Just shut the fuck up

Here's a pretty old post from the blog archives of Geekery Today; it was written about 17 years ago, in 2008, on the World Wide Web.

I don’t mean to be rude. But this issue is important.

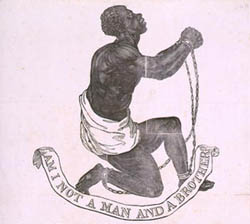

There are lots of reasons to despise Alexander Hamilton — given his record as a Caesarian centralizer, rampaging war-luster, and the spiritual and political father of U.S. state capitalism. There are also lots of cases where Thomas Jefferson was better than Hamilton on things that Hamilton was rotten on. This should be taken into account if you are ever trying to rank U.S. revolutionaries according to their libertarian merits. But the reverse is also true, and the issues that Jefferson was rotten on — like, oh, slavery — were not small potatoes or minor personal foibles. And while I think that Will Wilkinson is making several interrelated mistakes, among them misrepresenting and unfairly minimizing the case against Hamilton, when he says…

If you think central banks are a bigger issue for liberty than human enslavement, trade, or the growth of capitalism then your priorities are screwed.

— Will Wilkinson (2008-04-07), comments on ABJ @ The Fly Bottle

… what I would like to stress, at the moment, is that if you ever, ever find yourself thinking that it might possibly be appropriate to reply to a remark like that by saying something like this:

Central banking is one of the worst forms of human enslavement, actually. You should try going out more often, WW, and read some Hoppe and DiLorenzo for good measure.

— Alberto Dietz (2008-04-09), comments on ABJ @ The Fly Bottle

Then you need to stop. Right there. And just–well, you know the rest.

Thomas Jefferson wrote a couple of documents that I admire very much. One of them I consider to be one of the finest and most important political documents written in the history of the world. But Jefferson was a man, not just the signature on a series of essays, and he also did many other things in his life. He was an overt and at times obsessive white supremacist. He was a rapist. He was a posturing hypocrite. He was President of the United States. He was himself a war-monger, who launched the United States’ first overseas war within months of his first inauguration. Most of all, he was a active slaver, a lifelong perpetrator of real, not metaphorical, chattel slavery. He violently held hundreds of his fellow human beings in captivity throughout their lives and throughout his, with the usual tools of chains and hounds and lashes. He maintained himself in an utterly idle life as a landed lord of the Virginia gentry by forcing his captives to work for his own profit, and living off of the immense wealth of things that they built and grew by the sweat of their own brows and the blood of their own backs. He had no conceivable right to live this life of man-stealing, imprisonment, robbery and torture, and no justification for it other than racist contempt for his victims and the absolute, violent power that he (with the aid of his fellow whites) held over the life and limb of hundreds of victims. He knew that his own words in the Declaration of Independence condemned his own actions towards his

slaves, who were by right his equals, beyond appeal, but he went on enslaving them anyway for the rest of his life and would not even make any provisions in his will to set them free when he finally died. He was a hereditary tyrant, claiming, based solely on his descent, the right to go on perpetrating a reign of terror over his prison-camp plantation more hideous and invasive than anything ever contemplated by the most absolutist Bourbon or Bonaparte. Not because he was in any way extraordinary or at all harsher than the average, compared to other white slavocrats, in how he treated his

slaves–but rather because that kind of terror and violence is part and parcel of what forcing hundreds of people into chattel slavery means. As insidious and destructive as government-centralized banking and the money monopoly may be — and I am the last person to deny that — it is callous, counter-historical, inhuman bullshit to try and pass it off as one of the worst forms of human enslavement

in comparison to American chattel slavery. It’s bullshit that needs to stop.

