Over My Shoulder #19: Robert Whitaker (2002), Mad in America on metrazol “therapy”

You know the rules; here’s the quote. This week’s reading is from Robert Whitaker’s Mad in America again (see also Over My Shoulder #15, on the early modern English mad doctors). This passage was reading from the ride home from work and the walk home from the bus stop. I wish I had something to say, but it’s really too awful to bear comment. Here’s the quote:

For hospitals, the main drawback with insulin-coma therapy was that it was expensive and time-consuming. By one estimate, patients treated in this maner received

100 timesthe attention from medical staff as did other patients, and this greatly limited its use. In contrast, metrazol convulsive therapy, which was introduced into U.S. asylums shortly after Sakel’s insulin treatment arrived, could be administered quickly and easily, with one physician able to treat fifty or more patients in a single morning.Although hailed as innovative in 1935, when Hungarian Ladislas von Meduna first announced its benefits, metrazol therapy was actually a remedy that could be traced back to the 1700s. European texts from that period tell of using camphor, an extract from the laurel bush, to induce seizures in the mad. Meduna was inspired to revisit this therapy by speculation, which wasn’t his alone, that epilepsy and schizophrenia were antagonistic to each other. One disease helped to drive out the other. Epileptics who developed schizophrenia appeared to have fewer seizures, while schizophrenics who suffered seizures saw their psychosis remit. If that was so, Meduna reasoned, perhaps he could deliberately induce epileptic seizures as a remedy for schizophrenia.

With faint hope and trembling desire,he later recalled,the inexpressible feeling arose in me that perhaps I could use this antagonism, if not for curative purposes, at least to arrest or modify the course of schizophrenia.After testing various poisons in animal experiments, Meduna settled on camphor as the seizure-inducing drug of choice. On January 23, 1934, he injected it into a catatonic schizophrenic, and soon Meduna, like Klaesi and Sakel, was telling a captivating story of a life reborn. After a series of camphor-induced seizures, L. Z., a thirty-three year old man who had been hospitalized for four years, suddenly rose from his bed, alive and lucid, and asked the doctors how long he had been sick. It was a story of a miraculous rebirth, with L. Z. soon sent on his way home. Five other patients treated with camphor also quickly recovered, filling Meduna with a sense of great hope:

I feel elated and I knew I had discovered a new treatment. I felt happy beyond words.As he honed his treatment, Meduna switched to metrazol, a synthetic preparation of camphor. His tally of successes rapidly grew: Of his first 110 patients, some who had been ill as long as ten years, metrazol-induced convulsions freed half from their psychosis.

Although metrazol treatment quickly spread throughout European and American asylums, it did so under a cloud of great controversy. As other physicians tried it, they published recovery rates that were wildly different. One would find that it helped 70 percent of schizophrenic patients. The next wouldfind that it didn’t appear to be an effective treatment for schizophrenia at all but was useful for treating manic-depressive psychosis. Others would find it helped almost no one. Rockland State Hospital in New York announced that it didn’t produce a single recovery among 275 psychotic patients, perhaps the poorest reported outcome in all of psychiatric literature to that time. Was it a totally

dreadfuldrug, as some doctors argued? Or was it, as one physician wrote,the elixir of life to a hitherto doomed race?A physician’s answer to that question depended, in large measure, on subjective values. Metrazol did change a person’s behavior and moods, and in fairly predictable ways. Physicians simply varied greatly in their beliefs about whether that change should be deemed an

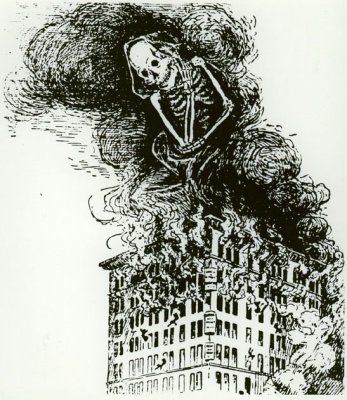

improvement.Their judgment was also colored by their own emotional response to administering it, as it involved forcing a violent treatment on utterly terrified patients.Metrazol triggered an explosive seizure. About a minute after the injection, the patient would arch into a convulsion so severe it could fracture bones, tear muscles, and loosen teeth. In 1939, the New York State Psychiatric Institute found that 43 percent of state hospital patients treated with metrazol had suffered spinal fractures. Other complications included fractures of the humerus, femur, pelvic, scapula, and clavicle bones, dislocations of the shoulder and jaw, and broken teeth. Animal studies and autopsies revealed that metrazol-induced seizures caused hemorrhages in various organs, such as the lungs, kidney, and spleen, and in the brain, with the brain trauma leading to

the waste of neuronsin the cerebral cortex. Even Meduna acknowledged that his treatment, much like insulin-coma therapy, madebrutal inroads into the organism.We act with both methods as with dynamite, endeavoring to blow asunder the pathological sequences and restore the diseased organism to normal functioning … beyond all doubt, from biological and therapeutic points of view, we are undertaking a violent onslaught with either method we choose, because at present nothing less than such a shock to the organism is powerful enough to break the chain of noxious processes that leads to schizophrenia.

