Over My Shoulder #4: Paul Buhle’s Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland, and the Tragedy of American Labor

You know the rules. Here’s the quote. This is again from Paul Buhle’s Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland, and the Tragedy of American Labor.

Paradoxically and simultaneously, industrial unionism–though born of the radicalism of Toledo, Minneapolis, and San Francisco–became a new mode of enforcing the contract. Attempts to seize back the initiative from foremen and time-study experts were met, now, with directives from industrial union leaders to stay in line until a greivance could be properly negotiated. Soon, union dues would be deducted automatically from wages, so that officials no longer needed to bother making personal contact and monthly appeals to the loyalty of members.

Meany, treating industrial unionists at large as enemies, could not for many years grasp that events were bringing the CIO’s elected officials closer to him. He was steeped in a craft tradition to which the very idea of workers united into a single, roughly roughly egalitarian body hinted at revolutionary transformation. But many less conservative sectors were equally surprised by the course of the more democratic CIO unions toward the end of the 1930s. A triangle of government, business, and labor leadership brought about a compact that served mutual interest in stability, though often not in the interests of the workers left out of this power arrangement.

Not until 1937 did business unionism confirm its institutional form, when the Supreme Court upheld the Wagner Act. Now, a legitimate union (that is to say, a union legitimated by the National Labor Relation Board) with more than 50 percent of the vote in a union election became the sole bargaining agent for all. Unions stood on the brink of a membership gold-rush. The left-led Farm Equipment union could that same year, for instance, win a tremendous victory of five thousand workers at International Harvester in Chicago without a strike, thanks to the NLRB-sanctioned vote. But union leaders also prepared to reciprocate the assistance with a crackdown against membership indiscipline. The United Auto Workers, a case in point, arose out of Wobbly traditions mixed with a 1920s Communist-led Auto Workers Union and an amalgam of radicals’ efforts to work within early CIO formations. The fate of the industry, which fought back furiously against unionization, was set by the famed 1937 sit-down strikes centered in Flint, which seemed for a moment to bring the region close to class and civil war. Only the personal intercession of Michigan’s liberal Governor Murphy, it was widely believed, had prevented a bloodbath of employers’ armed goons retaking the basic means of production and setting off something like a class war. Therein lay a contradiction which the likes of George Meany could appreciate without being able to comprehend fully. The notorious willingness of UAW members to halt production until their greivances were met did not end because the union had employed the good offices of the goveronr (and the appeals of Franklin Roosevelt) to bring union recognition. On the one hand, a vast social movement of the unemployed grew up around the auto workers’ strongholds in Michigan, generating a sustained classwide movement of employed and unemployed, lasting until wartime brought near full employment. On the other hand, union leaders, including UAW leaders, swiftly traded off benefits for discipline in an uneven process complicated by strategic and often-changing conflicts within the political left.

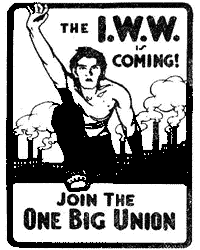

The continuing struggle for more complete democratic participation was often restricted to the local or the particularistic, and thanks to a long-standing tradition of autonomy, sometimes to insular circles of AFL veterans. For instance, in heavily French-Canadian Woonsocket, Rhode Island, a vibrant Independent Textile Union had sprung up out of a history of severe repression and the riotous 1934 general textile strike. The ITU remained outside the CIO and set about organizing workers in many industries across Woonsocket; then, after a conservatizing wartime phase, it died slowly with the postwar shutdown of the mills. To take another example, the All Workers Union of Austin, Minnesota–an IWW-like entity which would reappear in spirit during the 1980s as rebellious Local P-9 of the United Food and Commercial Workers–held out for several years in the 1930s against merger. A model par excellence of

horizontal,unionism with wide democratic participation and public support, the AWU (urged by Communist regulars and Trotskyists alike) willingly yielded its autonomy, and in so doing also its internal democracy, to the overwhelming influence of the CIO. In yet another case, the Progressive Miners of America, which grew out of a grassroots rebellion against John L. Lewis’s autocratic rule, attempted to place itself in th AFL that Lewis abandoned, on the basis of rank-and-file democracy with a strong dose of anti-foreign and sometimes anti-Semitic rhetoric. Or again: the AFL Seaman’s Union of the Pacific, reacting ferociously to Communist efforts to discipline the sea lanes, stirred syndicalist energies and like the PMA simultaneously drew upon a racist exclusionary streak far more typical of the AFL than the CIO.These and many less dramatic experiments died or collapsed into the mainstream by wartime. But for industrial unionism at large, the damage had already been done to the possibilities of resisting creeping bureaucratization. Indeed, only where union delegates themselves decreed safety measures of decentralization, as in the UAW in 1939 (against the advice of Communists and their rivals), did conventions emerge guaranteeing participation from below, to some significant degree.

–Paul Buhle, Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland, and the Tragedy of American Labor, 119-121.