El pueblo unido jamás será vencido!

It’s been a good two weeks since I meant to put up a post on some great labor news–the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ have won the Taco Bell boycott after four years of ground-breaking organizing and agitating for and by the migrant farmworkers of southern Florida in the Taco Bell Boycott and Boot the Bell!

campaigns. You can read more about it from the CIW themselves.

March 8, 2005 (IMMOKALEE/LOUISVILLE) – In a precedent-setting move, fast-food industry leader Taco Bell Corp., a division of Yum! Brands (NYSE: YUM), has agreed to work with the Florida-based farm worker organization, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), to address the wages and working conditions of farmworkers in the Florida tomato industry.

Taco Bell announced today that it will fund a penny per pound

pass-throughwith its suppliers of Florida tomatoes, and will undertake joint efforts with the CIW on several fronts to improve working conditions in Florida’s tomato fields. For its part, the CIW has agreed to end its three-year boycott of Taco Bell, saying that the agreementsets a new standard of social responsibility for the fast-food industry.…

Taco Bell has recently secured an agreement with several of its tomato-grower suppliers, who employ the farmworkers, to pass-through the company-funded equivalent of one-cent per pound directly to the workers.

With this agreement, we will be the first in our industry to directly help improve farmworkers’ wages,added Brolick,And we pledge to make this commitment real by buying only from Florida growers who pass this penny per pound payment entirely on to the farmworkers, and by working jointly with the CIW and our suppliers to monitor the pass-through for compliance. We hope others in the restaurant industry and supermarket retail trade will follow our leadership.Yum! Brands and Taco Bell will also work with the CIW to help ensure that Florida tomato pickers enjoy working terms and conditions similar to those that workers in other industries enjoy.…

The Company indicated that it believes other restaurant chains and supermarkets, along with the Florida Tomato Committee, should join in seeking legislative reform, because

human rights are universal and we hope others will follow our company’s lead.

The penny-per-pound increase means a cost increase of only $100,000 / year for Taco Bell. Here’s what it means for migrant farmworkers:

As part of the agreement announced Tuesday, Taco Bell will pay an extra penny paid per pound — about $100,000 annually — that will be funneled to about 1,000 farm workers through a small group of suppliers, Yum! spokesman Jonathan Blum said. Taco Bell buys about 10 million pounds of Florida tomatoes a year, Blum said.

Lucas [Benitez], co-director of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, said farm workers earn about $7,500 a year, without health insurance or paid vacations. The extra penny added per pound picked will almost double the yearly salaries of the roughly 1,000 farm workers employed by Taco Bell suppliers, [Benitez] said.

— Miami Herald 2005-03-09: Taco Bell agrees to pay extra pennies for tomatoes

Which the CIW is planning as we speak.

So, feel free to eat at Taco Bell again. In fact, I’ll be going out for dinner at Taco Bell tonight to thank them now that they have given in to farm workers’ demands, and I’ll be contacting them to be sure that they know why I’m buying food from them again.

This is a major victory for the CIW and for farmworkers as a whole. There’s a lot that organized labor can learn from it: how CIW won while overcoming barriers of language and nationality, assembling a remarkable coalition in solidarity (from students to fellow farmworkers to religious organizations and onward), drawing on the dispersed talents of agitators and activists in communities all across the country, and making some brilliant hard-nosed strategic decisions (e.g., the decision a couple of years ago to begin the Boot the Bell campaign–which hit Taco Bell where it hurts by denying it extremely lucrative contracts with college and University food services). I only know a bit of the story from following the boycott, and I already know that it’s a pretty remarkable story to tell. I look forward to hearing more.

