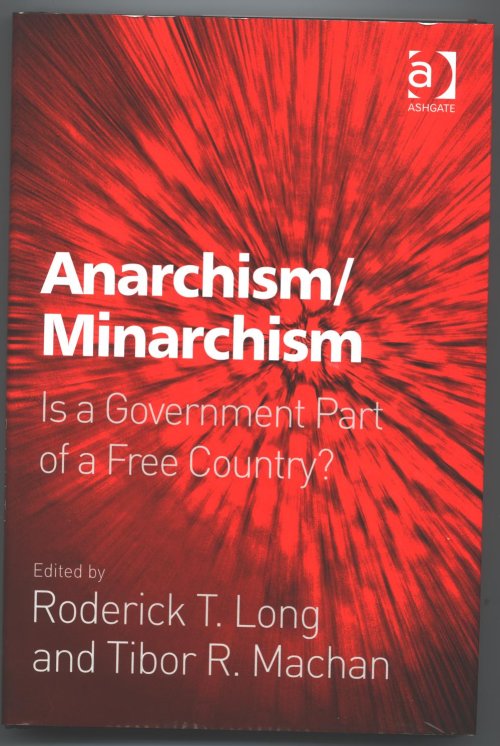

Here’s what I got in the mail Monday afternoon. It took a week longer to reach me than it did to reach Roderick; I don’t know whether that’s one of the perks of being an editor rather than a mere contributor like me, or simply because I’m way out west and he’s in Alabama.

Liberty, Equality, Solidarity: Toward a Dialectical Anarchism

The purpose of this essay is political revolution. And I don’t mean a revolution

in libertarian political theory, or a revolutionary new political strategy, or the kind of revolution

that consists in electing a cadre of new and better politicians to the existing seats of power. When I say a revolution,

I mean the real thing: I hope that this essay will contribute to the overthrow of the United States government, and indeed all governments everywhere in the world. You might think that the argument of an academic essay is a pretty slender reed to lean on; but then, every revolution has to start somewhere, and in any case what I have in mind may be somewhat different from what you imagine. For now, it will be enough to say that I intend to give you some reasons to become an individualist anarchist, and undermine some of the arguments for preferring minimalist government to anarchy. In the process, I will argue that the form of anarchism I defend is best understood from what Chris Sciabarra has described as a dialectical orientation in social theory, as part of a larger effort to understand and to challenge interlocking, mutually reinforcing systems of oppression, of which statism is an integral part—but only one part among others. Not only is libertarianism part of a radical politics of human liberation, it is in fact the natural companion of revolutionary Leftism and radical feminism.

My argument will take a whole theory of justice—libertarian rights theory—more or less for granted: that is, some version of the non-aggression principle

and the conception of negative

rights that it entails. Also that a particular method for moral inquiry—ethical individualism—is the correct method, and that common claims of collective obligations or collective entitlements are therefore unfounded. Although I will discuss some of the intuitive grounds for these views, I don’t intend to give a comprehensive justification for them, and those who object to the views may just as easily to object to the grounds I offer for them. If you have a fundamentally different conception of rights, or of ethical relations, this essay will probably not convince you to become an anarchist. On the other hand, it may help explain how principled commitment to a libertarian theory of rights—including a robust defense of private property rights—is compatible with struggles for equality, mutual aid, and social justice. It may also help show that libertarian individualism does not depend on an atomized picture of human social life, does not require indifference to oppression or exploitation other than government coercion, and invites neither nostalgia for big business nor conservatism towards social change. Thus, while my argument may not directly convince those who are not already libertarians of some sort, it may help to remove some of the obstacles that stop well-meaning Leftists from accepting libertarian principles. In any case, it should show non-libertarians that they need another line of argument: libertarianism has no necessary connection with the vulgar political economy

or bourgeois liberalism

that their criticism targets.

The threefold structure of my argument draws from the three demands made by the original revolutionary Left in France: Liberty, Equality, and Solidarity. I will argue that, rightly understood, these demands are more intertwined than many contemporary libertarians realize: each contributes an essential element to a radical challenge to any form of coercive authority. Taken together, they undermine the legitimacy of any form of government authority, including the limited government

imagined by minarchists. Minarchism eventually requires abandoning your commitment to liberty; but the dilemma is obscured when minarchists fracture the revolutionary triad, and seek liberty

abstracted from equality and solidarity, the intertwined values that give the demand for freedom its life, its meaning, and its radicalism. Liberty, understood in light of equality and solidarity, is a revolutionary doctrine demanding anarchy, with no room for authoritarian mysticism and no excuse for arbitrary dominion, no matter how limited

or benign. . . .

— Liberty, Equality, Solidarity: Toward a Dialectical Anarchism in Roderick T. Long and Tibor Machan (eds.), Anarchism/Minarchism: Is a Government Part of a Free Country. Ashgate Press, ISBN 978-0-7546-6066-8. 155–157.

The good news, for those whose interest is piqued and who would like to read the whole thing, is that the book is now available for pre-ordering and will be shipped somewhere around the end of the month. The bad news is that it’s about $80.00 for the hardcover edition, which is, for the time being, the only edition there is. (If you’re interested in reading the essay but are unlikely to have the bread to buy the book anytime soon, contact me privately.) In any case, for those who do get a chance to read the essay, I’d be glad to hear what you think, or any questions you may have, in the comments section at this post.

I mention this in the essay, but I’d like to repeat it here while I have the chance: the debts I accumulated in the process of writing this essay, and the earlier work on which it drew, are too numerous to give an accounting of them all, but I would especially like to thank my companion Laura and my teacher Roderick. The essay would have been much the poorer, or simply nonexistent, without their patience, inspiration, collaboration, encouragement, and detailed and very helpful comments