Mary Daly’s turn-the-concept-inside-out phrase, The Sisterhood of Man

seems not only a hope but a dynamic actuality–since it’s grounded not in abstract notions of cooperation but in survival need, not in static posture but in active gesture, not in vague sentiments of similarity but in concrete experience shared to an astonishing degree, despite cultural, historical, linguistic, and other barriers. Labor contractions feel the same everywhere. So does rape and battery. I don’t necessarily always agree with many feminists that women have access to some mysteriously inherent biological nexus, but I do believe that Elizabeth Cady Stanton was onto something when she signed letters, Thine in the bonds of oppressed womanhood

(italics mine). Let us hope–and act to ensure–that as women break those bonds of oppression, the process of freeing the majority of humanity will so transform human consciousness that women will not use our freedom to be isolatedly individuated as men have done. In the meanwhile, the bonds do exist; let’s use them creatively.

Not that the mechanistic universe inhabited by the family of Man takes notice of this quarky interrelationship between the hardly visible subparticles that merely serve to keep Man and his [sic] family alive. No, such particles are unimportant, fantastical, charming perhaps (as quarks or the fair sex

tend to be). But they are to be taken no more seriously than fairytales.

Yet if Hans Christian Andersen characters so diverse as the Little Mermaid, the Robber Girl, the Snow Queen, and the Little Match Girl had convened a meeting to discuss ways of bettering their condition, one could imagine that the world press would cover that as a big story. When something even more extraordinary, because more real, happened in Andersen’s own city for three weeks during July 1980, it barely made the news.

Approximately ten thousand women from all over the planet began arriving in Copenhagen, Denmark, even before the formal opening on July 14 of the United Nations Mid-Decade World Conference for women. The conference was to become a great, sprawling, rollicking, sometimes quarrelsome, highly emotional, unashamedly idealistic, unabashedly pragmatic, visionary family reunion. In 1975, the U.N. had voted to pay some attention to the female more-than-half of the human population for one year–International Women’s Year–but extended the time to a decade after the indignant outcry of women who had been living, literally, in the International Men’s Year

for approximately ten millennia of patriarchy. Still, here we were, in the middle of our

decade, in Copenhagen. We came in saris and caftans, in blue jeans and chadors, in African geles, pants-suits, and dresses. We were women with different priorities, ideologies, political analyses, cultural backgrounds, and styles of communication. The few reports that made it into the U.S. press emphasized those differences, thereby overlooking the big story–that these women forged new and strong connections.

There were two overlapping meetings in Copenhagen. One was the official U.N. conference–which many feminists accurately had prophesied would be more a meeting of governments than of women. Its delegates were chosen by governments of U.N. member states to psittaceously repeat national priorities–as defined by men.

The official conference reflected the government orientation: many delegations were headed by men and many more were led by safe

women whose governments were certain wouldn’t make waves. This is not to say that there weren’t some real feminists tuckd away even in the formal delegations, trying gallantly to influence their respective bureaucracies towards more human concern with actions that really could better women’s lives. But the talents of these sisters within

were frequently ignored or abused by their own delegations for political reasons.

A case in point was the U.S. delegation, which availed itself greedily of all the brilliant and unique expertise of Koryne Horbal (then U.S. representative to the U.N. Commission on the Status of Women), and of all the groundwork she had done on the conference for the preceding two years–including being the architect of CEDAW, the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women–but denied her press visibility and most simple courtesies because she had been critical of the Carter administration and its official policies on women. But Horbal wasn’t the only feminist within.

There were New Zealand’s member of Parliament, the dynamic twenty-eight-year-old Marilyn Waring, and good-humored Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo, former prime minister of Portugal, and clever Elizabeth Reid of Australia–all of them feminists skilled in the labyrinthian ways of national and international politics, but with priority commitment to populist means of working for women–who still managed to be effective inside and outside the structures of their governments.

The other

conference, semiofficially under U.N. aegis, was the NGO (Non-Governmental Organization) Forum. It was to the Forum that ordinary folks

came, having raised the travel fare via their local women’s organizations, feminist alternative media, or women’s religious, health, and community groups. Panels, workshops, kaffeeklatsches, cultural events, and informal sessions abounded.

Statements emerged and petitions were eagerly signed: supporting the prostitutes in S?@c3;a3;o Palo, Brazil, who that very week, in an attempt to organize for their human rights, were being jailed, tortured, and, in one case, accidentally

executed; supporting Arab and African women organizing against the practice of female genital mutilation; supporting U.S. women recently stunned by the 1980 Supreme Court decision permitting federal and state denial of funds for medical aid to poor women who need safe, legal abortions–thus denying the basic human right of reproductive freedom; supporting South African women trying to keep families together under the maniacal system of apartheid; supporting newly exiled feminist writers and activists from the U.S.S.R.; supporting women refugees from Afghanistan, Campuchea [Cambodia], Palestine, Cuba, and elsewhere.

Protocol aside, the excitement among women at both conference sites was electric. If, for instance, you came from Senegal with a specific concern about rural development, you would focus on workshops about that, and exchange experiences and how-to’s with women from Peru, India–and Montana. After one health panel, a Chinese gynecologist continued talking animatedly with her scientific colleague from the Soviet Union–Sino-Soviet saber-rattling forgotten or transcended.

