(Via private correspondence from an ALLy in Occupied Cascadia.)

Here’s something I wrote about last year in my article for The Freeman:

Had the city government not made use of its supposed title to the abandoned land [to fence off the lot that the Umoja Village shanty-town had been built on], it no doubt could have made use of state and federal building codes to ensure that residents would be forced back into homelessness—for their own safety, of course. That is in fact what a county health commission in Indiana did to a 93-year-old man named Thelmon Green, who lived in his '86 Chevrolet van, which the local towing company allowed him to keep on its lot. Many people thrown into poverty by a sudden financial catastrophe live out of a car for weeks or months until they get back on their feet. Living in a car is cramped, but it beats living on the streets: a car means a place you can have to yourself, which holds your possessions, with doors you can lock, and sometimes even air conditioning and heating. But staying in a car over the long term is much harder to manage without running afoul of the law. Thelmon Green got by well enough in his van for ten years, but when the Indianapolis Star printed a human-interest story on him last December, the county health commission took notice and promptly ordered Green evicted from his own van, in the name of the local housing code.

Or, hell, they might not even bother with the regulatory formalities. Sometimes the cops just roll up on you for a welfare check

and then take the opportunity to steal your home.

For example, Contia Orsby is a 58 year old black woman, who has spent most of her life helping sick people and, as far as I know, never did any real harm to anybody. She’s originally from Louisiana, and now living in Occupied Portland. She used to work as a geriatric nurse, but three years ago, she hurt her back so bad on the job that she couldn’t work anymore. The hospital gave her $14,000 to live off of for the rest of her life and then pawned her off on the state welfare bureaucracy, because they could, and the state welfare bureaucracy gave her the usual waiting time of forever, because they could. (They stay paid no matter how they act, and where else is she going to go?) When the money ran out, she got some help from her church, and when that ran out, she started living in her car. Which is cramped, and unpleasant, but sometimes safer and easier than trying to find people to put you up, and certainly safer than living on the streets.

For example, Contia Orsby is a 58 year old black woman, who has spent most of her life helping sick people and, as far as I know, never did any real harm to anybody. She’s originally from Louisiana, and now living in Occupied Portland. She used to work as a geriatric nurse, but three years ago, she hurt her back so bad on the job that she couldn’t work anymore. The hospital gave her $14,000 to live off of for the rest of her life and then pawned her off on the state welfare bureaucracy, because they could, and the state welfare bureaucracy gave her the usual waiting time of forever, because they could. (They stay paid no matter how they act, and where else is she going to go?) When the money ran out, she got some help from her church, and when that ran out, she started living in her car. Which is cramped, and unpleasant, but sometimes safer and easier than trying to find people to put you up, and certainly safer than living on the streets.

Until July 4, 2008, when a pair of Gangsters in Blue decided to roll up on her and search her as part of a welfare check.

Here’s how they looked out for her welfare–by stealing her car and throwing her out on the street.

On July 4, Portland Police Bureau Officers Joseph Cook and Judy McFarlane rolled up on

Orsby at 2 pm as she was slumped in her car outside an apartment complex on SE

122nd. They searched Orsby and found a pair of brass knuckles in her pocket, which she

claimed she was using as a key ring. The officers charged Orsby with having a concealed

weapon, driving with a suspended license, and driving without insurance. Instead of

taking her to jail, they towed her car, handed her the citations and drove off, leaving her

homeless on the street.

All three charges against Orsby were thrown out last Thursday, September 11, after

the district attorney’s office declined prosecution.

—Matt Davis, Portland Mercury (2008-09-18): Towing the Line:

Cops Take Car, Leaving Older Disabled Woman Homeless

In real life, outside of statist power-trip La La Land, if you fuck something up that doesn’t belong to you, for no good reason, you pay for it. Normally, if a pair of gang-bangers rolled up you and rousted you out of your car, against your will, when you weren’t doing anything at all to harm a single living soul, sanctimoniously claiming it was for your own good,

then searched you, and rifled through your papers, then demanded to know why you were carrying a pair of brass knuckles (as if it mattered–if she were carrying them for her own protection, what’s wrong with that?), then called you a liar and declared your papers insufficient justification for your existence, and then, finally, used all this as an excuse to jack your car and threaten you with a fine you can’t pay or forced confinement in a jail–if they did all this, I say, and they got caught out, those gangsters would be in jail and they would be expected to return the car they’d stolen and pay for what they did out of their own pockets. But because these gang-bangers were Gangsters in Blue, and because they acted with the biggest gangster of all, the State Law-and-Order Protection Racket, at their back, when these charges were dropped, and the whole thing declared a big mistake, Portland Police Bureau Officers Joseph Cook and Judy McFarlane are virtually guaranteed never to suffer a single adverse consequence for their obvious, pointless, and cruel violation of poor people’s property rights. And neither they nor their bosses, the collaborationist puppet government of Occupied Portland, will do anything to make it right, beyond an Oops, our bad

; in fact, they feel perfectly happy to force Contia Orsby to pay hundreds of dollars that she doesn’t have, just to recover her own property from the fence they sold it to.

CONTIA ORSBY, 58, stood with the deacon of her church on the lot of Andy’s Towing on SE 82nd last Friday afternoon, September 12. She was there to retrieve her all-white 1988 four-door Cadillac Brougham, bought five years ago for $4,700 from a used car lot up the street, during more fortunate times. It had briefly been her home, until police confiscated the vehicle on Independence Day.

Orsby had already handed over $400 to the towing firm, and $225 to get a release for her vehicle from the courthouse. Still owing $600 more, the manager of the towing company had generously cut her a deal.

He told me if I promised him $200 from my next disability check, I could come and get the car today,

she said.

Too bad, because the towing firm had lost the keys: They called a locksmith, and tried to charge Orsby for the cost of cutting some new ones.

We’re doing you a favor,

the manager told her. We’re only supposed to keep the car, technically, for 30 days.

Orsby refused to pay for the locksmith, and ultimately, the towing company handed over her car. Her deacon, Albert Woods, from the Emmanuel Church of God in Christ United on NE 30th, had taken the afternoon off to drive Orsby to the towing lot. He shook his head.

They wouldn’t treat her like this if she were the president, that’s for sure,

he said.

—Matt Davis, Portland Mercury (2008-09-18): Towing the Line:

Cops Take Car, Leaving Older Disabled Woman Homeless

It’s true, and the management were certainly acting like dicks to her. But why can they get away with that kind of behavior? Simply because, as the fence for the cars stolen by the State, they have no reason to care about making things easy on you, or Contia Orsby, or anybody else. Why should they? They get most or all of their business from people like the President, not from people like you–people who are part of the State, a monopoly outfit which pays for itself through extortion rackets and robbery just like the screwjob they pulled on Contia Orsby, and who use their positions of political power to evade taking any responsibility for their own violations of the liberty and security that their cops and their so-called Law and Order

are supposed to protect. Like any other fence, this one doesn’t much care about your life or your livelihood, and he doesn’t much care about helping you recover your stolen property. He serves the racket, not you. Do away with the racket, and you’ll do away with the other petty criminals and hangers-on that take their cuts from the loot.

You can contact the Portland Police Bureau to let them know what you think of their welfare checks

and of Joseph Cook and Judy McFarlane’s efforts to force poor people out onto the street, at:

Portland Police Bureau

1111 S.W. 2nd Avenue

Portland, Oregon 97204

You can send comments to Chief Rosie Sizer at chiefsizer@portlandpolice.org, or call her office at (503) 823-0000, or send a FAX to (503) 823-0342.