As with insulin, metrazol shock therapy needed to be administered multiple times to produce the desired lasting effect. A complete course of treatment might involve twenty, thirty, or forty or more injections of metrazol, which were typically given at a pace of two or three a week. To a certain degree, the trauma so inflicted also produced a change in behavior similar to that seen with insulin. As patients regained consciousness, they would be dazed and disoriented–Meduna described it as a

confused twilight state.Vomiting and nausea were common. Many would beg doctors and nurses not to leave, calling for their mothers, wanting tobe hugged, kissed and petted.Some would masturbate, some would become amorous toward the medical staff, and some would play with their own feces. All of this was seen as evidence of a desired regression to a childish level, of aloss of control of the higher centresof intelligence. Moreover, in this traumatized state, manyshowed much greater friendliness, accessibility, and willingness to cooperate,which was seen as evidence of their improvement. The hope was that with repeated treatments, such friendly, cooperative behavior would become more permanent.The lifting in mood experienced by many patients, possibly resulting from the release of stress-fighting hormones like epinephrine, led some physicians to find metrazol therapy particularly useful for manic-depressive psychosis. However, as patients recovered from the brain trauma, they typically slid back into agitated, psychotic states. Relapse with metrazol was even more problematic than with insulin therapy, leading numerous physicians to conclude that

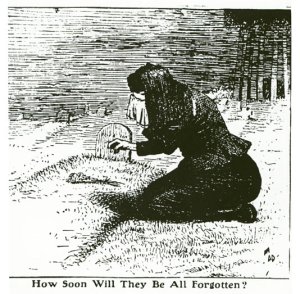

metrazol shock therapy does not seem to produce permanent and lasting recovery.Metrazol’s other shortcoming was that after a first injection, patients would invariably resist another and have to be forcibly treated. Asylum psychiatrists, writing in the American Journal of Psychiatry and other medical journals, described how patients would cry, plead that they

didn’t want to die,and beg themin the name of humanityto stop the injections. Why, some patients would wail, did the hospital want tokillthem?Doctor,one woman pitifully asked,is there no cure for this treatment?Even military men who had bornewith comparative fortitude and bravery the brunt of enemy actionwere said to cower in terror at the prospect of a metrazol injection. One patient described it as akin tobeing roasted alive in a white-hot furnace; anotheras if the skull bones were about to be rent open and the brain on the point of bursting through them.The one theme common to nearly all patients, Katzenelbogen concluded in 1940, was a feelingof being excessively frightened, tortured, and overwhelmed by fear of impending death.The patients’ terror was so palpable that it led to speculation whether fear, as in the days of old, was the therapeutic agent. Said one doctor:

No reasonable explanation of the action of hypoglycemic shock or of epileptic fits in the cure of schizophrenia is forthcoming, and I would suggest as a possibility that as with the surprise bath and the swinging bed, the

modus operandimay be the bringing of the patient into touch with reality through the strong stimulation of the emotion of fear, and that the intense apprehension felt by the patient after an injection of cardiazol [metrazol] and so feared by the patient, may be akin to the apprehension of a patient threatened with the swinging bed. The exponents of the latter pointed out that fear of repetition was an important element in its success.Advocates of metrazol were naturally eager to distinguish it from the old barbaric shock practices and even conducted studies to prove that fear was not the healing agent. In their search for a scientific explanation, many put a Freudian spin on the healing psychology at work. One popular notion, discussed by Chicago psychotherapist Roy Grinker at an American Psychiatric Association meeting in 1942, was that it put the mentally ill through a near-death experience that was strangely liberating.

The patient,Grinker said,experiences the treatment as a sadistic punishing attack which satisfies his unconscious sense of guilt.Abram Bennett, a psychiatrist at the University of Nebraska, suggested that a mental patient, by undergoingthe painful convulsive therapy,hasproved himself willing to take punishment. His conscience is then freed, and he can allow himself to start life over again free from the compulsive pangs of conscience.As can be seen by the physicians’ comments, metrazol created a new emotional tenor within asylum medicine. Physicians may have reasoned that terror, punishment, and physical pain were good for the mentally ill, but the mentally ill, unschooled in Freudian theories, saw it quite less abstractly. They now perceived themselves as confined in hospitals where doctors, rather than trying to comfort them, physically assaulted them in the most awful way. Doctors, in their eyes, became their torturers. Hospitals became places of torment. This was the beginning of a profound rift in the doctor-patient relationship in American psychiatry, one that put the severely mentally ill ever more at odds with society.

Even though studies didn’t provide evidence of any long-term benefit, metrazol quickly became a staple of American medicine, with 70 percent of the nation’s hospitals using it by 1939. From 1936 to 1941, nearly 37,000 mentally ill patients underwent this treatment, which meant that they received multiple injections of the drug.

Brain-damaging therapeutics–a term coined in 1941 by a proponent of such treatments–were now being regularly administered to the hospitalized mentally ill, and being done so against their will.–Robert Whitaker, Mad in America: Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and the Enduring Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill (2002), pp. 91–96.

It’s revealed in a footnote (and mentioned later in the book) that the proponent who coined the term brain-damaging therapeutics

was none other than Walter Freeman, the pioneer of the icepick lobotomy, in Brain-Damaging Therapeutics, Diseases of the Nervous System 2 (1940): 83.