Translation of Message from CDH-UCAB: on torture and cruel and inhuman treatment of the detainees from 12-F (Centro de DDHH de la UCAB, reprinted in EL LIBERTARIO)

Here is another report on the protests and government repression Venezuela, originally published by the Center for Human Rights at UCAB, and re-posted online by the Venezuelan anarchist paper EL LIBERT@RIO. Inline links and editorial notes in footnotes are added by me. The same caveats apply as elsewhere; if you notice any mistakes or mangling please feel free to point them out in the comments, and I’ll attach a note or a correction to the text here.

Message from CDH-UCAB: On Torture and Cruel and Inhuman Treatment of the Detainees from 12-F.

Human Rights Center at UCAB

In a press notice published by the newspaper ?@c3;161;ltimas Noticias and reproduced with additional and equally false reports by the Sistema Bolivariano de Informaci?@c3;b3;n y Comunicaci?@c3;b3;n (SIBCI),[1] reference is made to a supposed declaration by the Center for Human Rights at UCAB[2] (CDHUCAB) in order to downplay the importance of the serious accusations by spokespeople of Foro Penal about the torture of people detained in Valencia, in the state of Carabobo.[3]

It’s necessary to clarify concerning:

The CDH-UCAB had no direct contact with those detained in Valencia, Carabobo, so it can neither confirm nor deny these allegations which, because of their severity, require an investigation by the authorities, independently, without intimidation or retaliation against the victims or the accusers, without anyone being disqualified ahead of time,[4] and following international standards that bind Venezuela as a country party to the International Convention against Torture.

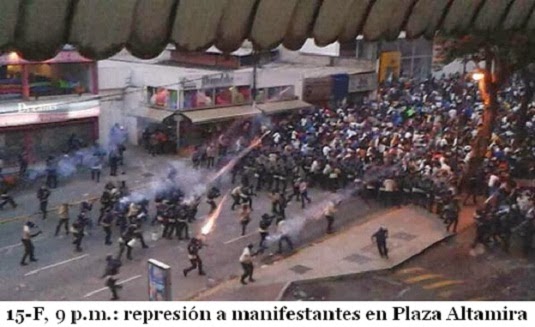

Beginning February 12, teams of lawyers from CDH-UCAB have given support to detainees in the capital region, having responded, from the early hours of the 13th, to invitations from many communications media, in which, because they were still in the process of locating detainees, were unable to supply detailed information about the conditions of detention they faced, without having meant, as we stated in many media outlets, that there was or was not torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.

The CDH-UCAB did warn, within a few hours of the first detentions, that it was worried about the detainee’s lack of access to their families and lawyers, since under that condition the conditions of detention could not be verified, to which was added the seizure of their cellular phones, preventing any communication.

After visiting various detention centers and having had contact with a considerable number of detainees and their families, the CDH-UCAB has identified a series of unacceptable situations that affect many different rights, including the penalization of protest, the minimum guarantees to the detained, the guarantees of due process and the conditions of detention, among which there have been acts which could qualify as torture or cruel and inhuman or degrading treatment, in accord with the UN Convention against Torture:

a. In practically every case with a verdict, the judges have included an injunction prohibiting those convicted from demonstrations, a sanction that the law does not expressly provide for, and which violates the constitutionally-protected right to peacefully demonstrate.

b. In nearly the totality of the cases, the families have been arbitrarily denied from seeing the detainees. This has basically happened in the detention centers of CICPC[5] and those of the National Guard. In all cases in which they banned families from seeing their detained relatives, the authorities have alleged “orders from higher up.”

c. The conditions of the places that they have used as centers of detention are in some cases absolutely inadequate, this is the case of the National Guard Command located in La Dolorita, in which 18 youths — the majority students — were held for 2 days in the same extremely small room, without a functioning bathroom, without adequate ventilation, without beds or mats, and without These conditions were noted directly by lawyers from CDHUCAB, who also verified the presence of a functionary from the Public Defender’s,[6] who, in spite of these inhuman conditions, had not issued reports on it.

d. In some cases the families were not even permitted to make telephone contact with the detained for 48 hours or more during the time they were detained, which is not only a violation of the most basic rights of detainees and families, but has even generated some accusations of

disappearingprisoners[7] that ceased after some hours, and which could have been avoided with relevant information about the whereabouts of the detainees, as established by international standards.e. Many detainees were not brought before a judge, or in the process of being brought before a judge, within the 48 hour limit that the law refers to. Some had spent 56 to 60 hours without being presented to a court, as was the case of Hugo[8] Gerrero, a professor at UCV,[9] who the judge finally freed with apologies, because he was not even participating in the protest.

