The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

This happened 95 years ago today, on 25 March 1911.

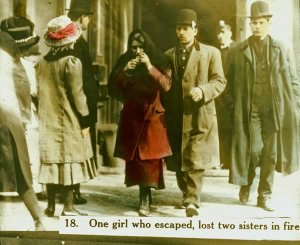

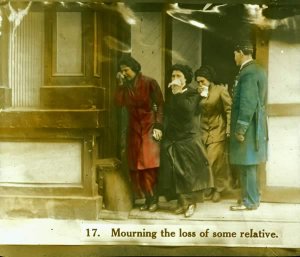

Near closing time on Saturday afternoon, March 25, 1911, a fire broke out on the top floors of the Asch Building in the Triangle Waist Company. Within minutes, the quiet spring afternoon erupted into madness, a terrifying moment in time, disrupting forever the lives of young workers. By the time the fire was over, 146 of the 500 employees had died. The survivors were left to live and relive those agonizing moments. …

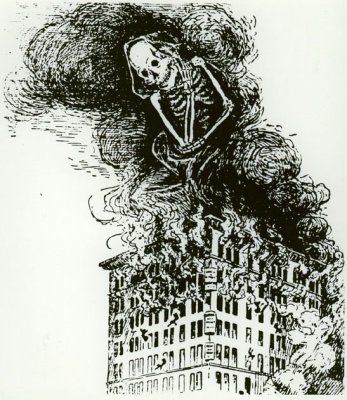

At 4:40 o’clock, nearly five hours after the employes in the rest of the building had gone home, the fire broke out. The one little fire escape in the interior was resorted to by any of the doomed victims. Some of them escaped by running down the stairs, but in a moment or two this avenue was cut off by flame. The girls rushed to the windows and looked down at Greene Street, 100 feet below them. Then one poor, little creature jumped. There was a plate glass protection over part of the sidewalk, but she crashed through it, wrecking it and breaking her body into a thousand pieces.

Then they all began to drop. The crowd yelled

Don’t jump!but it was jump or be burned the proof of which is found in the fact that fifty burned bodies were taken from the ninth floor alone.… Messrs. Harris and Blanck were in the building, but the escaped. They carried with the Mr. Blanck’s children and a governess, and they fled over the roofs. Their employes did not know the way, because they had been in the habit of using the two freight elevators, and one of these elevators was not in service when the fire broke out.

Survivors recounted the horrors they had to endure, and passers-by and reporters also told stories of pain and terror they had witnessed. The images of death were seared deeply in their mind’s eyes.

Many of the Triangle factory workers were women, some as young as 15 years old. They were, for the most part, recent Italian and European Jewish immigrants who had come to the United States with their families to seek a better life. Instead, they faced lives of grinding poverty and horrifying working conditions. As recent immigrants struggling with a new language and culture, the working poor were ready victims for the factory owners. For these workers, speaking out could end with the loss of desperately needed jobs, a prospect that forced them to endure personal indignities and severe exploitation. Some turned to labor unions to speak for them; many more struggled alone. The Triangle Factory was a non-union shop, although some of its workers had joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.

New York City, with its tenements and loft factories, had witnessed a growing concern for issues of health and safety in the early years of the 20th century. Groups such as the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and the Womens’ Trade Union League (WTUL) fought for better working conditions and protective legislation. The Triangle Fire tragically illustrated that fire inspections and precautions were woefully inadequate at the time. Workers recounted their helpless efforts to open the ninth floor doors to the Washington Place stairs. They and many others afterwards believed they were deliberately locked– owners had frequently locked the exit doors in the past, claiming that workers stole materials. For all practical purposes, the ninth floor fire escape in the Asch Building led nowhere, certainly not to safety, and it bent under the weight of the factory workers trying to escape the inferno. Others waited at the windows for the rescue workers only to discover that the firefighters’ ladders were several stories too short and the water from the hoses could not reach the top floors. Many chose to jump to their deaths rather than to burn alive.

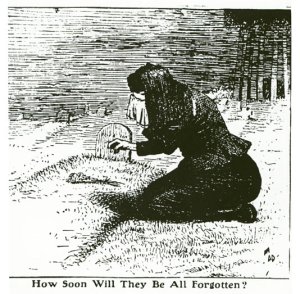

But the truth is that they had already been forgotten, all of them, until that terrible day 95 years ago. They were treated as the living dead: their lives, their dignity, and their precious humanity all forgotten by bosses who lived off their work while imprisoning them and leaving them to burn. By a predatory State that defended the bosses’ Law and the bosses’ Order by mercilessly attacking every attempt to challenge and resist. By the self-proclaimed progressives, by the comfortable and philanthropic, the good citizens who reacted with a shrug of killing indifference until it was far, far too late.

Our duty is to remember, or more precisely, not to forget them anymore. Never to forget them. Never again. Neither them, nor any of our other fellow workers.

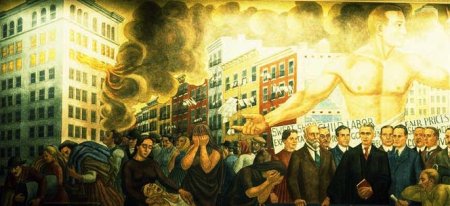

Mural by Ernest Fiene (1938) for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. …This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death.

We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us–warning that we must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.