Pet Peeves

There’s quite the debate raging over at Catallarchy, in reply to comments condemning Harry Truman as a terrorist as bad, or worse, than Osama bin Laden:

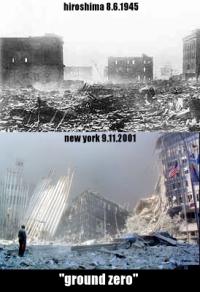

My view is the direct opposite of what they teach in government run schools. They teach that Truman’s action [the use of atomic weapons] was a heroic choice that saved many American lives. With a similar line of reasoning, a friend of mine argued that the massacre of civilians during war may be justified if the reward is high enough. He hesitated to make a judgment in the particular instance of Harry Truman’s wartime actions, claiming that the good of saving American troops at least partially offset the bad of incinerating Japanese homes and families.

Many other men have used logic similar to Truman’s supporters to justify attacking civilian targets to further national objectives. However, I don’t think my American friends would hesitate to condemn their actions because they don’t bat for the home team.

For example, the name

Osama bin Ladenhas taken its place among Hitler and Satan in the pantheon of evil. The reason? He thinks freeing the Arab world from Western imperial influences is important enough to sacrifice civilian lives. We might call him the Harry Truman of the Middle East.As most Americans condemn bin Laden for putting civilians in harm’s way, so too do I condemn Truman. If bin Laden is a

terrorist, then so is Truman. In fact, Truman’s actions are more indefensible because eventual victory was available through conventional military means. For bin Laden, direct military action, against the most feared armed force in all of history, is out of the question.Americans have a perverse and dangerous view of their place in the world. Until we realize that our civilians are not worth more than other country’s civilians and that our leaders do not operate within a sacred halo that allows them to turn ugly sins into holy acts, America will continue to be a source of great suffering.

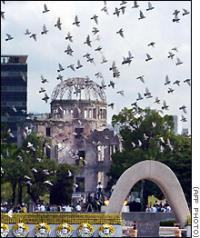

Now, I think that Jacob is right on here, and that the shameless apology for mass murder, as long as it happens under the Stars and Stripes, may very well be the most sickening feature in all of American education. But the fish I want to fry today is meta-ethical, not political, so if you want to argue about the massacres at Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Tokyo, etc., feel free to do so, but the point I want to call attention to is actually off to one side of the debate. Here’s a comment in the thread from Dave

, howling in protest (emphasis added):

Jacob’s post is about moral relativism gone out of control. Maybe next this

libertarianwill compare Timothy McVeigh to Murray Rothbard because both harbored anti-government feelings. Look at the passive posture he wants the United States to assume. …

And blah, blah, blah.

I pick this out because it highlights a pet peeve of mine. The Right–thanks to the influence of the Christian Right and fundamentalist ideas about the nature of secular modernism–have been throwing around the phrase moral relativism

in public debate over the past ten or twenty years, and every year that goes by they seem to get further and further from having any clue at all what it means. Here we have a particularly dramatic case in point: not only is there there is absolutely nothing in Jacob’s post which either entails or even suggests moral relativism. In point of fact, Jacob’s comments demand that moral relativism be rejected, and that moral principles be applied universally, rather than applied ad hoc depending on your relationship to the agent being judged.

It’s no sin not to know meta-ethical theory, but if you’re going to use the terms, you ought to know what they mean. Moral relativism

does not mean being lax about taboos that you shouldn’t be lax about

; far less does it mean drawing a mistaken comparison in ethics

. Moral relativism is the doctrine that one and the same action can be both right and wrong at the same time–that is, that questions of moral value can only be answered relative to some frame of reference that can change from one judgment to the next. For example, some people have believed (wrongly) that whether an action is right or wrong depends on whether the person making the moral judgment has a feeling of approval or disapproval towards it; other people have believed (also wrongly) that whether an action is right or wrong depends on whether or not the person making the moral judgment lives in a society in which the action is generally praised, generally condemned, or generally considered neutral. (For an excellent discussion of, and critical reply to, actual moral relativism, see Chapter III of G. E. Moore’s Ethics [1912].)

Now, Dave might think that Jacob’s moral principles (for example, that deliberately slaughtering thousands or hundreds of thousands of civilians in pursuit of your goals is wrong, no matter what) are mistaken. I don’t think they are, but that’s not the point here. The point is that Jacob is insisting on principled ethical judgments (even if you think the principles are wrong) and he is not claiming anywhere, ever, that the applicability of those principles is relative to the speaker’s feelings, or culture, or relation to the person carrying out the slaughter, or relation to the victims, or anything of the sort. Quite the contrary; he’s insisting that moral principles, which he claims we insist on in bin Laden’s case, ought to be applied absolutely and for everyone. That’s an outright rejection of relativism and the excuses for atrocities that relativism so happily provides.

On the other hand, I can’t say the same for these comments:

If you don’t believe that your country’s citizens are

worth morethan the citizens of other countries — that is, entitled to live even if it means the death of citizens of other countries — I don’t want to be in the same foxhole with you.

But of course the comments come not from Jacob, but from the hawkish Tom

, in protest of Jacob’s point. The implied conclusion — that subjects of other States shouldn’t be treated as though they have as much of a right to life as the subjects of your own State — is a textbook case of moral relativism. (Specifically, in this case, the claim that fundamental moral obligations, like the rights of innocents not to be burned alive as a sacrifice for others, can only be decided relative to the relationship between the you and the victim–if you are subjects of the same State then it is not O.K., but if you are subjects of different States, then anything up to and including dropping a fucking nuclear bomb on their heads is, apparently, acceptable.) Maybe Jacob’s principles are right and maybe they’re wrong; but he is employing principles, and insisting that they are universally binding. Tom, on the other hand, is explicitly stating that moral principles are binding relative to one group of people and mere breath relative to another. Yet it is Jacob, not Tom, who is denounced as a moral relativist

; this is nothing but darkening counsel with words without knowledge.

The kind of argument that Tom uses is, of course, a method of excuse used all the time by the Right: the idea that any means at all are acceptable in warfare, because our moral obligations end at borders on a map, and so the pursuit of victory

can trump any and every other moral consideration. Of course, just saying that a view is relativist is not the same thing as saying that it is false; maybe there are some good arguments for relativism. I haven’t found any, and I think there are decisive arguments against it, but it’s an open philosophical topic. But my concern here is about the proper use of terms, and about consistency; if you are going to support a bloody and unapologetic form of relativism, then you had better argue for it, and you had better not pretend that you’re opposed to it. Yet it seems that somehow the self-appointed arch-nemeses of moral relativism never do get around to condemning this sort of blatant disregard for universality in ethics–perhaps because their situation is as the Prophet has written: We have met the enemy, and they is us.