f. In the great majority of the cases the lawyers have not been able to have private conversations with the detainees. When they have permitted a lawyer access to see their defendants in the detention centers, at least one official has always been present during the entire conversation, limiting the possibility for the detainees to clearly report the actions and the treatment that they are receiving in detention.

g. Practically all the detained have made accusations that they have been assaulted psychologically and many physically. The psychological attacks range from threats of being physically assaulted or even threats that they would be raped. The physical attacks range from minor injuries on different parts of the body, up to highly sensitive situations we are in the process of verifying.

h. In some cases an undue delay is produced in order for the detainees to be brought to the show-cause hearing. That is to say, to the time of detention (which many times exceeds the legal maximum time of 48 hours) in some cases up to 10 or 12 more hours are added to be heard by the judge in the show-cause hearing.

i. Without a judge’s order, in the majority of the cases security forces reviewed the private information contained in detainees’ cellular phones or electronic devices (their e-mails, text messages, photos, etc.), and, on occasions, have proceeded to offload images that could document excesses by the security forces of the State.

In addition to some deeds which the CDH-UCAB is still investigating, the situations we just described are also contrary to the Convention against Torture, to which Venezuela is a party, and contravene the standards to apply to all detainees under this and under the Special Law to prevent and punish torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment,[10] whenever the obstacles presented by those responsible for the custody of the detainees are contrary to the procedures required for the prevention of torture, involving those officials in responsibility for acts that can be investigated and punished and which constitute human rights offenses with no statute of limitations.[11]

Finally, the CDH-UCAB rejects this new attempt by SIBCI to discredit the work of Provea,[12] alleging a supposed source of funding

noted for financing groups against government in the countrywhile remaining silent, just like the Public Defender’s office,[13] about the kidnapping and assault of the same organization’s Media Coordinator,[14] acts which, it is worth noting, also form part of the conduct which the State is obligated to investigated and punished due to the commitments assumed by the UN Convention against Torture. This accusation has been lodged at the office of the Attorney General and the Public Defender’s.[15]Caracas, 18 February 2014

–Translation of Comunicado del CDH-UCAB: Sobre torturas y trato cruel e inhumano de detenidos del 12F. Translated by Charles W. Johnson

- [1]A propaganda system established and operated by the Venezuelan government.↩

- [2]Centro de Derechos Humanos, at the Universidad Cat?@c3;b3;lica Andrés Bello, a private university, which is one of the largest universities in Venezuela.↩

- [3]See for example Foro Penal: Hay torturas (

Foro Penal: There is torture

), 22 Feb. 2014.↩ - [4]Lit. “apriori disqualifications.”↩

- [5]Cuerpo de Invasticaiones Cientificas, Científicas, Penales y Criminalísticas, Venezuela’s largest national police force and forensic investigation agency.↩

- [6]Lit. Defensoría del Pueblo, an ombudsman’s office which is tasked with monitoring, promoting and defending human rights under the Venezuelan constitution. The office-holder is appointed for a 7-year term by a committee on the national legislature.↩

- [7]Lit.

denuncias de desapariciones fisicas,

a reference to the long-standing dirty-war tactic ofdisappearing

enemies of the regime, i.e. imprisoning and murdering them in secret, while officially denying knowledge of their condition or their whereabouts.↩ - [8]

Hug

in text; this seems to be a typo.↩ - [9]Universidad Central de Venezuela, a public university in Caracas.↩

- [10]

Ley Especial para prevenir y sancionar la tortura y otros tratos crueles, inhumanos o degradantes,

a Venezuelan national law.↩ - [11]Lit.

delitos imprescriptibles,

imprescriptible or inextinguishable offenses, a category in international law applying to, for example, torture, disappearance, war crimes and crimes against humanity.↩ - [12]Programa Venezolano de Educaci?@c3;b3;n-Acci?@c3;b3;n en Derechos Humanos, a prominent Venezuelan human-rights NGO which has repeatedly criticized the Bolivarian government↩

- [13]Again, Defensoría del Pueblo, the government’s human-rights ombudsman.↩

- [14]Inti Rodríguez, the media coordinator of Provea, was allegedly kidnapped on February 12 by about 20 disguised men who interrogated, beat, and threatened to kill him, which he claims to have included pro-government paramilitaries and (from the language they used in the interrogation) possibly also members of police or intelligence agencies.↩

- [15]Again, Defensoría del Pueblo, the government’s human-rights ombudsman.↩