Ihre Papiere, bitte

Here's a pretty old post from the blog archives of Geekery Today; it was written about 17 years ago, in 2008, on the World Wide Web.

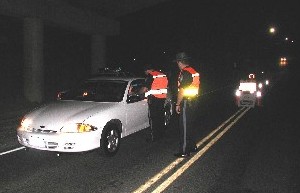

In its 2000 decision in Indianapolis v. Edmond, the US Supreme Court held that the city’s effort to attack the drug trade by holding a checkpoint to look for drugs was an unconstitutional violation of the Fourth Amendment’s protection of the right to be free from unwarranted searches and seizures. But in the years since then, a handful of departments across the county, usually in the South, have brazenly trumpeted their resort to drug checkpoints.

The latest department to step into the breach was Louisiana’s Beauregard Parish Sheriff’s Office, which held such a checkpoint last Thursday night near the town of Starks. Following the lead of sheriff’s deputies, the local newspaper was all over the story.

Narcotics checkpoint a success,blared the headline in Monday’s Derrider Daily News story on the police action. The article went on to explain how, following complaints of drug dealing in the neighborhood, police decided to take action:

The Beauregard Parish Sheriff’s Office set up a Narcotics Checkpoint Thursday night near Starks, Louisiana,the local paper reported.Due to several complaints coming from the Fields area, the BPSO put together a joint operation with the help of Sheriff Ricky Moses and the DeRidder city police department. The operations utilized several BPSO deputies as well as the new Drug Interdiction team led by Detectives Dale Sharp and Greg Hill. Seven police units total were used for the operation in addition to four other units performing regular patrols.The checkpoint resulted in three arrests for marijuana and hydrocodone possession, a quarter pound of marijuana being tossed from an unknown vehicle’s window, and a number of traffic citations.

If this really was a drug checkpoint, it is clearly unconstitutional,said Steve Silverman, executive director of the constitutional rights defense group Flex Your Rights.

Well, O.K., whatever. If you are ever hauled into court as the result of one of these checkpoints, that’s important information to have. But the problem is that cops are, as a rule, better at manipulating the court than you are; they are trained in how to exploit loopholes, how to manipulate people, and how to get cheap sympathy from judges and juries. As Silverman himself says:

If people went to court and fought it, the evidence would be dismissed — unless they consented to a search. The sheriff down there must know checkpoints like this are constitutionally questionable, but they can still ask people to consent, and they know how to phrase that request in such a way that people are likely to consent,he said.

The problem with these roadblocks and checkpoints

by uniformed highwaymen, which impose blanket screening of ordinary people by police and which intimidate or force everyone to submit to interrogation and searches, treating anyone who happens to be on a particular road as a presumptive criminal, who needs to prove her innocence to the police in order to be left alone to go about her own business, based on no probable cause whatever — and all in order to find and imprison a handful of nonviolent drug traffickers, who are violating absolutely nobody’s rights, who are doing a peaceful and productive service for willing customers, whose only crime

was to defy a senseless government prohibition on the kinds of chemicals that people may willingly put into their own bodies — the problem with that, I say, has nothing to do with whether these internal checkpoints and constrictions on peaceful people’s freedom of movement and security in their persons and effects, happen to be consistent or inconsistent with a fundamentalist reading of the words scribbled onto a 200-year-old piece of paper. The real problem is not that this kind of Ihre Papiere, bitte

treatment is unconstitutional; it’s that it’s tyrannical. Tyranny is bad enough whether or not the Nine can be convinced that it can be excused on a legal technicality, and the reasons why are moral, not constitutional. Even when cops can invent absurd technicalities in order to convince a judge (who is always willing to be convinced that another State employee was acting within bounds) that their extraction of searches through intimidation, coercion, and the inevitable recourse to the threat of arbitrary arrest on any of the countless vague laws that nobody can possibly avoid violating in daily life, all somehow amounts to consent.

And those of us who oppose the drug war, and the police state that has emerged in order to prosecute it, ought to be more clear and less timid about saying so. We don’t need The Law on our side to be right. If the Constitution allows that kind of brigandry and tyranny, then the Constitution itself is tyrannical. If the Constitution does not allow it, then it has been demonstrated as thoroughly as you please that the Constitution can do nothing effective to prevent it. In either case it is unfit to exist, and certainly undeserving of our deferential appeals.

In related news, holiday bloggers should keep in mind that there are only 7 more ranting days left before International Ignore the Constitution Day.

it’s tyrannical … and the reasons why are moral, not constitutional.

This is the central point, and part of the reason I became so disillusioned as a drug policy reform activist. Nobody was willing to stand up and attack the core immorality of the situation.

I found myself on Radley Balko’s blog once reading one of his usual brilliant dissections of some drug war atrocity or other, and what struck me — and what I commented about — was that the central reason (no pun intended) that all this is bad was omitted: because it’s wrong, not because procedure wasn’t followed or because laws weren’t adhered to.

