On traditionalism: how homoeroticism flourished in medieval Persia, and how political homophobia came to be imported from the West

One of the difficulties in having serious conversations about cultural conservatism — both here and abroad — is how often it turns out that what the so-called conservative

wishes to preserve or to restore the conditions of a past that never existed. When this kind of mythistory is used to pass off modern authoritarian’s political desiderata as if they were accurate representations of history, both the pseudotraditionalists, and their self-styled progressive

opponents, tend to take for granted that history must have been whatever modern political conservatives want it to have been; they just argue over whether that history is a good thing or a bad thing, and so whether to join in the march of Progress or to stand athwart history yelling Stop!

In reality, though, antiquity is always a much more complicated affair than simple-minded political progress narratives would make it. And often it is exactly the opposite. Take, for instance, the story of queer eroticism in Iran, where — setting aside the propaganda of the Ayatollahs and the colonialist liberals both — it becomes clear that medieval Iran was full of passionate expressions of same-sex eroticism and same-sex romantic love, and that political homophobia, far from being an ingrown feature of traditional culture or religion, is in fact a colonial import, which came into Iranian political culture mainly through the modernizing ideologies of Marxism and Westernizing progressive nationalism.

When Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad made his infamous claim at a September 2007 Columbia University appearance that

In Iran, we don’t have homosexuals like in your country,the world laughed at the absurdity of this pretense.Now, a forthcoming book by a leading Iranian scholar in exile, which details both the long history of homosexuality in that nation and the origins of the campaign to erase its traces, not only provides a superlative reply to Ahmadinejad, but demonstrates forcefully that political homophobia was a Western import to a culture in which same-sex relations were widely tolerated and frequently celebrated for well over a thousand years. Sexual Politics in Modern Iran, [by Janet Afary,] to be published at the end of next month by Cambridge University Press, is a stunningly researched history and analysis of the evolution of gender and sexuality that will provide a transcendent tool both to the vibrant Iranian women’s movement today fighting the repression of the ayatollahs and to Iranian same-sexers hoping for liberation from a theocracy that condemns them to torture and death.

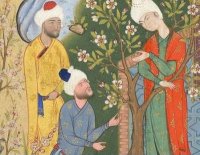

In her new book, Afary’s extensive section on pre-modern Iran, documented by a close reading of ancient texts, portrays the dominant form of same-sex relations as a highly-codified

status-defined homosexuality,in which an older man — presumably the active partner in sex — acquired a younger partner, or amrad. . . . Afary dissects howclassical Persian literature (twelfth to fifteenth centuries)…overflowed with same-sex themes (such as passionate homoerotic allusions, symbolism, and even explicit references to beautiful young boys.)This was true not only of the Sufi masters of this classical period but ofthe poems of the great twentieth-century poet Iraj Mirza (1874-1926)… Classical poets also celebrated homosexual relationships between kings and their pages.Afary also writes that

homosexuality and homoerotic expressions were embraced in numerous other public spaces beyond the royal court, from monasteries and seminaries to taverns, military camps, gymnasiums, bathhouses, and coffeehouses… Until the mid-seventeenth century, male houses of prostitution (amrad khaneh) were recognized, tax-paying establishments.. . . Unmistakably lesbian sigeh courtship rituals, which continued from the classical period into the twentieth century, were also codified:

Tradition dictated that one [woman] who sought another asAs late as the last half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th,sisterapproached a love broker to negotiate the matter. The broker took a tray of sweets to the prospective beloved. In the middle of the tray was a carefully placed dildo or doll made of wax or leather. If the beloved agreed to the proposal, she threw a sequined white scarf (akin to a wedding veil) over the tray… If she was not interested, she threw a black scarf on the tray before sending it back.Iranian society remained accepting of many male and female homoerotic practices… Consensual and semi-open pederastic relations between adult men and amrads were common within various sectors of society.What Afary terms aromantic bisexualityborn in the classical period remained prevalent at court and among elite men and women, anda form of serial love (‘eshq-e mosalsal) was commonly practiced [in which] their love could shift back and forth from girl to boy and back to girl.In a lengthy section of her book entitled

Toward a Westernized Modernity,Afary demonstrates how the trend toward modernization which emerged during the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 and which gave the Persian monarchy its first parliament was heavily influenced by concepts harvested from the West.One of her most stunning revelations is how an Azeri-language newspaper edited and published in the Russian Caucuses, Molla Nasreddin (or MN, which appeared from 1906 to 1931) influenced this Iranian Revolution with a

significant new discourse on gender and sexuality,sharing Marx’s well-documented contempt for homosexuals. With an editorial board that embraced Russian social democratic concepts, including women’s rights, MN was alsothe first paper in the Shi’i Muslim world to endorse normative heterosexuality,echoing Marx’s well-documented contempt for homosexuality. Afary writes thatthis illustrated satirical paper, which circulated among Iranian intellectuals and ordinary people alike, was enormously popular in the region because of its graphic cartoons.MN conflated homosexuality and pedophilia, and attacked clerical teachers and leaders for

molesting young boys,played upon feelings ofcontemptfor passive homosexuals, suggested that elite men who kept amrad concubineshad a vested interested in maintaining the (male) homosocial public spaces where semi-covert pederasty was tolerated,andmocked the rites of exchanging brotherhood vows before a mollah and compared it to a wedding ceremony.It was in this way that a discourse of political homophobia developed in Europe, which insisted that only heterosexuality could be the norm, was introduced into Iran.MN‘s attacks on homosexuality

would shape Iranian debates on sexuality for the next century,and itbecame a model for several Iranian newspapers of the era,which echoed its attacks on the conservative clergy and leadership for homosexual practices. In the years that followed,Iranian revolutionaries commonly berated major political figures for their sexual transgressions,andrevolutionary leaflets accused adult men of having homosexual sex with other adult men,of thirty-year-olds propositioning fifty-year-olds and twenty-year-olds propositioning forty-year-olds, right in front of the Shah.Some leaflets repeated the old allegation that major political figures had been amrads in their youth.. . . The expansion of radio, television, and print media in the 1940s — including a widely read daily, Parcham, published from 1941 by Kasravi’s Pak Dini movement — resulted in a nationwide discussion about the evils of pederasty and, ultimately, in significant official censorship of literature. References to same-sex love and the love of boys were eliminated in textbooks and even in new editions of classical poetry.

Classical poems were now illustrated by miniature paintings celebrating heterosexual, rather than homosexual, love and students were led to believe that the love object was always a woman, even when the text directly contradicted that assumption,Arafy writes.In the context of a triumphant censorship that erased from the popular collective memory the enormous literary and cultural heritage of what Afary terms

the ethics of male lovein the classical Persian period, it is hardly surprising as Afary earlier noted in Foucault and the Iranian Revolution that the virulence of the current Iranian regime’s anti-homosexual repression stems in part from the role homosexuality played in the 1979 revolution that brought the Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers to power.In that earlier work, she and her co-author, Kevin B. Anderson, wrote:

There is… a long tradition in nationalist movements of consolidating power through narratives that affirm patriarchy and compulsory heterosexuality, attributing sexual abnormality and immorality to a corrupt ruling elite that is about to be overthrown and/or is complicit with foreign imperialism ….— Doug Ireland, Direland (2009-02-27): Iran’s Hidden Homosexual History

(Via Jesse Walker 2009-03-09.)