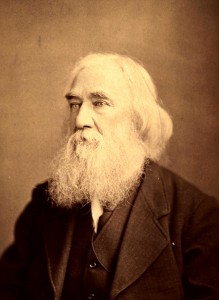

To-day — 19 January 2013 — is the 205th birthday of the militant abolitionist, philosopher and individualist anarchist Lysander Spooner (b. 19 January 1808, Athol, Massachusetts; d. May 14, 1887, Boston, Massachusetts). In honor of his life and work, the Ministry of Culture in this secessionist republic of one is happy to once again mark to-day as Lysander Spooner Day.

This is from Spooner’s first letter to Thomas F. Bayard: Challenging His Right — and That of All the Other So-Called Senators and Representatives in Congress — To Exercise Any Legislative Power Whatever Over the People of the United States.

1. No man can delegate, or give to another, any right of arbitrary dominion over himself; for that would be giving himself away as a slave. And this no one can do. Any contract to do so is necessarily an absurd one, and has no validity. To call such a contract a !!!@@e2;20ac;2dc;Constitution,' or by any other high-sounding name, does not alter its character as an absurd and void contract.

2. No man can delegate, or give to another, any right of arbitrary dominion over a third person; for that would imply a right in the first person, not only to make the third person his slave, but also a right to dispose of him as a slave to still other persons. Any contract to do this is necessarily a criminal one and therefore invalid. To call such a contract a !!!@@e2;20ac;2dc;Constitution' does not at all lessen its criminality, or add to its validity.

These facts, that no man can delegate, or give away, his own natural right to liberty, nor any other man’s natural right to liberty, prove that he can delegate no right of arbitrary dominion whatever–or, what is the same thing, no legislative power whatever–over himself or anybody else, to any man, or body of men.

. . . All this pretended delegation of legislative power—that is, of a power, on the part of the legislators, so-called, to make any laws of their own device, distinct from the law of nature—is therefore an entire falsehood; a falsehood whose only purpose is to cover and hide a pure usurpation, by one body of men, of arbitrary dominion over other men.

. . . For all the reasons now given, and for still others that might be given, the legislative power now exercised by Congress is, in both law and reason, purely personal, arbitrary, irresponsible, usurped dominion on the part of the legislators themselves, and not a power delegated to them by anybody.

Yet under the pretense that this instrument gives them the right of an arbitrary and irresponsible dominion over the whole people of the United States, Congress has gone on, for ninety years and more, filling great volumes with laws of their own device, which the people at large have never read, nor even seen nor ever will read or see; and of whose legal meanings it is morally impossible that they should ever know anything. Congress has never dared to require the people even to read these laws. Had it done so, the oppression would have been an intolerable one; and the people, rather than endure it, would have either rebelled, and overthrown the government, or would have fled the country. Yet these laws, which Congress has not dared to require the people even to read, it has compelled them, at the point of the bayonet, to obey.

And this moral, and legal, and political monstrosity is the kind of government which Congress claims that the Constitution authorizes it to impose upon the people.

Sir, can you say that such an arbitrary and irresponsible dominion as this, over the properties, liberties, and lives of fifty millions of people–or even over the property, liberty, or life of any one of those fifty millions–can be justified on any reason whatever? If not, with what color of truth can you say that you yourself, or anybody else, can act as a legislator, under the Constitution of the United States, and yet be an honest man?

. . . I trust I need not suspect you, as a legislator under the Constitution, and claiming to be an honest man, of any desire to evade the issue presented in this pamphlet. If you shall see fit to meet it, I hope you will excuse me for suggesting that — to avoid verbiage, and everything indefinite — you give at least a single specimen of a law that either heretofore has been made, or that you conceive it possible for legislators to make–that is, some law of their own device–that either has been, or shall be, really and truly obligatory upon other persons, and which such other persons have been, or may be, rightfully compelled to obey.

If you can either find or devise any such law, I trust you will make it known, that it may be examined, and the question of its obligation be fairly settled in the popular mind.

But if it should happen that you can neither find such a law in the existing statute books of the United States, nor, in your own mind, conceive of such a law as possible under the Constitution, I give you leave to find it, if that be possible, in the constitution or statute book of any other people that now exist, or ever have existed, on the earth.

If, finally, you shall find no such law, anywhere, nor be able to conceive of any such law yourself, I take the liberty to suggest that it is your imperative duty to submit the question to your associate legislators; and, if they can give no light on the subject, that you call upon them to burn all the existing statute books of the United States, and then to go home and content themselves with the exercise of only such rights and powers as nature has given to them in common with the rest of mankind.

–Lysander Spooner, A Letter to Thomas F. Bayard (Boston, May 22, 1882)

And this is from No. 6 (The Constitution of No Authority

) of his most famous pamphlet series, No Treason

The payment of taxes, being compulsory, of course furnishes no evidence that any one voluntarily supports the Constitution. . . . [T]his theory of our government is wholly different from the practical fact. The fact is that the government, like a highwayman, says to a man: Your money, or your life. And many, if not most, taxes are paid under the compulsion of that threat.

The government does not, indeed, waylay a man in a lonely place, spring upon him from the road side, and, holding a pistol to his head, proceed to rifle his pockets. But the robbery is none the less a robbery on that account; and it is far more dastardly and shameful.

The highwayman takes solely upon himself the responsibility, danger, and crime of his own act. He does not pretend that he has any rightful claim to your money, or that he intends to use it for your own benefit. He does not pretend to be anything but a robber. He has not acquired impudence enough to profess to be merely a "protector," and that he takes men's money against their will, merely to enable him to "protect" those infatuated travellers, who feel perfectly able to protect themselves, or do not appreciate his peculiar system of protection. He is too sensible a man to make such professions as these. Furthermore, having taken your money, he leaves you, as you wish him to do. He does not persist in following you on the road, against your will; assuming to be your rightful "sovereign," on account of the "protection" he affords you. He does not keep "protecting" you, by commanding you to bow down and serve him; by requiring you to do this, and forbidding you to do that; by robbing you of more money as often as he finds it for his interest or pleasure to do so; and by branding you as a rebel, a traitor, and an enemy to your country, and shooting you down without mercy, if you dispute his authority, or resist his demands. He is too much of a gentleman to be guilty of such impostures, and insults, and villanies as these. In short, he does not, in addition to robbing you, attempt to make you either his dupe or his slave.

–Lysander Spooner, No Treason, no. 6: The Constitution of No Authority (1870)

And this is from the end of the same pamphlet:

Inasmuch as the Constitution was never signed, nor agreed to, by anybody, as a contract, and therefore never bound anybody, and is now binding upon nobody; and is, moreover, such an one as no people can ever hereafter be expected to consent to, except as they may be forced to do so at the point of the bayonet, it is perhaps of no importance what its true legal meaning, as a contract, is. Nevertheless, the writer thinks it proper to say that, in his opinion, the Constitution is no such instrument as it has generally been assumed to be; but that by false interpretations, and naked usurpations, the government has been made in practice a very widely, and almost wholly, different thing from what the Constitution itself purports to authorize. He has heretofore written much, and could write much more, to prove that such is the truth. But whether the Constitution really be one thing, or another, this much is certain – that it has either authorized such a government as we have had, or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case, it is unfit to exist.

–Lysander Spooner, Appendix to No Treason, no. 6: The Constitution of No Authority (1870)

See also: