Over My Shoulder #12: Michael Fellman (2002), The Making of Robert E. Lee

You know the rules. Here’s the quote. This is from Chapter 4 (Race and Slavery

of Michael Fellman’s The Making of Robert E. Lee (2000). Of course I’ve written about this before, in GT 2005-01-03: Robert E. Lee owned slaves and defended slavery. I picked up Fellman’s book as another source to consult over the relevant sections of WikiPedia:Robert E. Lee. The passage contains some new material that I hadn’t been aware of before. It also contains a couple of minor factual errors; see below.

No historian has established how many slaves Lee actually owned before 1857, or how much income he derived from this source. The more general point is that to some extent he was personally involved in slave owning his whole adult life, as was the norm for better-off Southerners, even those who did not own plantations. Unlike many other slaveholders in Baltimore, for example, he did not manumit his personal slaves while he lived in that city and, indeed, recoiled at the thought of losing them. He carried them back with him when he returned to Virginia.

When his father-in-law died, late in 1857, Lee was left with the job of supervising Arlington and the various other Custis estates, perhaps as many as three others. Moreover, the Custis will specified that these slaves be freed by January 1, 1863 {sic–see below –RG}; therefore Lee had the dual tasks of managing these slaves in the interim and then freeing them, immersing him in the contradictions of owning, protecting, and exploiting people of a different and despised race. It was very likely that the Custis slaves knew that they were to be freed, which could have only made Lee’s efforts to succor, discipline, and extract labor from them in the meantime considerably more difficult.

Faced with this set of problems, Lee attempted to hire an overseer. He wrote to his cousin Edward C. Turner,

I am no farmer myself & do not expect to be always here. I wish to get an energetic honest farmer, who while he will be considerate & kind to the negroes, will be firm & make them do their duty.Such help was difficult to find or to retain, and despite himself Lee had to take a leave of absence from the army for two years to become a slave manager himself, one who doubtless tried to combine kindness with firmness but whose experience was altogether unhappy. Any illusions he may have had about becoming a great planter, which apparently were at least intermittent, dissipated dramatically as he wrestled with workers who were far less submissive to his authority than were enlisted men in the army. The coordination and discipline central to Lee’s role in the army proved less compatible with his role as manager of slaves than he must have expected.Sometimes, the carrot and the stick both worked ineffectively. On May 30, 1858, Lee wrote his son Rooney,

I have had some trouble with some of the people. Reuben, Parks & Edward, in the beginning of the previous week, rebelled against my authority–refused to obey my orders, & said they were as free as I was, etc., etc.–I succeeded in capturing them & lodged them in jail. They resisted till overpowered & called upon the other people to rescue them.Enlightened masters in the upper South often sent their rebellious slaves to jail, where the sheriff would whip them, presumably dispassionately, rather than apply whippings themselves. Whatever happened in the Alexandria jail after this event, less than two months later Lee sent these three men down under lock and key to the Richmond slave trader William Overton Winston, with instructions to keep them in jail until Winston could hire them out togood & responsiblemen in Virginia, for a term lasting until December 31, 1862, by which time the Custis will stipulated that they be freed. Lee also noted to Winston, in a rather unusual fashion,I do not wish these men returned here during the usual holy days, but to be retained until called for.He hoped to quarantine his remaining slaves against these three men, to whom the deprivation of the customary Christmas visits would be a rather cruel exile, though well short, of course, of being sold to the cotton fields of the Deep South. At the same time, Lee sent along three women house slaves to Winston, adding,I cannot recommend them for honesty.Lee was packing off the worst malcontents. More generally, as he wrote in exasperation to Rooney, who was managing one of the other Custis estates at the time, so few of the Custis slaves had been broken to hard work in their youth thatit would be accidental to fall in with a good one.This sort of snide commentary about inherent slave dishonesty and laziness was the language with which Lee expressed his racism; anything more vituperative and crudely expressed would have diminished his gentlemanliness. Well-bred men expressed caste superiority with detached irony, not with brutal oaths about

niggers.The following summer, Lee conducted another housecleaning of recalcitrant slaves, hiring out six more to lower Virginia. Two, George Wesley and Mary Norris {sic–see below –RG}, had absconded that spring but had been recaptured in Maryland as they tried to reach freedom in Pennsylvania.

As if this were not problem enough, on June 24, 1859, the New York Tribune published two letters that accused Lee–while calling him heir to the

Father of this free country–of cruelty to Wesley and Norris {sic–see below –RG}.They had not proceeded far [north] before their progress was intercepted by some brute in human form, who suspected them to be fugitives.They weretransported back, taken in a barn, stripped, and the men [sic] received thirty and nine lashes each [sic], from the hands of the slave-whipper … when he refused to whip the girl … Mr. Lee himself administered the thirty and nine lashes to her. They were then sent to the Richmond jail.Lee did not deign to respond to this public calumny. All he said at that time was to Rooney:The N.Y. Tribune has attacked me for the treatment of your grandfather’s slaves, but I shall not reply. He has left me an unpleasant legacy.Remaining in dignified silence then, Lee continued to be agonized by this accusation for the rest of his life. Indeed, in 1866, when the Baltimore American reprinted this old story, Lee replied in a letter that might have been intended for publication,the statement is not true; but I have not thought proper to publish a contradiction, being unwilling to be drawn into a newspaper discussion, believing that those who know me would not credit it; and those who do not, would care nothing about it.With somewhat less aristocratic detachment, Lee wrote privately to E. S. Quirk of San Fransisco aboutthis slander … There is not a word of truth in it. … No servant, soldier, or citizen that was ever employed by me can with truth charge me with bad treatment.That Lee personally beat Mary Norris seems extremely unlikely, and yet slavery was so violent that it cast all masters in the roles of potential brutes. Stories such as this had been popularized earlier in the 1850s by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and they stung even the most restrained of masters, who understood that kindness alone would have been too indulgent, and corporal punishment (for which Lee substituted the euphemism

firmness) was an intrinsic and necessary part of slave discipline. Although it was supposed to be applied only in a calm and rational manner, overtly physical domination of slaves, unchecked by law, was always brutal and potentially savage.–Michael Fellman (2000), The Making of Robert E. Lee. New York: Random House. 64–67

