Several months ago, Bill Patry created quite a stir when he shuttered his blog, where he’d spent four years promoting copyright law reform. One of his two chief reasons for the shut-down was despair at the state of copyright law:

2. The Current State of Copyright Law is too depressing

This leads me to my final reason for closing the blog which is independent of the first reason: my fear that the blog was becoming too negative in tone. I regard myself as a centrist. I believe very much that in proper doses copyright is essential for certain classes of works, especially commercial movies, commercial sound recordings, and commercial books, the core copyright industries. I accept that the level of proper doses will vary from person to person and that my recommended dose may be lower (or higher) than others. But in my view, and that of my cherished brother Sir Hugh Laddie, we are well past the healthy dose stage and into the serious illness stage. Much like the U.S. economy, things are getting worse, not better. Copyright law has abandoned its reason for being: to encourage learning and the creation of new works. Instead, its principal functions now are to preserve existing failed business models, to suppress new business models and technologies, and to obtain, if possible, enormous windfall profits from activity that not only causes no harm, but which is beneficial to copyright owners. Like Humpty-Dumpty, the copyright law we used to know can never be put back together again: multilateral and trade agreements have ensured that, and quite deliberately.

It is profoundly depressing, after 26 years full-time in a field I love, to be a constant voice of dissent. I have tried various ways to leaven this state of affairs with positive postings, much like television news shows that experiment with happy features.

I have blogged about great articles others have written, or highlighted scholars who have not gotten the attention they deserve; I tried to find cases, even inconsequential ones, that I can fawn over. But after awhile, this wore thin, because the most important stories are too often ones that involve initiatives that are, in my opinion, seriously harmful to the public interest. I cannot continue to be so negative, so often. Being so negative, while deserved on the merits, gives a distorted perspective of my centrist views, and is emotionally a downer.

— Bill Patry, The Patry Copyright Blog (2008-08-01): End of the Blog

In one sense, it’s hard not to sympathize. Existing copyright law has been more or less fully transformed into an openly wielded tool of perpetual corporate monopoly. The horizons of allowable debate over copyright policy, within the Beltway, stretch from one end of Disney’s boardroom to the other. Neither political party questions that the primary purpose of copyright law is to protect copyright-holders’ monopoly profit margins, and no serious politician would ever consider spending a dime of political capital on a suggestion that perhaps we should contain — let alone roll back — the hyperaggressive efforts of copyright monopolists to protect their broken business models, by using litigation and legal coercion to cripple every advance in digital technology, and locking down every last decibel of free speech in a corporate copyright containment field. Even if a politician did choose to stand up for the freedom to peacefully exchange, adapt, and redistribute ideas, it could hardly matter; she would be immediately drowned out by a chorus of Endangered Capitalist preservationists on both sides of the aisle. And even if she could be heard, any attempt she might make at a run towards reform would be promptly tripped up by the knotted tangle of multilateral trade agreements (NAFTA, CAFTA, the WTO), which (in the name of free trade

and private property rights–ha, ha) actually lock all the participating governments into a relentless commitment to granting and defending effectively perpetual government-granted monopolies, as part of their treaty obligations. There is no real hope of extricating U.S. government copyright law from this situation in any significant way; the pols and the Intellectual Protectionist lobby crossed that bridge a long time ago, and they made sure to burn it once they got to the other side.

Like I said: it’s hard not to sympathize. In fact, since my own views about copyright restrictions are far more radical than the ones Patry advances — I want them abolished immediately and completely; I think that any dose

of intellectual monopoly is a dose of poison — you think I’d be far more depressed than he is about the state of affairs. But the truth is that I’m not pessimistic at all about copyright. One of the main things that struck me, back when I first read Patry’s farewell post, is how much of a disconnect I felt between his picture of the legal scene, and the actual situation on the ground when it comes to copyright restrictions. In fact, even though everything Patry says about the legal situation is true, there’s never been a better time for being able to freely access the art and literature of the world. As a recent New York Times feature points out:

On the day last July when The Dark Knight

arrived in theaters, Warner

Brothers was ready with an ambitious antipiracy campaign that involved months

of planning and steps to monitor each physical copy of the film.

The campaign failed miserably. By the end of the year, illegal copies of the

Batman movie had been downloaded more than seven million times around the

world, according to the media measurement firm BigChampagne, turning it into

a visible symbol of Hollywood’s helplessness against the growing problem of

online video piracy.

The culprits, in this case, are the anonymous pirates who put the film online

and enabled millions of Internet users to view it. Because of widely available

broadband access and a new wave of streaming sites, it has become

surprisingly easy to watch pirated video online — a troubling development for

entertainment executives and copyright lawyers.

Hollywood may at last be having its Napster moment — struggling against the

video version of the digital looting that capsized the music business. Media

companies say that piracy — some prefer to call it digital theft

to

emphasize the criminal nature of the act — is an increasingly mainstream

pursuit. At the same time, DVD sales, a huge source of revenue for film studios,

are sagging. In 2008, DVD shipments dropped to their lowest levels in five

years. Executives worry that the economic downturn will persuade more users

to watch stolen shows and movies.

