Steal This Cartoon

Over at Austro-Athenian Empire, Roderick recently mentioned a couple particularly bizarre attempts to use Intellectual Protectionism in the service of chickenshit (parrot-shit?) speech-control. I have a story about that, too, actually.

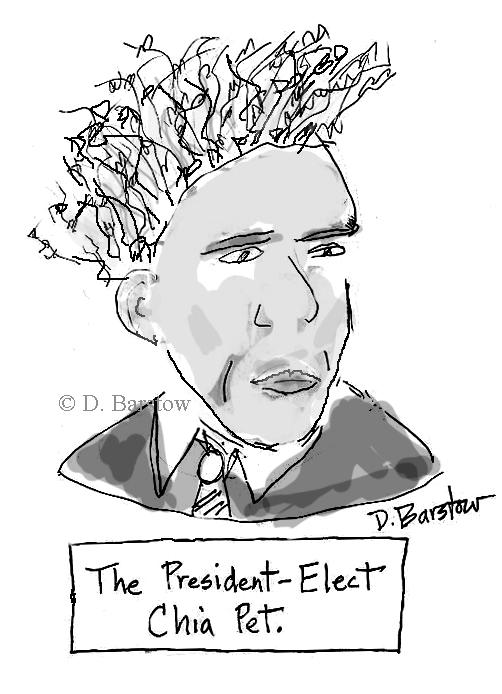

A few days ago over at Alas, A Blog, Jeff Fecke and Mandolin each put up a couple of posts featuring images of a couple racist-ass cartoons by Donna Barstow (1, 2). Specifically, these:

Hey everybody! The entire country of Mexico is dirty, dangerous, and poor! Also, they give us deadly plagues!

Hey everybody! … Um. Wait. Somebody remind me what the hell the point of this cartoon is, again?

The reason I’m using the image of these cartoons here is for the purpose of commenting on them. Specifically, for the purpose of demonstrating the fact that both cartoons are crudely racist; they also just are terrible cartoons. The first one — which is just a bullet list of standard Anglo disdain for Mexico as poor and dirty and dangerous, with a bit of topical scapegoating and racist-ass panic over the flu tossed in for good measure, all of it awkwardly shoe-horned into a joke through an awkward pastiche of insurance advertising slogans — isn’t especially funny. The second one is not merely unfunny, but, as far as I can make out, in fact is so pointless as to defy classification as even attempted humor. O.K.; yes; I understand that Barack Obama is black, and that, like many black people, he has hair that tends to be more kinky than the kind of hair stereotypical of white people. Is there a punchline here? (Really, seriously, if anyone can figure out what the point of it is, let me know. I’m seriously tempted to view it as avant-garde commentary by the deed, bringing Dada to the world of editorial cartooning in order to undermine the bourgeois affectation that cartoons need to have points

or make sense.

)

I’m also reposting these here because shortly after the posts went online, Donna Barstow showed up in the comments to invoke copyright law, accuse Alas of thieving

, and to threaten the folks at Alas with complaints to their web host or legal action in an attempt to intimidate them into taking down the posts. As it happens, I also got a nasty-gram from Ms. Barstow, because Alas is one of the blogs syndicated at Feminist Blogs, and so the posts with the images appeared there too. So I received the following demand and threat from Ms. Barstow last Thursday:

From: Donna Barstow Cartoons <donnabarstow@sbcglobal.net>

To: Feminist Blogs Web Admin

Subject: take my copyrighted cartoon off your site immediately

Date: 4/30/2009 12:53 AMDear Feminist Blogs,

I’m a feminist. I’ve written 2 cartoon books for women. I am one of only 3 women out of 60 editorial cartoonists. However, I do not STEAL from other people, and I hope you don’t either. http://www.amptoons.com/blog/archives/2009/04/29/another-racist-cartoon-by-editorial-cartoonist-donna-barstow/ And frankly, I’m shocked that a FEMINIST blog would simply take for granted that anything published by the amptoons crazies would have any truth at all!!! You did no research or even ask me, and you assume it’s all right to call a person (in this case a woman) a racist and ruin her reputation???? This is a hate crime on your part, and you will not be happy if I have to contact your server.

I own all rights to the cartoon and the idea. I have already contacted amptoons server to have it taken down tomorrow, and they will get a warning.

Please refer to DMCA copyright infringement requirements at http://www.softlayer.com/legal.html before you willfully abuse copyrighted work, defame and harass innocent people. Please remove my cartoon immediately. Thank you.

Kind Regards,

Donna Barstow

And look for me all week in Slate! (all Editorial cartoons)

Why I Did It (some Editorial cartoons)

Donna Barstow Cartoons (no Editorial cartoons, but still good)

Barry Deutsch, who runs Alas, will have to choose his own course. As for Feminist Blogs, though, the answer is: Absolutely not. I will do no such thing.

As it happens, I don’t think Ms. Bartsow has a legal leg to stand on — the use of the cartoons for the purpose of commentary, especially for non-commercial educational purposes, is well within the realm of fair use. But more to the point, even if she did have a legal leg to stand on, that would only be an indictment of such a ridiculous, tyrannical and dialogue-stifling law. Barstow is not losing one penny from the reprinting of cartoons in the context of a commentary on their contents; the cartoons were and are being given away for free on the Internet to anyone who wanted to look at them. Nobody is trying to appropriate credit for the cartoons or trying to pass off her racist-ass cartoons as their own; the whole point of the posts is to point out that they were drawn by somebody else, and that that somebody else is expressing some crude racism. Barstow’s only complaint here, the only thing this stealing

amounts to, is the fact that the cartoons are being used for a purpose that Barstow doesn’t like — specifically, that they are being used as visible evidence in an effort to criticize her work and to support claims about the character of her work which Barstow disagrees with, and finds insulting. Her threats are an explicit attempt to use Intellectual Protectionism as a tool of censorship, to attack those who disagree with her as thieves,

and to coercively silence criticism of her work. That is nothing more than thuggery in a three-piece suit, and Ms. Barstow ought to be ashamed of herself.

I am also posting all this, not only to talk about the story itself, but to encourage you to talk about it, too. If silencing critics is what she wants to achieve, I would like Donna Barstow to find out that it will not work. I encourage anyone and everyone who supports free speech, and who believes that people who draw racist-ass cartoons oughtn’t to be able to go around threatening their critics into silence, to repost this post, or to write a post of your own that uses Donna Barstow’s racist-ass comics as evidence in the course of a critical commentary on the content of those comics, and that discusses her attempts to use Intellectual Protectionism laws as a tool to censor the critics of her work.

Consider it a form of direct action against law-waving bullies and for vigorous, open debate. People who act like this need to know that their would-be victims will not be silenced. And the more that they become convinced that these attempts to stifle criticism will reliably produce exactly the opposite of their desired outcome, with so many people reposting the criticism that any attempt to shut it down will be swamped by sheer numbers, the less likely they are to imagine that it could possibly be a good idea.