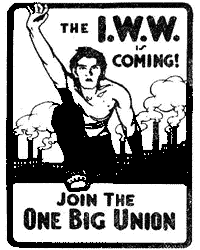

It’s also — although you won’t hear this as much — a major victory for government-free, syndicalist labor organizing. The CIW is not a bureaucratic government-recognized union; as a form of organizing it’s far closer to an autonomous workers’ syndicate or a local soviet (in the old sense of a democratic, community-based workers’ council, not in the sense of the hollow state apparatus that the Bolsheviks left after the party committees seized power at bayonet-point). Of course, not having the smothering comfort of the US labor bureaucracy to prop them up has often made things harder on the CIW; but it’s also made them freer, and left them free of the restraints on serious and innovative labor activism that have held the government-authorized union movement back for the past 60 years. (Example: the strategic decision to target Taco Bell in the first place–that is, the whole damned campaign that allowed the Immokalee workers to win such a huge improvement in their standard of living–was a secondary boycott

, and so would have been illegal under the terms of the Taft-Hartley Act and the Landrum-Griffin Act. But since the CIW doesn’t need a permission slip from the NLRB to engage in direct action, they won the day–not in spite of, but because of their freedom from government restraints on labor organizing.

Unfortunately, some of my libertarian comrades haven’t been quite so willing to celebrate. In fact, I first heard about the victory from Daniel D’Amico’s post lamenting the development. D’Amico wrote a misguided attack on the campaign before and so did Art Carden. The problem is that the arguments given in these articles seem to proceed from a double confusion: first, a confusion about the nature of CIW; and second, a confusion about economics and the nature of market processes.

Both Carden and D’Amico seem to make the initial mistake of thinking about the CIW campaign entirely by analogy to either (a) the student anti-sweatshop movement or (b) government-authorized trade unionism, and so feel free to lift boilerplate from the standard arguments against those (e.g.: that it is the misguided effort of patronizing college students who ought to pay more attention to the real interests of those they claim to act on behalf of; that it courts the coercive power of the State in order to achieve its goals) when it is in fact completely alien to how CIW actually works. They’ve never requested government assistance against Taco Bell, and they couldn’t legally get it if they asked. And whether the standard accusations against student-driven anti-sweatshop organizing are apt or inapt (I think they are apt in some aspects and unfair in others), they don’t apply to CIW. It’s certainly true that they’ve been more than willing to draw support from anti-sweatshop organizations and to draw comparisons between their struggle and the anti-sweatshop movement in order to curry support on college campuses (and did so very intelligently); but this isn’t the anti-sweatshop movement. It’s not directed from college campuses; the shots are called by a community organization of immigrant farmworkers in Southern Florida. You might try to argue that they’re acting foolishly against their own interests, or avariciously at the expense of other people’s legitimate interests, but to simply try to lift the standard Where are all the third world workers in the anti-sweatshop movement?

objections won’t hold water for anyone who has actually met (as I have) CIW organizers.

Carden and D’Amico’s articles are both mostly about their economic complaints against the CIW strategy; they may think that they can simply dismiss any mistakes about how CIW organizes as marginal to the main point. That’s fine, but the economic complaints are also unfounded. D’Amico, for example, complains that CIW is interfering with the market processes that set wages for labor:

CIW expects the boycott to put pressure on Taco Bell to pay more for its tomatoes and thus more for migrant laborers. But this would not be a sustainable market scenario. Prices are not set by arbitrary moral standards, but rather by available levels of supply and demand in the market.

…

Stopping the market transactions of mutually benefiting exchange in the name of moral obligations does not produce anything of lasting value to assist in capital accumulation or increasing standards of living.

But the entire complaint presupposes two things which are in fact false: first, that the moral demands on Taco Bell to improve its contracting for tomato-picking so that farmworkers are paid a better wage are arbitrary; second, that moral obligations are not part of what people take into account when they determine which transactions count as mutually beneficial

in the first place. Let’s bracket the first presupposition for a moment in order to clear away the second: prices and markets are not mechanistic systems; they are the results (both intended and unintended) of people’s choices. Notice how little attention this point gets when D’Amico offers the following weirdly primitive picture of how someone decides whether or not to buy a taco:

The value of a chalupa is not imputed through the sweat equity of the Immokalee migrant workers. When the typical college kid is watching his favorite episode of The Simpson’s and a Taco Bell commercial comes on, he does not pause and reflect on the condition of the plighted migrant laborer; rather he sees a funny Chihuahua that speaks Spanish, standing next to a greasy bundle of cheesy goodness, and his stomach growls accordingly.