Young people, in particular, conclude that if it’s so easy, it can’t be

wrong,

said Richard Cotton, the general counsel for NBC Universal.

People have swapped illegal copies of songs, television shows and movies on

the Internet for years. The slow download process, often using a peer-to-peer

technology called BitTorrent, required patience and a modicum of sophistication

by users. Now, users do not even have to download. Using a search engine,

anyone can find free copies of movies, still in theaters, in a matter of minutes.

Classic TV, like every Seinfeld

episode ever produced, is also free for

the streaming. Some of these digital copies are derived from bootlegs, while

others are replicas of the advance review videos that studios send out before a

release.

TorrentFreak.com, a Web site based in Germany

that tracks which shows are most downloaded, estimates that each episode of

Heroes,

a series on NBC, is downloaded five million times, representing

a substantial loss for the network. (On TV, Heroes

averages 10 million

American viewers each week).

A wave of streaming sites, which allow people to start watching video

immediately without transferring a full copy of the movie or show to their hard

drive, are making it easier than ever to watch free Hollywood content online.

Many of these sites are located in countries with lackluster piracy enforcement

efforts, like China, and are hard to monitor, so media companies do not have a

clear sense of how much content is being stolen.

— Brian Stelter and Brad Stone, New York Times (2009-02-04): Digital Pirates Winning Battle With Studios

Of course, the New York Times has mistaken this for a problem;

but if you recognize that the Intellectual Protectionists’ restrictive business model is the real problem, what we’re now seeing is the solution. Not because the copyright laws have become even a little more liberal, but rather because they have become irrelevant to people’s daily lives. Even though everything Patry says about the legal situation is true, it becomes easier every day for me to find freely-shared copies of just about any song I could care to hear, or to find any number of supposedly copyrighted essays, available for free on the web, or to find any movie I could care to watch, whether it’s an old classic from the film-monopolist’s vaults, or a new release that just hit theaters. And because so much is so freely available, even officially-sanctified copies of copyrighted material are being dropped in price (typically below US $1.00 a pop) and DRM user-control schemes are being dropped one after another. Even though everything Patry says about the legal situation is true, the practical situation on the ground is remarkably good, and it’s getting better every day. Of course, things are far from perfect. Of course, lots of copyright-holders are still looking for a fight with people trying to exchange ideas without paying a premium for a license. And of course, the legal situation is such that they can get pretty nasty, if they scout you out come after you on the legal battlefield. But first they have to scout you out. First, they have to get you to fight them on the open ground. And every day, they are finding their efforts more and more impossible. No matter how many big guns they may bring to bear, when they try to fight us, they find that they are fighting a Myrmidon army that renders those weapons increasingly useless.

So why Bill Patry’s despair? If you want to see copyright restrictions liberalized, then it may be true that the words on a page in Washington are worse than they’ve ever been; but the facts on the ground are perhaps better than they’ve been at any other time in the history of the United States. And while there is no hope for revising those words for the better any time soon, the facts are changing for the better every day, all their lawyers and their lobbyists and their intergovernmental treaties notwithstanding — they are improving daily as technical problems are solved, as new sharing networks emerge, and as the problem of even identifying the competition, let alone shutting them down, becomes more and more overwhelming for the copyrightists’ rear-guard legal strategy.

Why despair, or even care about the legal situation at all, if the practical situation makes the law irrelevant? A law that cannot be enforced is as good as a a law that has been repealed, and that is where we’re headed, faster and faster every day, when it comes to the intellectual monopolists and their jealously guarded legal privileges.

Statists constantly accuse anarchists of being naive, or utopian, or infantile, because we so often question the value of playing the game

and working within the system.

But if this is supposed to be a strategy based on the empirical prospects for success — and not just on some kind of felt need to come off as properly Serious and Grown Up to the right sort of people — then let’s look at the facts, and let’s see what kind of activity actually offers proven results, and realistic hope for success in the future.

If you put all your hope for social change in legal reform, and if you put all your faith for legal reform in maneuvering within the political system, then to be sure you will find yourself outmaneuvered at every turn by those who have the deepest pockets and the best media access and the tightest connections. There is no hope for turning this system against them; because, after all, the system was made for them and the system was made by them. Reformist political campaigns inevitably turn out to suck a lot of time and money into the politics–with just about none of the reform coming out on the other end. But if you put your faith for social change in methods that ignore or ridicule their parliamentary rules, and push forward through grassroots direct action — if your hopes for social change don’t depend on reforming tyrannical laws, and can just as easily be fulfilled by widespread success at bypassing those laws and making them irrelevant to your life — then there is every reason to hope that you will see more freedom and less coercion in your own lifetime. There is every reason to expect that you will see more freedom and less coercion tomorrow than you did today, no matter what the law-books may say.

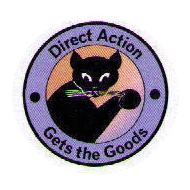

Counter-economics gets the goods.

See also: