Bill of Rights Day festivities

I’ve been thinking for a while that I ought to start a feature leading up to the (upcoming) 5th anniversary of Geekery Today, called Dumb Things I’ve Said.

The basic idea being that anyone who spends five years writing regularly on controversial topics is likely to change their views over time, and it’s better to spend your commemorative anniversary posts hammering out your own errors than clapping yourself on the back, because you’ve probably said things you later ended up thinking were pretty dumb. I’m no exception, and what I wrote a couple years ago in belated recognition of Bill of Rights Day

is a case in point. I doubt that I’ll actually start the feature, but that won’t keep me from ragging on myself for today, at least.

It’s been 214 years today — December 15th — since the first ten amendments, commonly known as the Bill of Rights,

were scribbled onto the end of the United States Constitution by order of the several states and the Congress of the United States. Folks with too much time on their hands have dubbed it Bill of Rights Day

and think you ought to celebrate the grand legacy of those ten amendments. A couple years ago, I took the opportunity of the 212th anniversary to sing the praises of the Bill of Rights, to bemoan the erosion of some of their traditional protections, and hope that a brighter day would dawn soon. It was a bunch of nonsense, and I should have known that it was at the time, but it took me a while to really see through the dust that the canonical fairy-tales about legal history kick up.

Not surprisingly, I had started doubting the usefulness of leaning on the Constitution when I became an anarchist. But old cognitive habits die hard, and it wasn’t until last year, when I really started reading about William Lloyd Garrison and the rest of the disunionist abolitionists, that I began to feel anti-constitutionalism in any serious way, and it was largely through the Garrisonians that I came to realize the importance of making your arguments from moral basics rather than from legal hermeneutics. Voting abolitionists, and even Lysander Spooner, insisted on twisting the Constitution every which way they could to avoid the conclusion that it was (1) a pro-slavery alliance, and thus (2) an objective force for evil, the covenant with Death and agreement with Hell

that Garrison denounced. But as interesting as Spooner’s argument was, it was really Garrison that was right about the Constitution (as I think Spooner came to realize later in his career); the important thing wasn’t constitutionality, but justice, which is not subject to legislative fiat. The Garrisonians, because so many of them were fervently religious, talked about a higher law

than the Constitution; that’s partly right, but in a sense it’s also a matter of a lower, more human law; any serious theory of justice has to start from our ordinary claims to justice and dignity, the kind of demands that we ordinarily address to our fellow human beings (don’t attack me without reason, don’t trash my stuff, mind your own business if it’s not hurting you) rather than the ritual incantations that you might utter before a Court (Eighth Amendment, Public Use Clause, penumbral right to privacy, blah blah blah).

But as of a couple years ago my recognition of all this was nowhere near complete, and so my half-complete anti-statism didn’t stop me from singing the Bill of Rights’ praises, piously hoping that other branches of government would force the Bush administration to stick more closely to it, and absurdly describing it as that good old parchment barricade against tyranny.

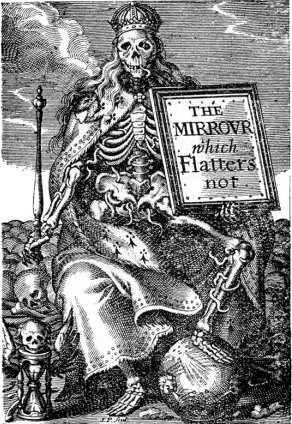

Well, the thing about parchment barricades

is that they don’t hold up very well against pressure. (That’s why you usually want to make barricades out of mud or bricks, at a minimum.) Constitutions don’t protect liberty; people do. Or don’t, which is the legacy the Constitution of the United States leaves us with today. Whatever protections the Bill of Rights was supposed afford white male citizens from the federal government, and whoever those protections were supposed to be extended to in the present day, we have (just to pick a few arbitrarily-selected examples) the FBI spying on us in secret, increasingly arrogant and militant paramilitary police ([1], [2], [3], [4], [5]) occupying our cities, a rampaging global war machine, deliberate and systematic gutting of habeas corpus, and a Justice Department that seems to believe that it can threaten and arrest people for failing to comply with secret laws whose terms they refuse to disclose.

Either the Bill of Rights permits this kind of abuse, in which case it does not deserve the praise of rational people, or it forbids it but is incapable of stopping it, in which case it is useless.

In either case, my whining that this sort of thing oversteps this or that clause is bloody well irrelevant; the problem with invading people’s lives with unwarranted searches and seizures, government-sponsored religious persecution, seizing guns, maintaining a standing war machine, inflicting cruel and unusual punishment, or rounding people up and throwing them in prison forever without charges, is not that they’re unconstitutional; it’s that they’re evil. There may be cases where something is wrong just because it violates some bit of positive law — respect for human life demands that you drive on the side of the road other people drive on, but it’s a matter of arbitrary convention which side that should be — but these are certainly not that sort of case. The right to your own body, to self-defense, to your conscience, to peace and freedom, are prior to any law or compact, the only possible foundation for any just law or legitimate authority at all, and therefore not dependent on the Constitution saying one mumbling word about them.

Human rights don’t need to be written on scraps of paper to be worth defending, and wasting your time and energy wrangling over the right enchantments to invoke The Law on your side is a distraction and a sucker’s bet. I’ll take my rights. You can keep the bill.