Sheldon Richman recently posted to on the Bush gang’s palavering and depraved indifference to the life of Lebanese civilians. It’s a good post; you should read it. Along the way, he said this:

Translation: The killing and maining of Lebanese and Israelis shouldn’t stop until Israel is ready for it to stop.

That is moral depravity, if anything is.

In the comments section, E. Simon

replied:

So would your omission of the implication, that the cessation of hostilities not be constrained according to whether or not Nasrallah and his supporters are allowed to kill and maim Israelis, be an example of intellectual depravity?

Given that he’s so awfully concerned about innocent people being killed and maimed, I asked E. Simon the following, linking to my post on Proportionality:

And just how many unrelated third parties do you think the IDF can legitimately kill or maim in the process of retaliating against Nasrallah and his supporters

?

Here’s the answer, such as it is:

That being said, I think your question is a good one, because ideally, I would like to see NO unrelated third parties

hurt. Therefore, there is no good way to answer it since it would suggest legitimizing the ascription of a military

debit or financial value to the loss of a life whose inherent worth is — otherwise — incalculable. And yet, the use

of Israel’s military will prevent Hizbullah from intentionally causing the loss of similarly incalculably valuable Israeli

lives. But Israel is not responsible for Lebanon’s failures in necessitating that most unfortunate decision.

There are costs, no doubt. But the costs of not thusly, and appropriately disincentivizing against murder are much

riskier, given the total analysis.

Now, I’d like to note that this is a complete evasion of the question. (The fact that you wave your hands at the higher mysteries and heart-rending impossibility of answering a question does not mean that you haven’t evaded it; it just means that you’ve offered a poetical apology for the evasion.) As I note further down in the thread:

I’ve accused you of dodging the issue because if you do not have an answer to that question, then you can have

absolutely no moral basis for endorsing the war. If you don’t even have a ballpark estimate of what a tolerable

civilian body count is, then you have no idea whether or not the killing and maiming of innocents has gone beyond

the limits of proportional self-defense. And if you don’t know that then you don’t know whether or not the war is

legitimate self-defense or a massacre. If you treat the question as some higher mystery beyond your ken, then

you have thereby admitted that you have no idea whatever whether justice demands that the IDF continue or that

it relent.

If, however, you profess not to be able to answer the question, but then turn around and continue supporting the

war, particularly with polysyllabic hand-waving at pacifying abstractions such as collateral damage

and

appropriately disincentivizing,

then what I have to conclude is that you are quite satisfied with the level of

killing, burning, bombing, and maiming being inflicted on innocents, but that you’d rather not say so because it

would sound too brutal coming from your lips.

You can follow the argument on its merits through the rest of the thread; as far as that goes, I’m willing to just say We Report, You Decide

for now. But I do want to make a remark about a matter of style, rather than substance here. That may seem petty, or underhanded, and in any case irrelevant. But it’s not: the style in which people say the things about war that E. Simon wants to say here is itself a very important part of what allows them to utter the substantial position that they end up uttering. Let’s look at that again:

That being said, I think your question is a good one, because ideally, I would like to see NO unrelated third parties

hurt. Therefore, there is no good way to answer it since it would suggest legitimizing the ascription of a military

debit or financial value to the loss of a life whose inherent worth is — otherwise — incalculable. And yet, the use

of Israel’s military will prevent Hizbullah from intentionally causing the loss of similarly incalculably valuable Israeli

lives. But Israel is not responsible for Lebanon’s failures in necessitating that most unfortunate decision.

There are costs, no doubt. But the costs of not thusly, and appropriately disincentivizing against murder are much

riskier, given the total analysis.

My short response would be to offer some suggestions about where E. Simon can take his total analysis

. Fortunately, George Orwell already made the remarks I’d like to make about this passage, and much more eloquently than I could:

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of

British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed

be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with

the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism,

question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants

driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is

called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no

more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are

imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps:

this is called elimination of unreliable elements. Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without

calling up mental pictures of them. Consider for instance some comfortable English professor defending Russian

totalitarianism. He cannot say outright, I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results

by doing so.

Probably, therefore, he will say something like this:

While freely conceding that the Soviet regime exhibits certain features which the humanitarian may be inclined to

deplore, we must, I think, agree that a certain curtailment of the right to political opposition is an unavoidable

concomitant of transitional periods, and that the rigors which the Russian people have been called upon to

undergo have been amply justified in the sphere of concrete achievement.

The inflated style itself is a kind of euphemism. A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring

the outline and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap

between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted

idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink. In our age there is no such thing as keeping out of politics.

All

issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred, and schizophrenia. When

the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer….

— George Orwell, Politics and the English Language (1946)

War survives because people don’t talk about war, but rather about something else, using an inflated jargon that they have mostly nicked from military communication (both internally, and through their press flacks). That jargon, and the style that goes with it, is more or less deliberately calculated to obscure and degrade thought, because to think and to speak, really and seriously, about what war does to people, would be to destroy any hope of moral and political legitimacy for any kind of modern campaign.

I’m told, incidentally, that my mentioning this, and my using harsh words in my own remarks, shows a lack of civility, open-mindedness, and maturity. But if civility and maturity mean whitewashing the killing and maiming of real people with real lives (with or without incalculable value

being sentimentally ascribed to them) into costs

to be assessed along with the risks

involved in not setting up the appropriate incentives,

as you do the total analysis

over the dispensability of other people’s lives and livelihoods, then civility and maturity and open-mindedness can go straight to hell, and take the civil

warmakers and war apologists right along with them.

Further reading:

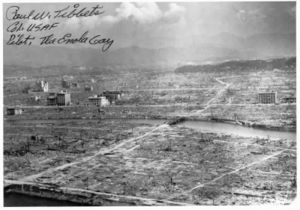

Sixty-one years ago today, at 8:15am in the morning, Thomas Ferebee, acting under the direct command of Paul Tibbets, on the orders of the United States government, dropped an atomic bomb over the city center of Hiroshima, Japan. When the bomb was dropped the city had a population of about 255,000 people. About 70,000–80,000 people were instantly killed by the shockwave, fireball, and radiation. By the end of 1945, tens of thousands more had died from their wounds, from radiation sickness, and from cancer related to the radioactivity. It’s estimated that about 140,000 people — more than half the population of the city — died in the nuclear massacre. The overwhelming majority of people killed were civilians: Hiroshima had only a couple of relatively unimportant military bases, and they were located on the edges of town, miles away from ground zero in the central city.

Sixty-one years ago today, at 8:15am in the morning, Thomas Ferebee, acting under the direct command of Paul Tibbets, on the orders of the United States government, dropped an atomic bomb over the city center of Hiroshima, Japan. When the bomb was dropped the city had a population of about 255,000 people. About 70,000–80,000 people were instantly killed by the shockwave, fireball, and radiation. By the end of 1945, tens of thousands more had died from their wounds, from radiation sickness, and from cancer related to the radioactivity. It’s estimated that about 140,000 people — more than half the population of the city — died in the nuclear massacre. The overwhelming majority of people killed were civilians: Hiroshima had only a couple of relatively unimportant military bases, and they were located on the edges of town, miles away from ground zero in the central city.