Over My Shoulder #39: Garrison on radicalism, electoral abolitionism and third-party politics. From Henry Mayer’s All On Fire.

Pick a quote of one or more paragraphs from something you’ve read, in print, over the course of the past week. (It should be something you’ve actually read, and not something that you’ve

read

a page of just in order to be able to post your favorite quote.)Avoid commentary above and beyond a couple sentences, more as context-setting or a sort of caption for the text than as a discussion.

Quoting a passage doesn’t entail endorsement of what’s said in it. You may agree or you may not. Whether you do isn’t really the point of the exercise anyway.

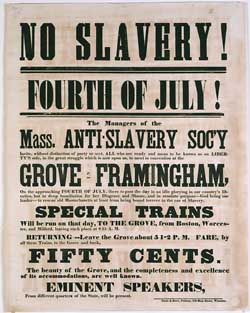

Here’s the quote. This is from Henry Mayer’s masterful biography, All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. I was re-reading it recently because of an interesting debate over the Ron Paul campaign on LeftLibertarian2, in particular some interesting comments by Brad Spangler, who has been beating the anti-electioneering drum for some time, to the effect that he thought support for Ron Paul represented progress in people who would be otherwise be state liberals or state conservatives, but that the real shame was when radical libertarians, who ought to know better

got sucked in to the same constitutional-statist song and dance.

Garrison agreed with [Abby Kelley and Stephen Foster] that the allure of the presidential campaign threatened the movement’s identity. Abolitionists should not

bow down to the house of Rimmon,alluding to the parable (2 Kings 5:18) illustrating the dangers of false worship and conformity with outmoded rituals and reprehensible customs. The first duty of abolitionists, he concluded, was to avoid becoming Republicans. To the Fosters’ intense annoyance, however, he argued that theamount of consciencein the party and the sectional basis of its opposition to the slave power made it a political entity that the movement had to take seriously. Kelley conceded that the party may bethe work of our hands,but she insisted that suchprogeny,like other children, requireda great deal of reproof to bring it up in the way it should go.Garrison agreed, but sweetly added that, as in child-rearing, it was important to praise the party when it tried to do good work, as it had on the issue of nonextension.That Garrison accorded the Republicans a measure of respect he had never conceded to the Liberty Party remnant should come as no surprise. He always had more interest in politicians who lifted themselves toward an acknowledgment of moral principles than he had in moralists who lowered themselves into partisan activities. For the Republicans to support and elect candidates willing to condemn slavery as wrong would be productive agitation, for it created something where nothing had previously existed. For Gerrit Smith to advance himself as a presidential candidate was ludicrous, in Garrison’s view, for he had no practical organization and demeaned himself in the futile process of making one. For Frederick Douglass to make persistent attacks on Garrisonian abolition as passé–as a phase of moral education through which the movement had inevitably traveled en route to more enlightened forms of practical agitation–was more than a continuation of their personal feud; it was the old Liberty Party idea that a token candidacy offered a greater opportunity for moral agitation than did the prophetic apostleship of Garrison. While the Republican nonextensionist approach had the virtue of exposing the constitutional compromises that prevented abolition, moreover, the Smithites continued to dwell, Garrison believed, in the realm of constitutional fantasy. They tried to claim the Framers as architects of an antislavery politics and advanced all sorts of schemes–a congressional repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law, a reconstruction of the federal judiciary through the appointment of antislavery judges, the fixing of a date certain for abolition in the states and federal control of states in

default–that had no chance of peaceably breaking the national political deadlock and, far from saving the Union, would make a military confrontation inevitable. Theirs was an oblique disunionism that masked itself behind the facade of constitutional interpretation. For Garrison thespecial workof abolition lay not in adopting the model of politics, but in creating a redemptive vision.We see what our fathers did not see; we know that they did not know.Powerful organizations never espouse great reforms, the editor told a December 1855 meeting called to celebrate the desegregation of Boston’s public schools after a decade-long struggle by abolitionists of both races. Social reform, he said, begins

in the heart of a solitary individualand grows strong amonghumble men and humble women [who], unknown to the community, without means, without power, without station, but perceiving the thing to be done … and having faith in the triumph of what is just and true, engage in the work….He always regarded the abolitionists as a saving remnant who would create the preconditions for reform. Theodore Parker compared suchnon-political reformerseither to the windlass that raises the anchor while the politicians haul in the slack or to the spinners and weavers who make the material from which politicians cut their clothes, but Garrison found the humblest metaphor of all in the baking of bread. By and by, he said with the apostle Paul,(1 Cor. 5:6). The most popular metaphor for the progress of reform in the 1850s, however, drew from both mechanics and nature.the little leaven leavens the whole lump… [and] this is the way the world is to be redeemedThe world moves,people said, having found a shorthand way of remarking social change that evoked at once the lever of Archimedes and the stubborn faith of Galileo that the earth itself revolved in obedience to higher laws.–Henry Mayer (1998), All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery, pp. 456-457.