A side note. When trying to explain Jefferson’s view on slavery, one thing that a lot of people seem to take as a point in his favor is his opposition to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In 1807, Jefferson in fact signed a bill banning the trans-Atlantic slave trade (which could not take effect until 1808 because the U.S. Constitution only granted Congress the power to regulate the international slave trade 20 years after its ratification). It comes up a couple of different times in the same comments thread.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t actually speak in Jefferson’s favor. Jefferson, like many other white Virginian slave-camp commandants, was indeed for banning the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which he, like many other white Virginian slavers, sometimes fiercely denounced as infamous and inhumanly cruel. They were right about that part, and they were right that the trans-Atlantic slave trade ought to have been banned, but their primary reasons for wanting it banned were quite different from what people reading them today often conclude. If, after all, they were actually against the slave trade for humanitarian reasons, then they certainly ought to have the same problems with the internal slave trade in the United States, and the exportation of slaves out of the United States (for example, down to the death-plantations of the Caribbean). Those parts of the slave trade also involved the hellish passage of hundreds of slaves, shackled below decks, in sea voyages from New England or the upper South to the far-away places they were sold down to. But you’ll find little of that from Jefferson or his fellow white Virginian slavers, and the reason is that they profited from the internal slave trade. By the late 18th and early 19th century, Virginia was in the process of a long decline in agricultural productivity, but the landed lords held on to their stream of pirated wealth — by becoming the leading exporter of slaves to other, more productive plantations, down in the Deep South and in the Caribbean. Jefferson’s opposition to the slave trade, like that of many of his fellow Virginia slavers, was not nascent abolitionism. It was pure protectionism, designed to prop up the Virginian slave-traders’ profits while they retained the same absolute, violent power over their

slaves at home.

Hope this helps.

but but but… Jefferson has like 10^23 friends on myspace, he must be cool, right?

What would you say to the “argument” (well, I think it’s bullshit, hence the quotation marks) that Jefferson was a man of his time and therefore we ought not to judge him by our standards?

It’s ridiculous that, in a world of sex trafficking and multinational corporations enslaving people in developing countries, someone would call centralized banking one of the worst forms of slavery. That kind of rhetoric is why I would never call myself a libertarian.

“(T)he laws do not permit us to turn them loose” — Thomas Jefferson

Perhaps, had you done your homework, you would have noticed that Jefferson inherited his slaves, and that the laws of Virginia, both before and after the revolution, made it impossible for him to free them. You might also have noticed that the law which allowed George Washington to free his slaves upon his death (something Virginia’s laws prevented him from doing any sooner) was overturned by the time Thomas Jefferson died a quarter century later. But I guess bashing people about whom you apparently know almost nothing is a good way to spend your internet time.

While the rest of the site to which I’m about to link may be devoid of any intellectual merit, the article to which I’m linking is well sourced and well reasoned (so perhaps you should read it): http://www.wallbuilders.com/LIBissuesArticles.asp?id=99

By the way, in case you haven’t seen the first draft of the Declaration of Independence, you can find it in the Journals of the Continental Congress, Volume 5, pages 491 to 502. Page 498 is particularly interesting: http://memory.loc.gov/ll/lljc/005/0000/00830498.gif

SWABTR: Oh, there was a law?

I mean, we all know how famous Jefferson was for not agitating against unjust laws. A meek fellow, really.

You might consider rereading part of Rad Geek’s post again. Specifically, the “posturing hypocrite” part.

Serafina,

I think the argument involves several different layers of bullshit piled on top of one another.

On the factual level, it’s just not true that everyone of Jefferson’s time believed in slavery. In fact slavery was abolished throughout most of the northern states within Jefferson’s lifetime, based on a widespread conviction amongst Northern whites that it was incompatible with the libertarian and egalitarian principles behind the Revolution. (For eloquent expressions of the objections, see, for example Gouverneur Morris or Aaron Burr’s writings on slavery).

Jefferson was perfectly well aware of those moral objections, and he knew well that his own stated positions about justice and equality condemned slavery beyond appeal–as he repeatedly wrote–but he just didn’t give enough of a damn about it either to stop driving own slaves or even to publicly agitate against slavery in any way that mattered. But, besides the white people who voiced anti-slavery sentiment, of course, there were also millions of Southern black men, women, and children who were ardently opposed to being enslaved and who made no bones about showing it in words or deeds when they thought they might be able to do so without danger to life or limb. Any argument that tries to justify Jefferson’s position by reference to supposedly universal pro-slavery sentiment, but neglects to mention the sentiments of the hundreds of black slaves with whom Jefferson was in daily contact, just ends up re-inscribing white supremacy through a selective re-telling of history.

But there are other layers of bullshit involved. Particularly, the relativistic bullshit involved in acting as if black slavery were any less atrocious of a crime just because a bunch of white people all got together and decided amongst themselves that it was O.K. Even if it were true (as it is not) that contemporary sentiment was universally pro-slavery, that would be morally completely irrelevant; the issue here has to do with justice, not popularity. That same procedure could be used to excuse literally any atrocity in the history of the world, since, after all, any time other than the present was a different time, and generally the men who committed those atrocities had the support of a significant enough social movement in order for them to carry out large-scale violence. One may as well declare that we shouldn’t be so hard on Heinrich Himmler, because, after all, 60 years ago and, hey, Himmler was not that far out of step with the rest of the rising social trend of lethal fascist anti-Semitism. I think there is a really crude double-standard involved when people try to use distance in time in order to wash out blame, by claiming that being so far in the past somehow makes it less acceptable to treat people from the past as responsible human beings, but then turns around and tries to use those same moral standards, which were just dismissed as inapplicable, to claim that someone like Jefferson ought to be praised as a hero of liberty, justice, etc. If those words mean anything at all, then they most cut both ways–not only licensing praise where he acted to promote them, but also blame where he acted to violate them, and I can think of few violations as intense and obvious as chattel slavery.

