Market Anarchists probably haven’t written about the environment as much as we should. But not because we don’t have anything to say about it. When we do address environmental issues specifically, one of the things that I think market Anarchists have really contributed to the discussion are some key points about how ex ante environmental laws, intended to curb pollution and other forms of environmental damage, makes some superficial reforms, but at the expense of creating a legal framework for big polluters to immunize themselves from responsibility for the damage they continue to cause to people’s health and homes, or to the natural resources that people use from day to day;[]. And, also, how legislative environmentalism in general tends to crowd out freed-market methods for punishing polluters and rewarding sustainable modes of production. For a perfect illustration of how legislative environmentalism is actively hurting environmental action, check out this short item in the Dispatches

section of this month’s Atlantic. The story is about toxic mine runoff in Colorado, and describes how statist anti-pollution laws are stopping small, local environmental groups from actually taking direct, simple steps toward containing the lethal pollution that is constantly running into their communities’ rivers — and how big national environmental groups are lobbying hard to make sure that the smaller, grassroots environmental groups keep getting blocked by the Feds.

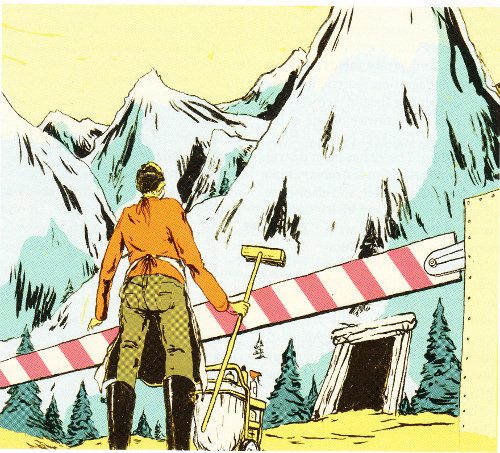

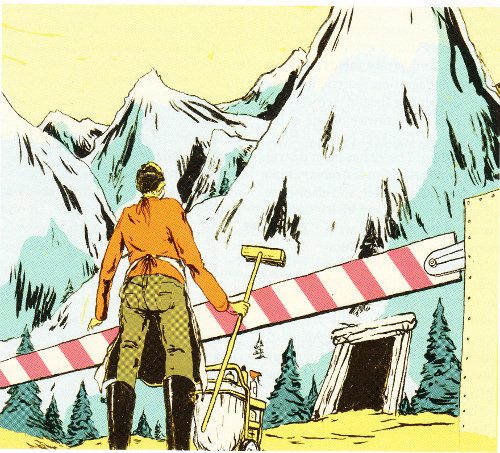

In the surrounding steep valleys, hundreds of defunct silver and gold mines pock

the slopes with log-framed portals and piles of waste rock. When water flows

over the exposed, mineral-laden rock in and around the mines, it dissolves zinc,

cadmium, lead, and other metals. The contaminated water, sometimes

becoming acidic enough to burn skin, then dumps into nearby streams. So-called

acid mine drainage, most of it from abandoned boom-time relics, pollutes an

estimated 12,000 miles of streams throughout the West—about 40 percent of

western waterways.

Near Silverton, the problem became bad enough to galvanize landowners,

miners, environmentalists, and local officials into a volunteer effort to address

the drainage—work that has helped avert a federal Superfund designation and

restore a gold-medal trout population downstream. With a few relatively simple

and inexpensive fixes, such as concrete plugs for mine portals and artificial

wetlands that absorb mine waste, the Silverton volunteers say they could

further reduce the amount of acid mine drainage flowing into local rivers. In

some cases, it would be simple enough just to go up there with a shovel and

redirect the water,

says William Simon, a former Berkeley ecology

professor who has spent much of the past 15 years leading cleanup projects.

But as these volunteers prepare to tackle the main source of the pollution, the

mines themselves, they face an unexpected obstacle—the Clean Water Act.

Under federal law, anyone wanting to clean up water flowing from a hard-rock > mine must bring it up to the act's stringent water-quality standards and take

responsibility for containing the pollution—forever. Would-be do-gooders

become the legal operators

of abandoned mines like those near

Silverton, and therefore liable for their condition.

