International Ignore the Constitution Day festivities

Today is the 219th annual International Ignore the Constitution Day.

Here’s William Lloyd Garrison, in The Liberator, on December 29, 1832:

There is much declamation about the sacredness of the compact which was formed between the free and slave states, on the adoption of the Constitution. A sacred compact, forsooth! We pronounce it the most bloody and heaven-daring arrangement ever made by men for the continuance and protection of a system of the most atrocious villany ever exhibited on earth. Yes—we recognize the compact, but with feelings of shame and indignation, and it will be held in everlasting infamy by the friends of justice and humanity throughout the world. It was a compact formed at the sacrifice of the bodies and souls of millions of our race, for the sake of achieving a political object—an unblushing and monstrous coalition to do evil that good might come. Such a compact was, in the nature of things and according to the law of God, null and void from the beginning. No body of men ever had the right to guarantee the holding of human beings in bondage. Who or what were the framers of our government, that they should dare confirm and authorise such high-handed villany—such flagrant robbery of the inalienable rights of man—such a glaring violation of all the precepts and injunctions of the gospel—such a savage war upon a sixth part of our whole population?—They were men, like ourselves—as fallible, as sinful, as weak, as ourselves. By the infamous bargain which they made between themselves, they virtually dethroned the Most High God, and trampled beneath their feet their own solemn and heaven-attested Declaration, that all men are created equal, and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights—among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. They had no lawful power to bind themselves, or their posterity, for one hour—for one moment—by such an unholy alliance. It was not valid then—it is not valid now. Still they persisted in maintaining it—and still do their successors, the people of Massachussetts, of New-England, and of the twelve free States, persist in maintaining it. A sacred compact! A sacred compact! What, then, is wicked and ignominious?

… It is said that if you agitate this question, you will divide the Union. Believe it not; but should disunion follow, the fault will not be yours. You must perform your duty, faithfully, fearlessly and promptly, and leave the consequences to God: that duty clearly is, to cease from giving countenance and protection to southern kidnappers. Let them separate, if they can muster courage enough—and the liberation of their slaves is certain. Be assured that slavery will very speedily destroy this Union, if it be left alone; but even if the Union can be preserved by treading upon the necks, spilling the blood, and destroying the souls of millions of your race, we say it is not worth a price like this, and that it is in the highest degree criminal for you to continue the present compact. Let the pillars thereof fall—let the superstructure crumble into dust—if it must be upheld by robbery and oppression.

— William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator (1832-12-29): On the Constitution and the Union

Here’s Lysander Spooner, in No Treason (1867-1870):

The practical difficulty with our government has been, that most of those who have administered it, have taken it for granted that the Constitution, as it is written, was a thing of no importance; that it neither said what it meant, nor meant what it said; that it was gotten up by swindlers, (as many of its authors doubtless were,) who said a great many good things, which they did not mean, and meant a great many bad things, which they dared not say; that these men, under the false pretence of a government resting on the consent of the whole people, designed to entrap them into a government of a part; who should be powerful and fraudulent enough to cheat the weaker portion out of all the good things that were said, but not meant, and subject them to all the bad things that were meant, but not said. And most of those who have administered the government, have assumed that all these swindling intentions were to be carried into effect, in the place of the written Constitution. Of all these swindles, the treason swindle is the most flagitious. It is the most flagitious, because it is equally flagitious, in principle, with any; and it includes all the others. It is the instrumentality by which all the others are mode effective. A government that can at pleasure accuse, shoot, and hang men, as traitors, for the one general offence of refusing to surrender themselves and their property unreservedly to its arbitrary will, can practice any and all special and particular oppressions it pleases.

The result — and a natural one — has been that we have had governments, State and national, devoted to nearly every grade and species of crime that governments have ever practised upon their victims; and these crimes have culminated in a war that has cost a million of lives; a war carried on, upon one side, for chattel slavery, and on the other for political slavery; upon neither for liberty, justice, or truth. And these crimes have been committed, and this war waged, by men, and the descendants of men, who, less than a hundred years ago, said that all men were equal, and could owe neither service to individuals, nor allegiance to governments, except with their own consent.

… Inasmuch as the Constitution was never signed, nor agreed to, by anybody, as a contract, and therefore never bound anybody, and is now binding upon nobody; and is, moreover, such an one as no people can ever hereafter be expected to consent to, except as they may be forced to do so at the point of the bayonet, it is perhaps of no importance what its true legal meaning, as a contract, is. Nevertheless, the writer thinks it proper to say that, in his opinion, the Constitution is no such instrument as it has generally been assumed to be; but that by false interpretations, and naked usurpations, the government has been made in practice a very widely, and almost wholly, different thing from what the Constitution itself purports to authorize. He has heretofore written much, and could write much more, to prove that such is the truth. But whether the Constitution really be one thing, or another, this much is certain — that it has either authorized such a government as we have had, or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case, it is unfit to exist.

–Lysander Spooner, No Treason No. 2 and No. 6

Here’s me, from last year’s celebration in the Rad Geek People’s Daily:

You, too, can celebrate

Ignore the Constitution Day! Today, completely ignore all claims to authority granted in the Constitution. Live your life as if the Constitution had no more claim on you than the decrees of Emperor Norton. Enjoy your rights under natural law; you have them whether or not the Constitution says one mumbling word for them. While you’re at it, treat the Constitution as completely irrelevant in political arguments too; instead of complaining that unbridled war powers for the President are unconstitutional, for example, complain that they are evil; instead of reciting that damn Davy Crocket bed-time story again and complaining that government-controlled disaster relief is unconstitutional, complain that government-controlled disaster relief is foolish and deadly. (If the Constitution clearly authorized unilateral war powers for the President, or abusive and incompetant government-controlled disaster relief, would that make it okay?) And, hell, while you’re at it, quit complaining that forced Constitution Day celebrations may be unconstitutional; complain instead that they force children to participate in cultish praise for the written record of a naked usurpation.Just go ahead. Ignore the Constitution for a day. See what happens. Who’s it gonna hurt? And if your political reasoning becomes sharper, your discourse no longer bogs down in a bunch of pseudo-legal mummeries, and you have a pleasant day without having to ask anybody’s permission for it, then I suggest you continue the celebration, tomorrow, and every day thereafter.

I think that legalism is an insidious error that liberals and libertarians alike are all too prone to fall into. In fact the rule of law

is something to be hoped for only insofar as the laws are just: rigorously enforcing a wicked law–even if that law is duly published and generally formulated–is just relentlessness, not virtue. And in our bloodstained age it is as obvious as anything that many laws are very far from being just. But one way of trying to accomodate this point, while entirely missing it, is to throw your weight behind some Super-Duper Law that is supposed to condemn the little-bitty laws that you consider unjustifiable. Besides taking the focus away from creative extremism and direct action, and leaving power in the hands of government-appointed conspiracies of old white dudes in black robes, this strategy also amounts to little more than a stinking red herring. It diverts the inquiry from the obvious injustices of a State that systematically robs, swindles, extorts, censors, proscribes, beats, cuffs, jails, exiles, murders, bombs, burns, starves countless innocent people in the name of its compelling State interests,

and puts the focus the powers that are or are not delegated to the government by another damn written law. As if the contents of that law had any more right to preempt considerations of justice than the subordinate laws supposedly enacted under its authority. Those who have spent their days trying to find a lost Constitution under the sofa cushions are engaged in a massive, sophisticated, intricately argued irrelevancy. I’d compare it to debating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, but that would be grossly unfair–to Scholastic metaphysicians.

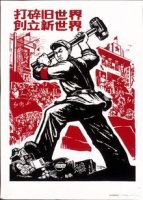

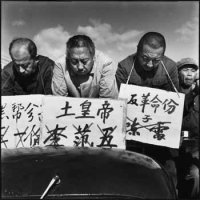

The Great Conservative Cultural Revolution is a great revolution that touches people to their very souls and constitutes a new stage in the development of the conservative revolution in our country, a deeper and more extensive stage. At present, our objective is to criticize and repudiate the reactionary far-left academic

The Great Conservative Cultural Revolution is a great revolution that touches people to their very souls and constitutes a new stage in the development of the conservative revolution in our country, a deeper and more extensive stage. At present, our objective is to criticize and repudiate the reactionary far-left academic

Now, far be it from me to stand between the Red State Guards and their patriotic duty of shaming dissenting professors for their

Now, far be it from me to stand between the Red State Guards and their patriotic duty of shaming dissenting professors for their