Comparisons developed in workshops on banking and credit between European and U.S. economists and the influential market women of Africa. The list of planned meetings about Women’s Studies ran to three pages, yet additional workshops on the subject were created spontaneously. Meanwhile, at the International Women’s Art Festival, there was a sharing of films, plays, poetry readings, concerts, mime shows, exhibits of painting and sculpture and batik and weaving, the interchanging of art techniques and of survival techniques. Exchange subscriptions were pledged between feminist magazines in New Delhi and Boston and Tokyo, Maryland and Sri Lanka and Australia. And everywhere the conversations and laughter of recognition and newfound friendships spilled over into the sidewalks of Copenhagen, often until dawn.

We ate, snacked, munched–and traded diets–like neighbor women, or family. A well-equipped Argentinian supplied a shy Korean with a tampon in an emergency. A Canadian went into labor a week earlier than she’d expected, and kept laughing hilariously between the contractions, as she was barraged with loving advice on how to breathe, where to rub, how to sit (or stand or squat), and even what to sing–in a chorus of five languages, while waiting for the prompt Danish ambulance. North American women from diverse ethnic ancestries talked intimately with women who still lived in the cities, towns, and villages from which their own grandmothers had emigrated to the New World.

We slept little, stopped caring about washing our hair, sat on the floor, and felt at home with one another.

Certainly, there were problems. Simultaneous translation facilities, present everywhere at the official conference, were rarely available at the grass-roots forum. This exacerbated certain sore spots, like the much-ballyhooed Palestinian-Israeli conflict, since many Arab women present spoke Arabic or French but not English–the dominant language at the forum. That conflict–played out by male leadership at both the official conference and the forum, using women as pawns in the game–was disheartening, but not as bad as many of us had feared.

The widely reported walkout

of Arab women during Madam Jihan Sadat’s speech at the conference was actually a group of perhaps twenty women tiptoeing quietly to the exit. This took place in a huge room packed with delegates who–during all the speeches–were sitting, standing, and walking about to lobby loudly as if on the floor of the U.S. Congress (no one actually listens to the speeches; they’re for the recrd).

Meanwhile, back at the forum, there was our own invaluable former U.S. congresswoman Bella Abzug (officially unrecognized by the Carter-appointed delegation but recognized and greeted with love by women from all over the world). Bella, working on coalition building, was shuttling between Israelis and Arabs. At that time, Iran was still holding the fifty-two U.S. hostages, but Bella accomplished the major miracle of getting a pledge from the Iranian women that if U.S. mothers would demonstrate in Washington for the shah’s ill-gotten millions to be returned to the Iranian people (for the fight against women’s illiteracy and children’s malnutrition), then the Iranian women would march simultaneously in Teheran for the hostages to be returned home to their mothers.

Bella’s sensitivity and cheerful, persistent nudging on this issue caused one Iranian woman to throw up her hands, shrug, and laugh to me, What is with this Bella honey

person? She’s wonderful. She’s impossible. She’s just like my mother.

The conference, the forum, and the arts festival finally came to an end. Most of the official resolutions were predictably bland by the time they were presented, much less voted on. Most of the governments will act on them sparingly, if at all. Consequently, those women who went naively trusting that the formal U.N. procedures would be drastically altered by such a conference were bitterly disappointed. But those of us who went with no such illusions, and who put not our trust in patriarchs, were elated. Because what did not end at the closing sessions isthat incredible networking

–the echoes of all those conversations, the exchanged addresses–and what that will continue to accomplish.

— Robin Morgan (1981): Blood Types: An Anatomy of Kin, reprinted in The Word of a Woman: Feminist Dispatches 1968–1992, pp. 115–120.

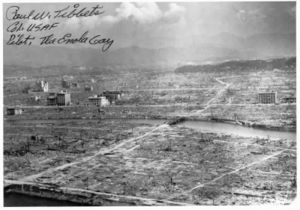

Sixty-one years ago today, at 8:15am in the morning, Thomas Ferebee, acting under the direct command of Paul Tibbets, on the orders of the United States government, dropped an atomic bomb over the city center of Hiroshima, Japan. When the bomb was dropped the city had a population of about 255,000 people. About 70,000–80,000 people were instantly killed by the shockwave, fireball, and radiation. By the end of 1945, tens of thousands more had died from their wounds, from radiation sickness, and from cancer related to the radioactivity. It’s estimated that about 140,000 people — more than half the population of the city — died in the nuclear massacre. The overwhelming majority of people killed were civilians: Hiroshima had only a couple of relatively unimportant military bases, and they were located on the edges of town, miles away from ground zero in the central city.

Sixty-one years ago today, at 8:15am in the morning, Thomas Ferebee, acting under the direct command of Paul Tibbets, on the orders of the United States government, dropped an atomic bomb over the city center of Hiroshima, Japan. When the bomb was dropped the city had a population of about 255,000 people. About 70,000–80,000 people were instantly killed by the shockwave, fireball, and radiation. By the end of 1945, tens of thousands more had died from their wounds, from radiation sickness, and from cancer related to the radioactivity. It’s estimated that about 140,000 people — more than half the population of the city — died in the nuclear massacre. The overwhelming majority of people killed were civilians: Hiroshima had only a couple of relatively unimportant military bases, and they were located on the edges of town, miles away from ground zero in the central city.