— Michelle Nijhuis, The Atlantic (May 2010): Shafted

Under anything resembling principles of justice, people ought to be held responsible for the damage they cause, not for the problems that remain after they try to repair damage caused by somebody else, now long gone. But the basic problem with the Clean Water Act, like all statist environmental regulations, is that it isn’t about standards of justice; it’s about compliance with regulatory standards, and from the standpoint of an environmental regulator the important thing is (1) that government has to be able to single out somebody or some group to pigeonhole as the People In Charge of the site; and (2) whoever gets tagged as taking charge

of the site, therefore, gets put on the hook for meeting the predetermined standards, or for facing the predetermined penalties, no matter what the facts of the particular case and no matter the fact that they didn’t do anything to cause the existing damage.[]

The obvious response to this should be to repeal the clause of the Clean Water Act which creates this insane condition, and leave the people with a stake in the community free to take positive action. Unfortunately, the best that government legislators can think of is to pass a new law to legalize it–i.e., to create yet another damn bureaucratic permit

, so that shoestring-budget community groups can spend all their time filling out paperwork and reporting back to the EPA instead. Meanwhile, the State of the Debate being what it is, even this weak, hyperbureaucratic solution is being opposed by the lobbying arms of several national environmental groups:

In mid-October, Senator Mark Udall of Colorado introduced a bill that would

allow such "good Samaritans" to obtain, under the Clean Water Act, special

mine-cleanup permits that would protect them from some liability. Previous

good-Samaritan bills have met opposition from national environmental

organizations, including the Sierra Club, the

Natural Resources Defense Council, and even the

American Bird Conservancy, for whom any weakening of Clean Water Act

standards is anathema. Although Udall's bill is narrower in scope than past

proposals, some environmental groups still say the abandoned-mine problem

should instead be solved with additional regulation of the mining industry and

more federal money for cleanup projects. If you support cleaning up the

environment, why would you support cleaning up something halfway?

asks

Natalie Roy, executive director of the Clean Water Network, a coalition of

more than 1,250 environmental and other public-interest groups. It makes

no sense.

— Michelle Nijhuis, The Atlantic (May 2010): Shafted

All of which perfectly illustrates two of the points that I keep trying to make about Anarchy and practicality.

Statists constantly tell us that, nice as airy-fairy Anarchist theory may be, we have to deal with the real world. But down in the real world, walloping on the tar baby of electoral politics constantly gets big Progressive

lobbying groups stuck in ridiculous fights that elevate procedural details and purely symbolic victories above the practical success of the goals the politicking was supposedly for — to hell with clean water in Silverton, Colorado, when there’s a federal Clean Water Act to be saved! And, secondly, how governmental politics systematically destroys any opportunity for progress on the margin — where positive direct action by people in the community could save a river from lethal toxins tomorrow, if government would just get its guns out of their faces, government action takes years to pass, years to implement, and never addresses anything until it’s just about ready to address everything. Thus Executive Director Natalie Roy, on behalf of More Than 1,250 Environmental And Other Public-Interest Groups, is explicitly baffled by the notion that the people who live by these rivers might not have time to hold out for the decisive blow in winning some all-or-nothing struggle in the national legislature.

The near-term prospects of Udall’s half-hearted legalization bill don’t look good. The conclusion from the Atlantic is despair:

Just a few miles from Silverton, in an icy valley creased with avalanche chutes,

groundwater burbles out of the long-abandoned Red and Bonita gold mine.

Loaded with aluminum, cadmium, and lead, it pours downhill, at 300 gallons a

minute, into an alpine stream. The Silverton volunteers aren't expecting a

federal windfall anytime soon—even Superfund-designated mine sites have

waited years for cleanup funding, and Udall's bill has been held up in a Senate

committee since last fall. Without a good-Samaritan provision to protect them

from liability, they have few choices but to watch the Red and Bonita, and the

rest of their local mines, continue to drain.

— Michelle Nijhuis, The Atlantic (May 2010): Shafted

(Illustration by Mark Jeffries.)

But I think if you realize that the problem is built in, structurally, to electoral politics, the response doesn’t need to be despair. It can be motivation. Instead of sitting around watching their rivers die and waiting for Senator Mark Udall Of Colorado to pass a bill to legalize their direct action, what I’d suggest is that the local environmental groups in Colorado stop caring so much about what’s legal and what’s illegal, consider some countereconomic, direct action alternatives to governmental politics, and perform some Guerrilla Public Service.

I mean, look, if there are places where it would be simple enough just to go up there with a shovel and redirect the water,

then wait until nightfall, get yourself a shovel and go up there. Take a flashlight. And some bolt-cutters, if you need them. Cement plugs no doubt take more time, but you’d be surprised what a dedicated crew can accomplish in a few hours, or a few nights running. If you do it yourself, without identifying yourself and without asking for permission, the EPA doesn’t need to know about it and the Clean Water Act can’t do anything to punish you for your halfway

clean-up.

The Colorado rivers don’t need political parties, permits, or Public-Interest Groups. What they need is some good honest outlaws, and some Black-and-Green Market entrepreneurship.

See also:

They swarmed the front porch, hurled a flash-bang grenade through the plate-glass window into the living room, and then Officer Joe Weekley,

They swarmed the front porch, hurled a flash-bang grenade through the plate-glass window into the living room, and then Officer Joe Weekley,