No servant, soldier, or citizen that was ever employed by Robert E. Lee could with truth charge him with bad treatment. Except for having enslaved them.

The letters to the Trib are online at Letter from A Citizen

(dated June 21, 1859) and Some Facts That Should Come to Light (dated June 19, 1859). Wesley Norris told his own story in 1866 after the war; it was printed in the National Anti-Slavery Standard on April 14, 1866.

Although Lee acted as if the will provided for him to keep the slaves until the last day of 1862, what Custis’s will actually said was And upon the legacies to my four granddaughters being paid, and my estates that are required to pay the said legacies, being clear of debts, then I give freedom to my slaves, the said slaves to be emancipated by my executors in such manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper, the said emancipation to be accomplished in not exceeding five years from the time of my decease.

(Meaning that at the very latest the slaves should have been manumitted by October 10, 1862, the fifth anniversary of Custis’s death.) Fellman also seems to have misread the primary sources, which state that three slaves tried to leave in 1859 — Wesley Norris, Mary Norris, and a cousin whose name I haven’t yet been able to find. Mary and Wesley were the children of Sally Norris. It’s possible that Fellman misread a reference to a George,

on the one hand, and Wesley and Mary Norris,

on the other; in which case the third might have been George Clarke or George Parks. I’ll let you know if I find out more later.

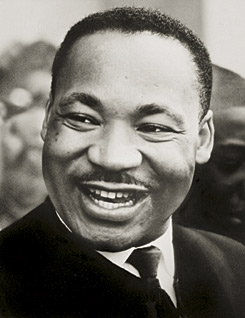

Today is Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a day to honor the life and the thought of Dr. King — a hagiographed, ignored, misunderstood, overrated, and indispensable man; one of our greatest Southern heroes; an agitator and a moral witness who gave long years of his life to the cause of the Freedom Movement, and who — underneath the television specials and the holy martyr imagery that so often serves to obscure and empty out his real, fallible, challenging, essential vision — played a vital role (together with

Today is Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a day to honor the life and the thought of Dr. King — a hagiographed, ignored, misunderstood, overrated, and indispensable man; one of our greatest Southern heroes; an agitator and a moral witness who gave long years of his life to the cause of the Freedom Movement, and who — underneath the television specials and the holy martyr imagery that so often serves to obscure and empty out his real, fallible, challenging, essential vision — played a vital role (together with

Whatever the truth, [by fall 1955] Jo Ann Robinson, Mary Fair

Burks, and the other [Women’s Political Council] members were tired

of searching for the perfect symbol for their cause. No longer

would they consult with male leaders about whether to stay off the

busses. Their plans for a boycott were ready, and, at the very

first opportunity, they would be put into effect, no matter what

the men said. The black women of Montgomery, Robinson said later,

Whatever the truth, [by fall 1955] Jo Ann Robinson, Mary Fair

Burks, and the other [Women’s Political Council] members were tired

of searching for the perfect symbol for their cause. No longer

would they consult with male leaders about whether to stay off the

busses. Their plans for a boycott were ready, and, at the very

first opportunity, they would be put into effect, no matter what

the men said. The black women of Montgomery, Robinson said later,

On December 1, 1955, less than two months after Mary Louise Smith’s arrest

[for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus], Rosa Parks waited for

a bus to take her home from work. She was just steps away from the Winter

Building, where the order had been given in 1861 to fire on Fort Sumter and

ignite the Civil War. Shortly after five o’clock, a bus pulled up to the stop.

Absorbed in thought about an NAACP workshop she was planning for that weekend,

Mrs. Parks didn’t notice the driver until after she had paid her money and

boarded. As she sank into a seat in the black section’s front row, she

realized with a jolt that he was the same man who’d thrown her off some

twelve years before. The bus lumbered down Montgomery Street and stopped in

front of the Empire Theater, where several whites got on and sat down in

the first ten rows. One man was left standing. The driver turned to Parks and

the other blacks sitting in the next row.

On December 1, 1955, less than two months after Mary Louise Smith’s arrest

[for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus], Rosa Parks waited for

a bus to take her home from work. She was just steps away from the Winter

Building, where the order had been given in 1861 to fire on Fort Sumter and

ignite the Civil War. Shortly after five o’clock, a bus pulled up to the stop.

Absorbed in thought about an NAACP workshop she was planning for that weekend,

Mrs. Parks didn’t notice the driver until after she had paid her money and

boarded. As she sank into a seat in the black section’s front row, she

realized with a jolt that he was the same man who’d thrown her off some

twelve years before. The bus lumbered down Montgomery Street and stopped in

front of the Empire Theater, where several whites got on and sat down in

the first ten rows. One man was left standing. The driver turned to Parks and

the other blacks sitting in the next row.