command of Paul Tibbets, on the orders of the United States government, dropped an atomic bomb over the city center of Hiroshima, Japan. When the bomb was dropped the city had a population of about 255,000 people. About 70,000–80,000 people were instantly killed by the shockwave, fireball, and radiation. By the end of 1945, tens of thousands more had died from their wounds, from radiation sickness, and from cancer related to the radioactivity. It’s estimated that about 140,000 people — more than half the population of the city — died in the nuclear massacre. The overwhelming majority of people killed were civilians: Hiroshima had only a couple of relatively unimportant military bases, and they were located on the edges of town, miles away from ground zero in the central city.