Refuge of Oppression #5: Twofer Tuesday edition

Here’s two pieces of correspondence that arrived within three hours of each other, on this past Tuesday. The first comes to us from Stasi

[sic!] in reply to GT 2008-01-28: The tall poppies, part 3, my recent article on the spread of opium poppies as a cash crop for impoverished farmers in southern Iraq:

From: stasi

To: Rad Geek

Date: Tue, 12 Feb 2008 1:45 PM

Subject: You Must be High: Tall Poppies, IIIHow can you even think that raising opium plants is a suitable way of making money to raise your family out of poverty. The only to benefit from drug trade are the high powered, high financed drug cartels.

Additionally, drug use (opium, heroin, etc) has been proven to have detrimental effects on individuals, families, and SOCIETIES. Let’s ALL start raising drug inducing plants to make money.

You MUST be high to think in such terms.

Well, I’m convinced.

Remember, impoverished farmers who grow opium poppies may think that growing a lucrative cash-crop and trading pain-killers to willing customers benefits them more than would starving themselves to grow unprofitable crops that meet the approval of U.S. narcs. But whatever they may think, the Stasi knows that the only people to benefit from the drug trade are high powered, high financed drug cartels.

How foolish of Iraqi farmers to think that the ability to provide for your family, rather than starving for the sake of U.S. government narco-diplomacy, would be a benefit worth counting. The Stasi certainly knows what their families want and need better than they do.

Later in the afternoon, I received this from the starr,

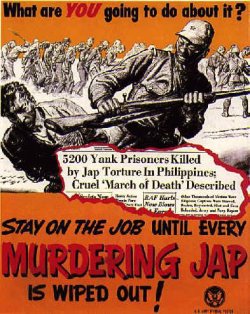

in reply to one of my posts on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in which over 200,000 Japanese civilians (about a third of the population of Nagasaki, and more than half of the population of Hiroshima) were burned alive, crushed to death, or otherwise killed, in a deliberate use of terror-bombing on heavily-populated city centers intended to force the unconditional surrender

of the Japanese government. Apparently my objection to this deliberate act of nuclear terrorism — the first and the only two cases in the history of the world — is the result of historical ignorance.

From: the starr

To: Rad Geek

Date: Tue, 12 Feb 2008, 4:23 PM

Subject: Atomic BombI read your article on the Atomic Bomb, and I must say, you don’t understand World War II at all. The use of the bomb was ABSOLUTELY NECESSARY. The Japanese were a brutal and evil empire and it had to be stopped. They slaughtered countless innocent people, not to mention Pearl Harbor. We urged them to surrender, but they wouldn’t. And they wouldn’t stop killing. The war would have continued for who knows how long and thousands upon thousands of more people would have died. The bomb was our only choice. You said that it killed thousands of innocent people. That’s true. But were the Japanese not doing the same? Did they not slaughter thousands of innocent people by invading other countries, including the completely un-called for attack on Pearl Harbor? There is no morality in warfare. It is foolish to try and equate them. You may want to do a little more research before you criticize the government’s carefully calculated decision.

If only I had understood World War II better before I wrote that post. I would have seen that, even though the Japanese military had already long been stopped

from any further expansion, and indeed broken, long before August 1945, absolute geopolitical triumph over the Japanese government, and the territorial conquest of Japan, was far more important than the irreplaceable lives of 200,000 or more innocent non-combatants. Indeed, it was important enough to justify or excuse deliberately targeting those 200,000 or more innocent non-combatants in order to force somebody else (the dictatorial clique tyrannizing Japan) to make the necessary political concessions. And little did I know that the Japanese

were all invading other countries and killing thousands of innocent people and refusing to surrender. I had foolishly thought that it was a small and unaccountable minority of the population of Japan who were extorting and tyrannizing the rest through the armed power of a military dictatorship. But since more research would have revealed that those 200,000 dead civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki (not to mention the hundreds of thousands of dead civilians from the over 100 Japanese cities that the U.S. Army attacked with low-altitude firebombing and conventional

high explosives) weren’t actually non-combatants after all, but were all running around with The Japanese as a whole, invading other countries and killing thousands of innocent people, well, I guess that’s that.

Normally, I would also have thought that if you have a true statement of the form There’s no morality in that,

that’s as good a reason as you could possibly find to draw the conclusion that you have an unconditional moral obligation to forswear ever engaging in that. This is another sure sign of my folly, ignorance or vice. One man’s reductio …

and all that; no doubt had I carefully calculated

like the Masters of War in the U.S. government, when the antecedent of that

is War,

it would become clear that what you actually have is a military obligation to sometimes forswear engaging in morality.

My bad.