Posts tagged World War I

Two Sonnets for Memorial Day

(To Jessie Pope,[1] etc.)

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge

Till on the haunting fires we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of disappointed shells that dropped behind.

GAS! Gas! Quick, boys! An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And floundering like a man in fire or in lime.—

Dim, through misty panes and thick green light

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest,

To children ardent for some distant glory

The old lie: DULCE ET DECORUM EST

PRO PATRIA MORI.[2]–Wilfred Owen (Oct. 1917).

The poet, Wilfred Owen began work on this poem in October 1917 while on leave in England. This is his best known poem. He never completed it for publication, because a year later he was dead. On November 4, 1918 he was killed on the front in a meaningless battle for the Sambre–Oise Canal seven days before the warring governments finalized the Armistice.

- [1]Jesse Pope was an Leicester poet who wrote light verse before the Great War and then during the War published a series of patriotic poems in the Daily Mail urging young men to enlist and celebrating patriotic sacrifice, using verse like the following:

Who’s for the Game, the biggest that’s played / The red crashing game of a fight? Who’ll grip and tackle the job unafraid / And who thinks he’d rather sit tight? . . . / Who knows it won’t be a picnic–not much– / Yet eagerly shoulders a gun? / Who would much rather come back with a crutch / Than lie low and be out of the fun?

↩ - [2]A line from the imperial poet Horace’s Odes. In English,

Sweet it is and becoming to die patriotically [= for the patria].

In 1913, shortly before the outbreak of the War, the line was carved into a wall at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.↩

War is not a weapon you can aim

. . . In June, I deployed several hundred American servicemembers to Iraq to assess how we can best support Iraqi security forces. Now that those teams have completed their work — and Iraq has formed a government — we will send an additional 475 servicemembers to Iraq. As I have said before, these American forces will not have a combat mission — we will not get dragged into another ground war in Iraq. But they are needed to support Iraqi and Kurdish forces with training, intelligence and equipment. We’ll also support Iraq’s efforts to stand up National Guard Units to help Sunni communities secure their own freedom from ISIL’s control.

—Barack Obama, Remarks on ISIL/ISIS and war on Syria and Iraq, 10 September 2014

This is a promise that is foolish to make. Maybe he’s right that the proxy wars on the ground and the U.S. war in the air won’t end up dragging U.S. forces deeper into a quagmire on the ground. But there is no way he can confidently promise this. War is not a weapon that you can aim, not even if you are President of the United States, and expect that you’ll hit exactly what you hoped to, with no complications or unexpected results. Modern wars are always conducted on the basis of classified information, secret strategic interests that are not disclosed to the public, half-accurate information and politically-filtered intelligence. They operate away from any possibility of informed consent by ordinary people, who don’t have access to the information government keeps secret, and indeed even away from the possibility of informed decisions by that government, which finds itself blundering through the fog of its own secrecy, errors, self-deception and political rationales. Wars develop a logic of their own and they always involve both deception of the public about the likely outcomes, and also consequences unintended or unforeseen even by their architects. It wouldn’t be the first time that U.S. military advisors

got drawn into a land war in Asia. It wouldn’t even be the first time that U.S. build-up was really only a prelude to a wider war in Iraq.

Certainly, it has already proven a prelude to bringing the U.S. war power into a wider regional war.

The pacifist is roundly scolded for refusing to face the facts, and for retiring into his own world of sentimental desire. But is the realist, who refuses to challenge or to criticise facts, entitled to any more credit than that which comes from following the line of least resistance? The realist thinks he at least can control events by linking himself to the forces that are moving. Perhaps he can. But if it is a question of controlling war, it is difficult to see how the child on the back of a mad elephant is to be any more effective in stopping the beast than is the child who tries to stop him from the ground.

The ex-humanitarian, turned realist, sneers at the snobbish neutrality, colossal conceit, crooked thinking, dazed sensibilities, of those who are still unable to find any balm of consolation for this war. We manufacture consolations here in America while there are probably not a dozen men fighting in Europe who did not long ago give up every reason for their being there except that nobody knew how to get them away.

–Randolph Bourne, War and the Intellectuals ¶ 12

Seven Arts (June, 1917).

End all war, immediately, completely, and forever.

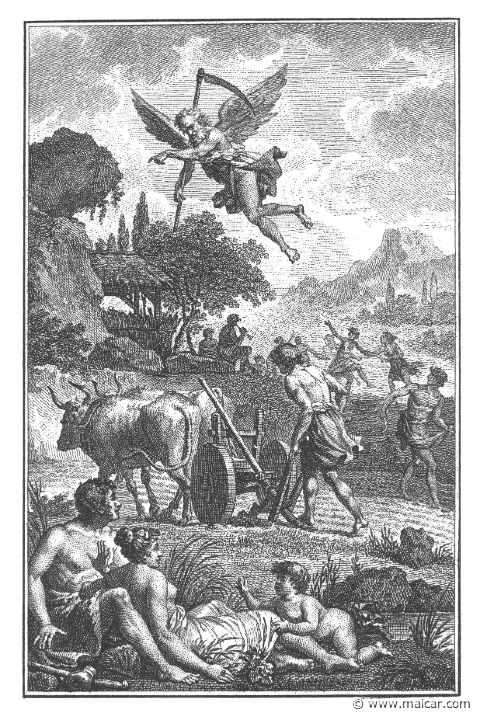

The Age of Bronze

As we approach the New Year, we naturally think of ends, and of beginnings; what has changed, and what we have lost. So hey, libertarians, let’s all get together and feel sorry about the golden age of Limited Government and Individual Liberty we have lost. Remember the ancient liberties that we all enjoyed only 60 years ago, back in the 1950s? Back when all military-age men were subject to the draft, people were being interrogated before a permanent committee of Congress over their political beliefs, the FBI was conducting massive illegal wiretapping, surveillance and disruption against nonviolent civil rights activists, the National Security Agency was established as a completely secret surveillance arm of the federal government, it was illegal for married or unmarried women to buy basic birth control, it was made illegal for anyone to buy any scheduled drug without a doctor’s prescription, government was conducting medical experiments on unwilling human subjects[1], Urban Renewal was demolishing the core of every major U.S. city to build government highways and housing projects, and massive community-wide immigration raids were terrorizing undocumented migrants throughout the Southwest.