Of course, I’m sure that some people do think like this about their meals, but there is no reason that they have to. When you are trying to figure out how people will make the choices they make, you always need to refer to a notion of benefit

. But the judgments of benefit that people make don’t just issue from some hydraulic system of inborn drives and aversions; they are the result of deliberation, and involve answers to a lot of questions about not only hunger, thirst, low-grade humor, etc., but also decisions about what kinds of pleasures are worth the cost, what sort of life you want to live, what sort of society you want to live in, and so on. Sure, not everyone thinks about those things when they deliberate over whether to go to Taco Bell or not; and the fact that they don’t ponder them had heretofore meant that wages would be as low as they were. But what the hell were CIW doing if not trying to educate people about the conditions that people picking the tomatoes they eat face, and so encouraging them to think about whether a marginal decrease of less than a penny per chalupa is really worth it to them? That’s as much a part of the free market as deliberations which issue in decisions to seek the lowest price at any cost are.

What about the first issue? Is it right to think that workers deserve more than they get paid, or is it foolish? D’Amico might try to push his point here by arguing: sure, given that you can convince people of those values, that’s as much a part of market processes as anything. But it shouldn’t be a part of people’s values; it’s foolish and economically destructive to act on the preference that people deserve extra money just for being hard workers that you feel sorry for, and not for any marginal increase in the valuable material output that they produce. So the campaign has gotten people to agree to giving the farm workers more than they should get if our aim is greater economic prosperity and higher standards of living. Which it should be.

But again, this seems to presuppose a weirdly mechanistic picture of the economic concepts involved. Prosperity

and higher standard of living

are irreducibly evaluative terms no less than mutually beneficial

; and you have to ask whether it’s possible to exclude basic considerations of fairness and solidarity with our fellow workers from a reasonable conception of what counts as a prosperous commonwealth and what doesn’t. Furthermore, even if you grant D’Amico his principle, it’s unclear why he’s as certain as he is that it applies here. He points to the backward imputation of value and seems to be taking for granted the standard economic argument that at equilibrium, wages are set by the worker’s marginal productivity. Since workers were making sub-poverty wages from the tomatoes for tacos before sentimental comparisons of their yearly income to the average came into play, it must be that those sub-poverty wages reflect their marginal productivity to the consumers of tacos when consumers of tacos are thinking only about the factors that D’Amico thinks they ought to think about.

But that conclusion rests on at least two unargued premises: (1) that farmworkers’ wages are set in a free market for labor, and (2) that farmworkers’ wages are at the equilibrium point. But why should we believe either of these? As CIW itself has repeatedly demonstrated, farmers and caudillos in Southern Florida have repeatedly been willing to use violence, coercion, and fraud against their laborers, up to and including outright slavery; and since many of the workers in Immokalee and elsewhere are undocumented, they also have to face the constant threat of violence from La Migra. All of these factors use coercion to undermine farm workers’ wages and bargaining positions. Further, even if the market were completely free, that wouldn’t be any guarantee at all that it would be no guarantee that wages would be set at marginal productivity given how consumers evaluate the taco; that argument depends on the kind of neo-classical anti-economic argument that I think Roderick Long rightly criticized as the doctrine of Platonic Productivity.

All of this is too damn bad. Not just because it makes for mistaken conclusions, but also because the willingness to make those mistakes tends to paint 21st century libertarians as court intellectuals for the bosses of the world, and it puts them directly at odds with their 19th century forebearers. Radical individualists like Benjamin Tucker, for example, defined their position as both the most consistent form of free market economics, and the most consistent form of the labor movement. Sure, part of that position was based on economic and philosophical error–e.g., commitment to the Smithian labor theory of value–but part of what I hope to show in all this is that corrections to their economic premises don’t require abandonment of their economic conclusions. In fact, if you want to learn something about how people can get together and make their lives both freer and happier in the course of just a few years, without the false help and bureaucratic meddling of the State, you’d do well to look at what the CIW has accomplished over the past several years.

So here’s to libertarian labor organizing and state-free struggle. ¡Si se puede!