Very strong post. There is no way out under the constitutional paradigm.

I always enjoy reading Spooner’s logic in a post. Thank you.

Devil’s advocate: okay, so my reasons for opposing the drug war are moral and not constitutional. But surely drug war opponents need to make constitutional arguments as well, no? Because otherwise, if everyone just gets to do what they think is moral, then a cop morally opposed to drug use and in favor of arresting drug addicts for moral reasons (as many people are) could go ahead and do so. Some shared basis of rules is necessary to stop that cop (or judge) from doing that; that’s what the Constitution represents. And that’s why, if we want to oppose the arrests of these drug users, we have to make Constitutional arguments: because we have to make arguments within the already-existing rules. Moral arguments can tell us why we should change the rules, but cops and judges don’t have the power to change the rules, only to enforce and/or interpret them, so to argue against current arrests (rather than to simply fight for repealing Drug War legislation)…it seems that we’re stuck with Constitutional arguments, as well as moral ones.

LadyVetinari,

If it does turn out that it’s worthwhile to make constitutional arguments in this context, then I think that at least part of my argument still stands: that people ought to at least to be making the moral argument against the police state measures that attend the drug war in addition to any constitutional arguments that they may make. Which, unfortunately, a lot of civil libertarians have been hesitant to do. (Probably because so many civil liberties outfits are run by lawyers. It’s good there are civil liberties lawyers out there, but the fact that it’s mainly lawyers speaking on behalf of civil liberties in public debate has resulted in most of the libertarian side of the debate being tilted towards legalism and appeals to the constitution and precedent, and away from moral suasion. Which is a problem, because if people aren’t already somewhat convinced of the evils of, say, random police checkpoints, appealing to Indianapolis v. Edmond either won’t convince them at all, or, if it will convince them, will convince them for entirely the wrong reasons (authoritarianism is wrong because the Authorities said so!). Either result will naturally tend towards what we have today, in which the constitution is consistently interpreted by the highest authorities as a document authorizing torture, military tribunals in peacetime, gun grabs, police checkpoints, etc. just so long as there is some legalistic technicality that legally-trained professionals can devise in order to make it O.K. For example, the cover of an undeclared and covertly prosecuted war with no defined enemy and nothing that would definitively count as either victory or defeat; or the excuse that a checkpoint is not really a drug checkpoint — as if arbitrarily blanket requirements for all motorists to stop at police checkpoints to get hassled by the highway patrol were somehow less tyrannical when the purpose is to force people to prove their sobriety and to force them to show their papers to the cops; and as if that kind of checkpoint didn’t really count as a stop-and-search drug checkpoint as long as the cops were using the right legal formulas to intimidate people into to a search without quite stepping on the judge’s toes; and as if that kind of checkpoint didn’t really count as a stop-and-search drug checkpoint if they just happened to have drug-sniffing dogs on site, to have chosen the site based on the reports they’d received about drug trafficking on that road; etc. etc. etc. The basic problem is that the whole debate rests on dickering over the right reading of the ipsissima verba of a legal text and several different relevant court rulings about that text; but government law enforcement is always going to have an advantage over you if the fight comes down to nothing more than dickering over legal technicalities, without any broader debate about the underlying moral principles that supposedly animate and justify those legal requirements; because government law enforcers work with the law every day, are more familiar than you are with manipulating it to get what they want; and, most importantly, enjoy a great deal of automatic deference from their fellow government employees on the bench, regardless of what the law actually says. Arguments based on authority without appeals to morality are, as a rule, always going to fall back into the most authoritarian understandings of what that authority requires. Which is part of the reason we are where we are today.

Now, if that’s right, the remaining question is whether constitutional appeals are useful at all, if accompanied by moral argument. With the Devil’s Advocate hat on, you worry:

But the issue isn’t that everyone should do whatever they think is moral; the issue is that everyone should do what really is moral. You might ask how I can convince someone to do what really is moral if their moral beliefs are different from mine; but the answer is that the way to do it is to give them moral arguments, of the kind I suggest against (e.g.) the drug war and the police state, which give reasons for them to change their moral views. If I try to short-circuit that process, by trying to show them that what they want to do is somehow illegal even if it is not immoral, then, depending on the person, either (a) I will just be giving them reasons to think that the law is tyrannical, since it forbids them to do the right thing, or else (b) I may convince them to conform to morality, but for the sake of authority rather than for the sake of morality, and so they will be doing so for the wrong reasons, and so reinforcing the very vice (authoritarianism and the subordination of the individual conscience to the dictates of the State) that my argument was supposedly intended to combat.

As a matter of history, I don’t think that the Constitution has successfully prevented cops or judges from using violence, up to and including lethal violence, against drug addicts. In fact it is currently interpreted as authorizing them to do so.