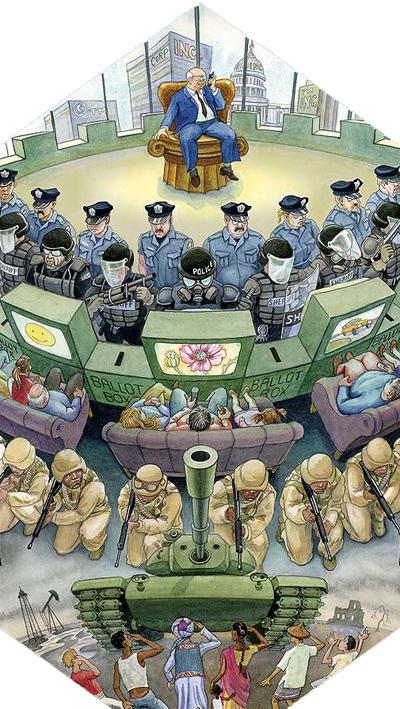

I’ve said before that urban poverty as we know it is exclusively the creation of the State, and now I’ll add that this is especially true of homelessness as we know it. I don’t mean to claim that in a genuinely free society, with freed people, freed labor, and freed markets, with freedom for the poor and with no political patronage for the rich, that nobody would ever have to scratch by on short money. And I don’t mean that nobody would ever have to live without a house or apartment for a while due to short money. That would be a lot less common if people were free to scratch money together through creative hustling, to lower their fixed costs of living, and to join together for voluntary, neighborhood-based mutual aid, without having to bear the burdens of State-imposed taxes, usury laws, vagrancy laws, prohibition laws, border laws, business license laws, zoning laws, business laws, professional licensing laws, building codes, health and hygiene codes, fines and forfeitures, eminent domain land grabs and politicized development

rackets, welfare bureaucrats, social workers and cops, and the rest of the whole taxation-and-regimentation government apparatus that constantly robs, cages, and busybodies poor people, all while sanctimoniously declaring that it’s all For Their Own Good, like one big welfare check

on the Contia Orsbys of the world. If people were free of all that, hard times would be a lot less hard, but nobody can realistically promise an end to all tough times or shitty situations, whether by Anarchy or by any other means. Some people might lose their jobs, some people might go hungry, and some people might lose the roof over their heads. But homelessness as we know it — as a long-term, self-reinforcing downward spiral of destitution, in which hard times force people out onto the street, exposed to the elements and to danger from other people, or into overcrowded and dangerous institutional shelters — only exists because the State — the city and state governments, in particular — has a fixed policy of repeatedly sending gangs of thuggish police and busybody case-workers and bureaucratic inspectors around to hassle so-called vagrants

; to subject them to constant citations, fines, arrests, and pointless humiliations; to roust them up out of any place that they settle in to stay; to violate their rights to homestead unused land, and to obstruct, invade, trash, or tow away any transitional, intermediate, or otherwise informal sort of shelter that poor people might try to arrange for themselves. It’s one thing not to be able to afford the sorts of houses and apartments and long-term rooming arrangements that journalists and economists and sociologists count as homes

for the purposes of statistics and public debate. It’s quite another to be thrown out on the street without any kind of reliable shelter, and we all ought to recognize that as the child of the State. In that sense, all homelessness is forced homelessness, and all homeless people are the internally displaced

refugees of the State’s ongoing War on Poverty and campaigns of economic cleansing.

But a rich man he says that Pig Hollow must go:

It’s a place where the crooks rendezvous.

But don’t you suppose if they burned down the bank,

They might flush a scoundrel or two?

And don’t you suppose if a bum with a torch

Set fire to some big fancy hall,

The cops’d come down like a blood-thirsty hound

And flat nail his hide to the wall?

It seems like the laws are all made for the rich;

They’ve got you, boys, win, lose, or draw.

Try as you may to keep out of the way,

You just get burned out by the law.

— Utah Phillips, Pig Hollow, on The Telling Takes Me Home (1975)

That’s how Contia Orsby got served and protected by Portland cops: by being thrown out of the car that is her home, on the excuse of a bunch of petty so-called crimes

with no identifiable victims, having it towed away, and then, months later, when the State magnanimously allowed her to be left the hell alone, by being forced to pay to get it back even though she was never convicted of any crime, victimless or otherwise. If you're baffled that cops could get away with these kind of outrages, it may help to remember that in a lot of American cities, there just is no such thing as a civil police force. What we have would be better described as thuggish paramilitary units occupying what they regard as hostile territory: like any occupying force, the people they go after the first and the hardest are generally the people who are most vulnerable, and like any other occupying force there is no real recourse for anything they may choose to do on their patrols. Here as elsewhere, they are going to serve and protect

us, whether we want them to or not, and if we don't like it then they've got plenty of guns and clubs and cuffs to make sure they can protect the hell out of us all anyway.

See also:

For example,

For example,