On 6 December 1989, sixteen years ago today, Marc Lepine murdered 14 women at Montreal’s Ecole Polytechnique. He killed them because they were women; he went into an engineering class with a gun, ordered the men to leave, screamed I hate feminists

, and then opened fire on the women. He kept shooting, always at women, as he moved through the building, killing 14 women and injuring 8 before he ended the terror by killing himself.

6 December is a day of remembrance for the women who were killed. They were:

- Geneviève Bergeron, aged 21

- Hélène Colgan, 23

- Nathalie Croteau, 23

- Barbara Daigneault, 22

- Anne-Marie Edward, 21

- Maud Haviernick, 29

- Barbara Maria Klucznik, 31

- Maryse Leclair, 23

- Annie St.-Arneault, 23

- Michèle Richard, 21

- Maryse Laganière, 25

- Anne-Marie Lemay, 22

- Sonia Pelletier, 28; and

- Annie Turcotte, aged 21

I don’t have much to add today, except to repeat what I said last year:

The Montreal Massacre was horrifying and shocking. But we also have

to remember that it’s less unusual than we all think. Yes, it’s a

terrible freak event that some madman massacred women he had never

even met because of his sociopathic hatred. But every day women

are raped, beaten, and killed by men–and it’s usually not by

strangers, but by men they know and thought they could trust. They

are attacked just because they are women–because the men who

assault them believe that they have the right to control women’s

lives and their sexual choices, and to hurt them or force them if

they don’t agree. By conservative estimates, one out of every four women is raped or beaten by an intimate partner sometime

in her life. Take a moment to think about that. How much it is.

What it means for the women who are attacked. What it means for all

women who live in the shadow of that threat.

On what seems like an unrelated topic,

I’ve been asked before, and I’m sure I’ll be asked again, what it is that makes me so sympathetic to, and inspires me in, radical feminism, and Andrea Dworkin’s version of radical feminism specifically. That’s a question that gets tossed at anyone who expresses sympathy for or interest in Dworkin’s work, but I guess it’s supposed to be especially puzzling in my case, as someone who’s (1) male and (2) pretty stridently libertarian in my politics. There are a lot of things to say in response, but the one that means the most is to say that Andrea Dworkin takes violence against women seriously. What it means for violence, and the threat of violence, to be so pervasive, systematic, intense, and socially invisible or culturally excused. The demands that places on all of us. The urgency and seriousness of the struggle that it calls for. The fact that I’m male (and that I’ve had to make the painful realization of how often what I’ve said and what I’ve done hurt women, how much it was shaped by, and participated in, the same system of male supremacy that has hurt some of my dearest friends and family so badly) harldy overrides the fact that, well, what she says is true. (I know it’s true, because it’s happened to my friends.) And the fact that my politics are centrally concerned with a radical and comprehensive commitment to human freedom makes the insights offered by Andrea Dworkin (and Catharine MacKinnon and Susan Brownmiller and Robin Morgan and…) more, not less urgently needed. As I’ve written elsewhere (with my friend Roderick Long):

