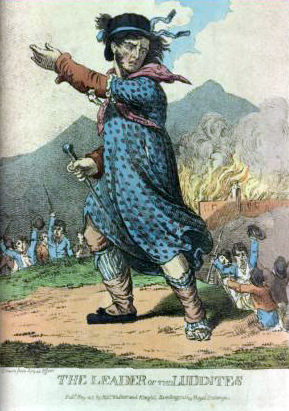

King Ludd’s throne

Over at LewRockwell.com Blog, Karen De Coster recently posted about Ford’s Camaçari assembly plant in Brazil, taking it as an opportunity to complain about the way union thugs [sic] run Ford’s business

in Estadounidense assembly plants, and how Ford may have trouble introducing a similar manufacturing model in U.S. plants because the UAW is hesitant. Other than noting that the stories are little more than a couple of glorified Ford Motor Company press releases, passed off as journalism by the Detroit News, I don’t have anything in particular to say about the set-up Camaçari, or for that matter about Ford Motor Company or the UAW. (I consider the both of them to be brontosaurs of state capitalism — massive, slow, stupid, and probably doomed to extinction.) But I do want to mention De Coster’s boilerplate complaints against labor unions, and what they presuppose.

De Coster, like lots of other anti-union libertarians, claims that unions are economically harmful because they’re toxic to efficiency and flexibility. The idea is that organized workers will tend to use their organization to oppose advances like automation, technological upgrades, flexible job duties, and reorganization of processes for greater efficiency. Partly because union contracts tend to preserve old job descriptions in amber, to better mark off each worker’s turf, and partly because organized workers will use their coordinated bargaining power to oppose anything that reduces organized workers’ hours or introduces new, not-yet-unionized (or differently-unionized) jobs into the shop. I don’t necessarily find this complaint very persuasive. But. hell, let’s grant most of it, for the sake of argument. Suppose that a union like the UAW does tend to block upgrades for greater efficiency and flexibility. If that’s true, why is it true? Because the unionized workers don’t own the means of production.

It’s no surprise that there would be conflicts between the interests of the workers and the interests of the boss and board when it comes to innovation in shop-floor technology or processes. For a wage laborer, sometimes new technology and new processes mean easier and better work to do; often they mean that your hours will be cut or you’ll lose your job entirely. In any case they will be deployed and integrated into the flow of work according to what the boss finds most useful; they may very well result in you, as a wage laborer, getting stuck with speed-ups or harder work.

None of this is a decisive argument against innovations in shop-floor technology or processes; sometimes things have to change, and change can be hard. But it is a natural source of conflicts between labor and capital. When workers are organized — and when the goals of the organized workers are limited to eking out the highest hourly wages and benefits, the most reliable hours, and the easiest conditions, that they can get within the existing ownership structure and business model of the corporation, through stage-managed labor actions, back-room negotiations with the boss, and multiyear fixed contracts, while the boss and the board keep ahold of final control over conditions on the shop-floor and most or all of the residual profits from any efficiency improvements, what you’ll tend to see is a perpetual collision between a small but powerful coterie of managers and owners, who have every reason to try to shove new processes and technologies down their employees’ throats, to the extent that they can get away with it, and a consolidated mass of workers who have little reason to care about starving themselves lean

in order to fatten profits that don’t go to them. Why should workers want to do more work faster, or to take on more flexible job descriptions, if they only stand to lose hours or subjected to speed-ups for their trouble? Both workers’ livelihoods and process efficiency get caught in the crossfire.

But the business model offered by that small coterie, and the union organizing model offered by that consolidated mass aren’t the only business models or union organizing models on offer, and the fact that they are so prevalent in American heavy industry today is the direct result of a series of political decisions and a system of government economic regimentation that allowed that business model and that organizing model to shove alternatives out of the way. Alternatives like that offered by the Industrial Workers of the World and other state-free wildcat unions, which called not for a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work,

but rather for abolishing the wage system, and replacing it with worker ownership of the means of production, coordinated through decentralized, participatory unions.

If the workers themselves jointly own the means of production, then the union has no reason to sandbag efficiency upgrades: if organized workers keep most or all of the residual profits then they have every reason to want more flexible job descriptions, more efficient processes, and greater integration of labor-saving technology. Maybe it’ll mean fewer hours of labor; but since the worker keeps the increased profits, the reduction of hours is a net gain rather than an economic blow. And if workers make agreements amongst themselves as to the conditions of their own labor, they have little reason to want their specific role in the shop written on tablets of stone, and little reason to fear new processes or technology which they are free to take up or not to take up on their own terms and at their own pace, rather than as dictated by a chain of command.

De Coster trashes the UAW for responding to the incentives that the wage system presents for their workers; but rather than getting rid of the UAW, the better solution would be to quit the griping and change the incentives. There is no natural connection between labor organizing, on the one hand, and Luddism or labor-contract sclerosis, on the other. It’s a matter of the artificially rigidified economics of state-subsidized corporate capitalism, and the artificially narrowed vision of the state-patronized establishmentarian labor movement. The only reason that centralized, state capitalist corporations like Ford find themselves confronting top-heavy establishmentarian unions like the UAW over efficiency upgrades is that the both of them have conspired — with the active patronage and regulatory encouragement of the United States federal government — to sustain a business model in which the vast majority of workers have no stake in, and thus little or no natural interest in, the efficiency of the shop, and little or no control over how new processes or new technology, if implemented, will affect the hours and conditions of their labor.

The solution isn’t more ruthless corporate union busting; the solution is to strike at the root of the problem, by abolishing the government economic regimentation that sustains both establishmentarian unionism and state capitalism. If the UAW is cut free from the smothering patronage of the State, and becomes what union so often were before the Wagner/Taft-Hartley era — a wildcat industrial union, free to play hardball and free to set its sights not just on negotiated wage and benefits settlements, but on the unionized workers themselves owning the shop, the machine and the tools — then King Ludd’s throne will crumble out from under him, and you’ll soon start to see unions that not only accept, but champion innovations in technology and industrial processes. If workers own the shop, why wouldn’t they want to increase their own efficiency? After all, they get to keep the difference.

See also:

- GT 2004-05-01: Free the Unions (and all political prisoners)!

- GT 2008-02-20: Over My Shoulder #41: Paul Buhle on establishmentarian unionism, the decline of labor organizing, and the rise of Labor PAC. From Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland, and the Tragedy of American Labor.

- GT 2005-12-30: Over My Shoulder #4: Paul Buhle's Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland, and the Tragedy of American Labor

- GT 2005-12-09: Over My Shoulder #1 (or: Friday Book-Bragging)