I agree that if you are in court, you have to deal with the already-existing rules, and should feel free to try and make these kind of constitutional arguments in order to (say) get the evidence against you thrown out, or otherwise get yourself off the hook.

But the kind of arguments that are prudent in a court-room context aren’t necessarily the kind of arguments that are best suited to public discourse outside of that context, such as in the columns of Drug War Chronicle. If your aim is to change the political culture, then I think it is generally very important not to rely just on legalistic arguments in order to do so. Partly because that strategy doesn’t actually usually work, and partly because, in the few cases where it does work, it works for the wrong reasons, and so tends to be an unreliable strategy, which produces Pyrrhic victories at the very best, and often produces only temporary victories that are soon swept away by a change in the laws or a change in the composition of the court.

Actually, I don’t think this is true. Cops and judges do have it in their power to change the rules — they can make any tyrannical law or government order a dead letter, simply by refusing to enforce it, by refusing to investigate or arrest, by throwing cases out of court, etc. I don’t hold out much hope for actually convincing a large number of cops to do this — especially not in the current political culture — even though there is the occasional heroic example even in the midst of the U.S. drug war. But it is important to remember that in revolutionary contexts, when the political culture is rapidly changing, has been radicalized, and traditionally constituted forms of coercive authority have been delegitimized and destabilized by the force of moral (not legalistic) arguments against them, there are lots of examples of cops finally stepping aside and refusing to carry out the orders that they were given. It’s always in their power to do so, but you’ll never convince many of them to do so unless and until you change the political culture by means of forceful, radicalizing moral arguments.

Does that help clarify?

On the last bit, about the power of cops to change the de facto rules by refusing orders, the recent example of Otpor in Serbia may be instructive. (Boldface added.)

RadGeek, you write:

Yes, this I agree with completely. As someone who has studied some law, though, I know how skeptical judges (and therefore lawyers who have to deal with those judges) tend to be when confronted with moral arguments in the absence of legal arguments: at best, they’ll respond by saying “Well, sure, the law is immoral, but if you choose to violate an immoral law then you should be willing to be arrested and punishd for it, so that the example of your arrest will show others how wrong the law is. That is the basic principle of civil disobedience, after all.” At worst, they’ll harrumph about how the law is the law for everyone and you can’t be your own judge.

Your distinction between the courtroom and the public sphere at large is well-made. The only issue I have with that is that, in the public sphere, so many people place huge importance on the concept of respect for the law as such. We can debate the merits of that–as an anarchist I think you’d say there are no merits to it–but if we want to convince these other people of the problems with the drug war, it helps to argue that, while drug laws might be laws, they contradict the principles embodied in the highest laws of our land, i.e. the Constitution. (We can also, simultaneously, make the moral arguments). You could argue that the Constitution does not embody these principles given that, as you point out, it’s currently interpreted as allowing lethal violence against drug addicts. But I’d say that’s because of the popularity of extreme conservative interpretations of the Constitution, and that most legal analysts think such interpretations are bunk, and really the plain meaning of the Constitution shows that those analysts are right.

I suppose there are three issues here: the first is whether or not there is such a thing as “moral reality.” My instincts say yes, but I’m not entirely sure how to defend it. The second issue is, whether or not there is “moral reality,” I can convince people of my morality through argument. And the third is, even given that there is a moral reality and that we can demonstrate it through argument, is it a good idea to encourage judges to enforce their moral judgments? It will be good when they’re right, but it will suck mightily when they’re wrong.

When it comes to the Drug War, I do think judges (and most people) are more likely to be right than wrong because most people can see the sheer cruelty of locking someone away for years because of a victimless crime. So I can maybe see that there would be a net positive in encouraging judges (and cops?) to make moral judgments on these issues. David Simon and Ed Burns, creators of the show “The Wire,” have gone on the record encouraging people selected for juries in drug trials to engage in jury nullification (e.g. refuse to convict drug addicts no matter what the evidence is). I support this wholeheartedly, although I have heard arguments that the better thing to do would be to declare during voir dire that you cannot possibly be on the jury because you do not believe in the drug laws (as that would not be a violation of the law, unlike jury nullification). The problem I have with that is, while masses of people refusing to be on drug trial juries would have a profound social effect, it might not help the actual drug addict being charged (unless it was impossible to find any twelve people willing to judge him).

Thank you for that Lakey quote. That’s quite fascinating, and I’ll concede that cops can in practice change the law. I suppose the question then is, what is the risk in encouraging cops to make their own moral judgments independently of the law? Are they more likely to be right or wrong? Because there’s nothing to stop cops from deciding that it’s immoral to protect abortion clinics from being bombed, for instance, and I could easily envision a pro-life campaign dedicated to convincing cops of that. The point of the law is to offer some predictability: written rules will be enforced, and you can depend on that, and you don’t have to worry about some cop deciding that the rules are immoral and screwing you over because of this. (Whether or not the law in any given place actually achieves this purpose is another matter).