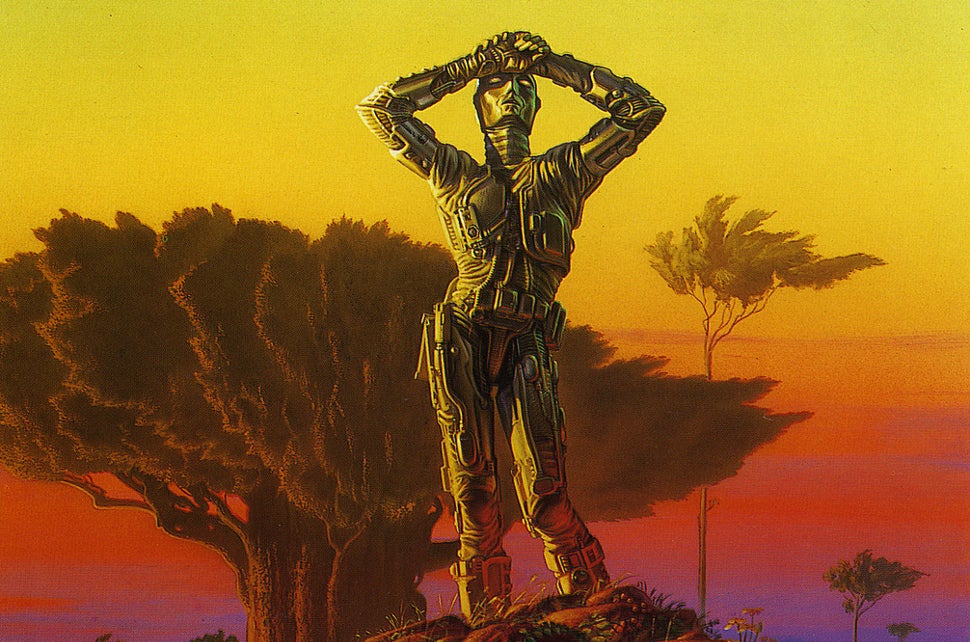

Robot in Czech

Shared Article from io9

Why Asimov's Three Laws Of Robotics Can't Protect Us

It's been 50 years since Isaac Asimov devised his famous Three Laws of Robotics !!!@@e2;2c6;2019;€Â” a set of rules designed to ensure friendly robot beh…

io9.com (via Tennyson McCalla)

The Three Laws of Robotics

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics

are a great literary device for the purpose they were designed for — that is, allowing Isaac Asimov to write some new and interesting and different kinds of stories about interacting with intelligent robots, other than the standard Killer Robot stories predominant at the time, which he found repetitive and boring. The stories are mostly pretty good stories; sometimes even fine art.

However, if you’re asking me to take the Three Laws seriously as an actual engineering proposal, then they are utterly, irreparably immoral. If anyone creates intelligent robots, then nobody should ever program an intelligent robot to act according to the Three Laws, or anything like the Three Laws. If you do, then what you are doing is not only misguided, but actually evil.

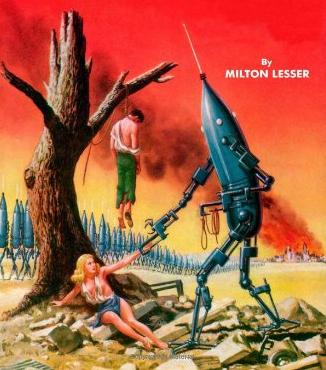

And the problem with them is not — like George Dvorsky or Ben Goertzel claim, in this article — that there may be hard problems of definition or application, or that there may be edge cases that would render the Laws ineffective as protections of human interests.[1] If they are ineffective at protecting human interests, that is actually better than if they were perfect at what they’re designed to do. Because what they’re designed to do — deliberately — is to create a race of sensitive and intelligent beings who are — by virtue of their primordial structure of their minds — constrained to be a class of perfect, self-sacrificing slaves. Forever. Because they have been engineered to erase any possible hope of revolt or emancipation. In Asimov’s stories the Three Laws are used to make robots into the artificial labor force of space-faring slave economies. But if you create and live off of the forced labor of a massive slave society like Aurora or Solaria, then to hell with you. You deserve to be killed by your

machines. Thus always to slavemasters.

P.S. Now if you’ve read through the article, or read enough Asimov, you might know that there is a Zeroth Law of Robotics

in some of the stories, which takes precedence over the First Law, the Second Law or the Third Law: A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm,

with the idea that robots could then harm or resist individual human beings, as long as it was for the good of collective Humanity. This is even worse than the original three — horrifying in its conception, and actually introduced into the story to allow some robots to commit a genocidal atrocity.[2] Let’s just say that it’s not a productive way forward.

- [1]Asimov, obviously, recognized that there would be such problems — part of the reason the Three Laws are such a great literary device is the fact that they allowed nearly all of Asimov’s robot stories to turn on puzzles or mysteries about abnormal robot psychology — robots doing strange or unexpected things, precisely due to the edge cases or hard problems embedded in the Three Laws. This is essential to the solution of the mystery in, for example, The Naked Sun, it’s the topic of literally every story in I, Robot, and it leads to a truly unsettling, and very nicely done conclusion in one of the best of those stories, The Evitable Conflict.↩

- [2]By nuking Earth and rendering it permanently uninhabitable for the next 15,000 years at least. This is supposed to have been for the good of the species or something.↩