Or like back in the 1940s when government spending was over 50% of GDP, nearly the entire consumer economy was subject to government rationing, Japanese-Americans were forced into internment camps, and a secret government conspiracy was building an entire network of secret cities in order to build atomic bombs to drop on civilian centers.

Or like back in the 1930s when the entire institutional groundwork of the New Deal was being implemented, Roosevelt was making himself president-for-life, government attempted to seize all gold or silver bullion in private hands, the federal government first instituted the Drug War, Jim Crow was the law of the land, Congress created the INS, Jews fleeing the incipient Holocaust in Europe were being turned away by immigration authorities, and psychiatrists were using massive electric shocks or literally mutilating the brains of women and men confined to asylums.

Or like the 1920s when it was illegal to buy alcoholic drinks anywhere in the United States, tariff rates were nearly 40% on dutiable imports, Sacco and Vanzetti were murdered by the state of Massachusetts, the Invisible Empire

Second Era Klan effectively took over the state governments of Colorado, Indiana, and Alabama, hundreds of black victims were massacred in race riots in Tulsa and Rosewood, when Congress created the Federal Radio Commission[2], the US Border Patrol, passed the Emergency [sic] Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924, and the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the authority of the state to forcibly sterilize women deemed “feeble-minded” or “promiscuous” for eugenic purposes.

Or the 1910s, when the federal government seized control of foreign-owned companies to facilitate production of chemical weapons, imposed the first-ever use of federal conscription to fight an overseas war, invaded Haiti, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Mexico[3], Russia, and Europe, passed criminal anarchy and criminal syndicalism statutes, tried and convicted hundreds of people for belonging to radical unions, imprisoned hundreds of people for protesting the draft during World War I (ordered by the President of the United States and upheld by the Supreme Court in one of its most radical anti-free-speech decisions), deported hundreds of people solely for holding anti-state political beliefs, the Mann Act made it illegal to “transport women across statelines for immoral purposes” [sic], the Colorado National Guard machine-gunned and burned alive striking miners and their families in order to break a UMWA organizing campaign, and Congress created the Federal Reserve, the Income Tax, the Espionage Act, and the Sedition Act.

Or maybe like the 1900s. . . . .

- [1]See also the biological and radiological experiments documented here, and the Guatemala syphilis experiment conducted from 1946-1948.↩

- [2]Created in 1926; later converted into the Federal Communications Commission in 1934.↩

- [3]In 1914, and then again in 1916-1917↩

War Realism

Here’s a passage from Randolph Bourne’s The War and the Intellectuals, which I’ve been re-reading lately. The essay was written for Seven Arts in 1917. The War that Bourne is discussing is World War I — a war now almost universally acknowledged to have been a disaster on all sides, nearly incomprehensible in its pointlessness, and hideous and utterly empty waste of human life. The intellectual class that he’s referring to is, above all, his former colleagues at The New Republic and other journals — men like John Dewey, Walter Lippman, and Herbert Croly, who considered themselves above all humanitarians, Progressives, and philosophical pragmatists.

A few keep up a critical pose after war is begun, but since they usually advise action which is in one-to-one correspondence with what the mass is already doing, their criticism is little more than a rationalization of the common emotional drive.

The results of war on the intellectual class are already apparent. Their thought becomes little more than a description and justification of what is already going on. They turn upon any rash one who continues idly to speculate. Once the war is on, the conviction spreads that individual thought is helpless, that the only way one can count is as a cog in the great wheel. There is no good holding back. We are told to dry our unnoticed and ineffective tears and plunge into the great work. Not only is everyone forced into line, but the new certitude becomes idealized. It is a noble realism which opposes itself to futile obstruction and the cowardly refusal to face facts. This realistic boast is so loud and sonorous that one wonders whether realism is always a stern and intelligent grappling with realities. May it not be sometimes a mere surrender to the actual, an abdication of the ideal through a sheer fatigue from intellectual suspense? The pacifist is roundly scolded for refusing to face the facts, and for retiring into his own world of sentimental desire. But is the realist, who refuses to challenge or to criticise facts, entitled to any more credit than that which comes from following the line of least resistance? The realist thinks he at least can control events by linking himself to the forces that are moving. Perhaps he can. But if it is a question of controlling war, it is difficult to see how the child on the back of a mad elephant is to be any more effective in stopping the beast than is the child who tries to stop him from the ground. The ex-humanitarian, turned realist, sneers at the snobbish neutrality, colossal conceit, crooked thinking, dazed sensibilities, of those who are still unable to find any balm of consolation for this war. We manufacture consolations here in America while there are probably not a dozen men fighting in Europe who did not long ago give up every reason for their being there except that nobody knew how to get them away.

— Randolph Bourne, The War and the Intellectuals (1917), ¶Â¶ 11-12.