For what it’s worth, I’ve responded to some similar arguments elsewhere, in the context of a discussion of Robert E. Lee.

As for rhetoric and labels, I agree with you that if all libertarians or even most of them went around saying that central banking is one of the worst forms of human enslavement, in the context of comparing it to real, non-metaphorical chattel slavery, then I would have little or no desire to call myself a libertarian. But I think, to be fair, that there are many self-identified libertarians who don’t go around spreading such obviously callous or counterhistorical nonsense. (While I disagree with Will Wilkinson about a lot of things, including a number of issues surrounding this specific topic, he is one example. Or, to take another libertarian whose views are somewhat closer to mine, J.R. Hummel has produced a lot of really excellent libertarian historical work that, among other things, takes slavery absolutely as seriously as the topic deserves, and aligns himself quite explicitly with the radical Garrisonian abolitionists. So long as there are enough honorable people using the term I’m not about to abandon it to slavery-denialist buffoons.

Someone,

— Thomas Jefferson

Three things.

First, as a matter of legal history, your representation of Virginia’s manumission laws is utterly bogus. Under Virginian colonial law, a slaveholder could manumit slaves by a special act of the legislature. This was often hard to get, but those who actually gave a damn took the trouble to get it; you can read several such special acts online. After the Revolution, at the behest of petitions from the Quakers and the Methodists, the Virginia state government passed a very liberal manumission law in 1782 (I mean liberal towards white slave-holders who wanted to manumit; freed blacks still suffered under a racial police state). From 1782 until 1806, any slaveholder in Virginia could manumit slaves for any reason, either in his will or while still living, In other words, Jefferson had 24 years in which he could have legally manumitted any or all of slaves by doing nothing more than drawing up the papers and getting them witnessed. He did nothing of the sort, because he didn’t give enough of a damn about the liberty of black people to give up the material comforts that he could get by continuing to live off of other people’s labor, and because he had convinced himself that, as he argued in Notes on the State of Virginia, ending slavery without exiling the freed blacks from their homes (and thus segregating the races) would be somehow catastrophic.

In 1806, after the Haitian Revolution and the exposure of Gabriel’s planned uprising, the Virginia legislature passed a new law which still provided for manumission at will, but imposed stricter requirements–most notably that freed blacks had to leave the state of Virginia within one year of being manumitted. Jefferson, as a segregationist and a colonizationist, approved of the scheme, but nevertheless he still didn’t manumit his slaves, even though the law still allowed for it. When Jefferson died in 1826 the law allowed for heirs to partially cancel manumission provisions in a will, under certain circumstances. But Jefferson never even tried, so there was nothing to cancel.

Meanwhile, even though Jefferson was for a long time a sitting legislator in the Virginia state legislature, he never proposed any statewide gradual emancipation law of any kind.

Looking strictly at the law, he had plenty of opportunities to legally free slaves over the course of decades, and he didn’t do a damned thing about it.

Second, whether or not the law allowed for formal manumission, there was nothing at all stopping Jefferson from treating slaves as equals — by letting them come and go as they pleased, by letting them work or not work as they pleased on what they pleased (and paying them a regular wage if he wanted them to work on some particular project they would not otherwise freely work on), and by dividing his own unearned land among them and treating them as fellow free farmers on those parcels. Even without securing formal manumission papers, nothing forced him to drive them into labor unwillingly or to steal the profits of their labor or to imprison them against their will, but Jefferson chose to do that anyway, because, again, he believed that black people were by and large not capable of governing their own lives and that he had a right to use violence in order to get what he wanted from them.

Third, as Robert Hutchinson rightly points out, even if you were right about the state of the law (as you are not), and even if we disregarded (as we should not) the fact that Jefferson was perfectly capable of end-running the law by respecting the rights and freedoms of black people on plantation even though they were legally designated as slaves, still, that would be no argument for letting Jefferson off the hook, morally speaking. The notion that Thomas Jefferson — sometime state legislator, sometime President of the United States, one of the most powerful and influential men in the new country, author of the Declaration of Independence, and veteran revolutionary — should sit around quaking about the possibility of evading or defying such a monstrously unjust and tyrannical law, hovers between obscenity and farce. If he really was in that position, then he should be condemned an unspeakable moral coward. If he was not, but rather followed the law because, in spite of his high-and-mighty rhetoric against the injustices of slavery, he preferred things to stay basically as they were, then he should be condemned as, again, a posturing hypocrite.

Yr motives are as pure as the driven slush in writing all that without once mentioning George Mason. The author of the Virginia preamble would not sign on to the slavers charter that was the US constitution.

Even as Jefferson stole his best lines.

Any fool knows that so what are you?

I’m sorry – I asked.

Jefferson did free some of his slaves. He wasn’t legally the full owner of them due to his debts, though he could have tried to get his finances in order to free more of them. Also, he took action against the internal slave trade. He proposed a law in 1784 that would have prohibited slavery in all the western territories (which would have included Alabama and Mississippi). It was defeated, as was his proposal in a 1783 draft of the Virginia constitution for the gradual emancipation of slaves. He was a racist, but probably less so than most at the time. He noted that because blacks had been oppressed he could not know what their true capabilities would be under freedom. He could still be a very bad person without being quite as you have depicted.

In modern-day state capitalism, if an employer uses his economic power over an employee to get her to have sex with him, would you also consider that rape?

TGGP,

In modern-day state capitalism, can a boss shackle and chain an employee, flay her with a whip, rob her of her children or parents, or sell her down to certain death in a Caribbean sugar plantation?

In case there was any confusion, I am not an anarchist or of the left and consider myself a supporter of capitalism. I do not the consider the modern occurrence of bosses inducing their employees to have sex with them to be analogous to the historical rape of chattel slaves but I was interested in the perspective of a left-libertarian anarchist.

As for rhetoric and labels, I agree with you that if all libertarians or even most of them went around saying that central banking is one of the worst forms of human enslavement, in the context of comparing it to real, non-metaphorical chattel slavery, then I would have little or no desire to call myself a libertarian.

Major Premise. Minor premise. Conclusion.

This is sadly a precise description of the most common psychology within libertarianism.

“In modern-day state capitalism, if an employer uses his economic power over an employee to get her to have sex with him, would you also consider that rape?”

Certainly, and that is an absolutely horrible situation. However, the sheer scale of that kind of oppression is not quite as horrific as American & Caribbean slavery, even though it remains the case that both are very horrific and a just society will tolerate neither. Casually comparing the two in the course of an argument does justice to neither.

TGGP,

O.K. Well, my own view is that what you’re describing is not rape in the strict sense (i.e., forced sex or sex where consent is impossible), but is absolutely vile conduct by the boss and violating for the sexually exploited worker. (If you want to slap on labels, it’s what would usually be called quid pro quo sexual harassment.) Also that personal mindset and prevailing male-supremacist rape culture involved in sexual harassment are more or less indistinguishable from the personal mindset and prevailing male-supremacist rape culture involved in sexual assault.

But if a woman told me about an experience like that and said she felt raped, I wouldn’t be confused as to her meaning, and I don’t think it would be necessary, desirable, or appropriate to her with a

The situation of a slaver having sex with a woman over whom he effectively has the power of life and death is closer in kind to, say, prison guards who sexually exploit prisoners under their lock and key–which I also consider to be rape in all cases, in virtue of the power, and thus background threat of violence, that the guards hold over the prisoners.

Here’s the problem (this applies to the critique of Lee as well): humans typically don’t like to juggle ambiguities and grey areas, so they prefer to put people in the “good” category or the “bad” category. Especially if it’s a historically relevant person, and especially if a lot of that history is still raw. Once a character is in one of these black and white categories, any hint that there might be some grayness is sacrilege. The “he was a man of his time” argument is just a way of saying that the character did things to put him in the “bad” category, but that the person doesn’t want to take him out of the “good” category.

The solution, of course, is to blame the categorical analysis for the confusion, not the person critiquing the analysis. This, however, would require people to return to their analysis – and why should they? We’ve been taught that history is just the study of facts, and that any opinions about history break down into “correct” and “incorrect”. That’s how you get your mind right for the highly regimented culture we occupy – accept the prefabbed opinions handed down.

As I think you’ve said before, RG, this whole issue of judging historical figures from the past says far more about us than it does about them.