Brownmiller’s and other feminists’ insights into the

pervasiveness of battery, incest, and other forms of male violence

against women, present both a crisis and an opportunity for

libertarians. Libertarianism professes to be a comprehensive theory

of human freedom; what is supposed to be distinctive about

the libertarian theory of justice is that we concern ourselves with

violent coercion no matter who is practicing it—even

if he has a government uniform on. But what feminists have forced

into the public eye in the last 30 years is that, in a society

where one out of every four women faces rape or battery by an

intimate partner,

and where women are threatened or attacked by men who profess to

love them, because the men who attack them believe that being a man

means you have the authority to control women, male violence

against women is nominally illegal but nevertheless systematic,

motivated by the desire for control, culturally excused, and

hideously ordinary. For libertarians, this should sound eerily

familiar; confronting the full reality of male violence

means nothing less than recognizing the existence of a violent

political order working alongside, and independently of, the

violent political order of statism. As radical feminist

Catharine MacKinnon writes, “Unlike the ways in which men

systematically enslave, violate, dehumanize, and exterminate other

men, expressing political inequalities among men, men’s forms

of dominance over women have been accomplished socially as well as

economically, prior to the operation of the law, without express

state acts, often in intimate contexts, as everyday life” (1989,

p. 161). Male supremacy has its own ideological

rationalizations, its own propaganda, its own expropriation, and

its own violent enforcement; although it is often in league

with the male-dominated state, male violence is older, more

invasive, closer to home, and harder to escape than most

forms of statism. This means that libertarians who are

serious about ending all forms of political violence need to fight,

at least, a two-front war, against both statism and male supremacy

…

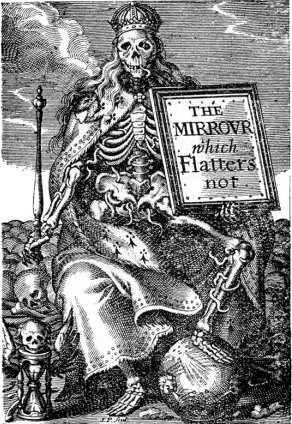

Here is the speech that Andrea Dworkin gave at the University of Montreal, a year and a day after the massacre:

Feminists should remember that while we often don’t take ourselves

very seriously, the men around us often do. I think that the way we

can honor these women who were executed, for crimes that they may

or may not have committed–which is to say, for political

crimes–is to commit every crime for which they were executed,

crimes against male supremacy, crimes against the right to rape,

crimes against the male ownership of women, crimes against the

male monopoly of public space and public discourse. We have to

stop men from hurting women in everyday life, in ordinary life,

in the home, in the bed, in the street, and in the engineering

school. We have to take public power away from men whether they

like it or not and no matter what they do. If we have to fight

back with arms, then we have to fight back with arms. One way or

another we have to disarm men. We have to be the women who stand

between men and the women they want to hurt. We have to end the

impunity of men, which is what they have, for hurting women in all

the ways they systematically do hurt us.

–Andrea Dworkin (1990): Mass Murder in Montreal, Life and Death, 105-114.

And, as I said last year:

To be serious about creating a free and just society, we have to

be serious about ending violence against women. As

Andrea Dworkin puts it (speaking about sexual assault),

I

want to see this men’s movement make a commitment to ending rape

because that is the only meaningful commitment to equality. It is

astonishing that in all our worlds of feminism and antisexism we

never talk seriously about ending rape. Ending it. Stopping it. No

more. No more rape. In the back of our minds, are we holding on to

its inevitability as the last preserve of the biological? Do we

think that it is always going to exist no matter what we do? All of

our political actions are lies if we don’t make a commitment to

ending the practice of rape. This commitment has to be political.

It has to be serious. It has to be systematic. It has to be public.

It can’t be self-indulgent.

And the same is true of every form

of everyday gender terrorism–stalking, battery, rape, murder. How

could we face Geneviève Bergeron, Hélène Colgan, Nathalie Croteau, Barbara Daigneault, Anne-Marie Edward,

Maud Haviernick, Barbara Maria Klucznik, Maryse Leclair, Annie St.-Arneault, Michèle Richard, Maryse Laganière,

Anne-Marie Lemay, Sonia Pelletier, Annie Turcotte, and tell them we did anything less?

Take some time to keep the 14 women who were killed in the Montreal massacre in your thoughts. If you have the money to give, make a contribution to your local battered women’s shelter. As Jennifer Barrigar writes:

Every year I make a point of explaining that I’m pointing the

finger at a sexist patriarchal misogynist society rather than

individual men. This year I choose not to do that. The time for

assigning blame

is so far in the past (if indeed there ever

was such a time), and that conversation takes us nowhere. This is

the time for action, for change. Remember Parliament’s 1991

enactment of the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence

Against Women — the glorious moment when every single womyn in

the House stood together and claimed this Day of Remembrance.

Remember what we can and do accomplish — all of us — when we work

together. It is time to demand change, and to act on that demand.

Let’s break the cycle of violence, and let’s do it now.

Remember. Mourn. Act.

Elsewhere