11:02am. 67 years. 74,000 souls.

Sixty-seven years ago today:

Harry S. Truman, August 9, 1945.

We won the race of discovery against the Germans….

In his radio address on August 9, Truman described Hiroshima, a port city of some 255,000 people, a military base,

and then said, That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.

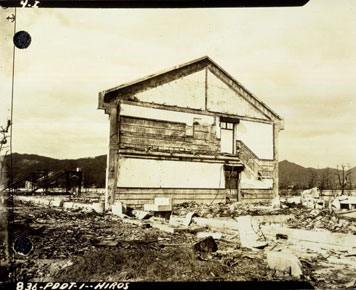

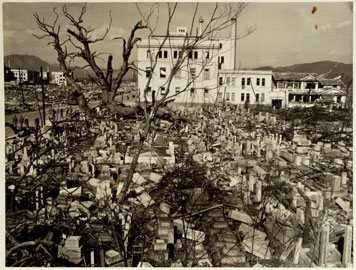

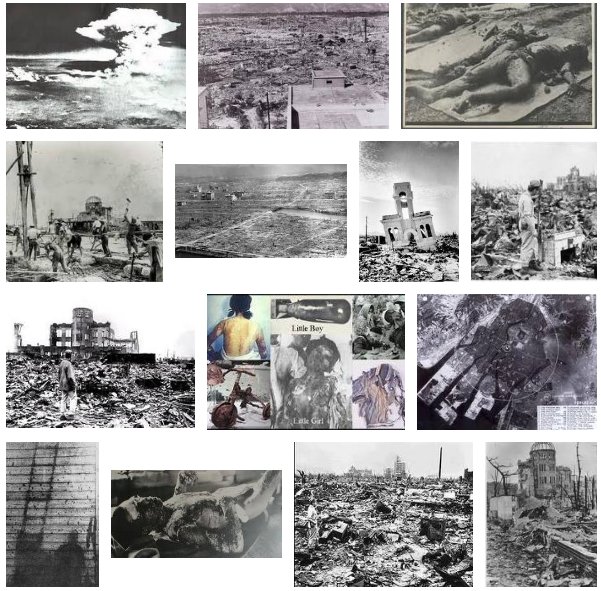

The bomb was dropped on the city center, far away from military installations. About 85% of the people killed in Hiroshima were civilians — about 120,000 of the 140,000 men, women and children killed. The atomic bombing incinerated nine-tenths of the city, and it killed more than half of the entire population.

Meanwhile, on the very same day that President Harry Truman recorded this message, without warning, before the Japanese government’s war council had even had a chance to meet to discuss the possibility of surrender, at 11:02am, on August 9, 1945, bombadier Captain Kermit Beahan, as part of the United States Army Air Forces, acting on Truman’s orders, dropped a plutonium bomb on Nagasaki, an industrial center and seaside resort town. At the time it was one of the largest ports in Japan, with about 240,000 people. The bomb and its immediate after-effects destroyed the city, and killed about a third of the people living in Nagasaki, some 74,000 men, women and children, dead.

In Nagasaki, like in Hiroshima, on a bright morning in August, with a sudden flash, brighter than the sun, a city was converted into a scene of hell. The sky went dark, buildings were thrown into the ground, and everything began to burn. People staggered through the ruins, with their eyes blinded, with their clothing burned off their bodies, with their own skin and faces burned off in the heat. Everyone was desperate for water, because they were burning, because everything was unbearably hot. They begged soldiers for water from their canteens; they drowned themselves in cisterns. Later, black rain began to fall from the darkened sky. They thought it was a deliverance. They tried to catch the black rain on their tongues, or they caught it and drank it out of cups. But they didn’t know that the rain was fallout. They didn’t know that it was full of radiation and as they drank it it was burning them away from the inside. All told, between these two deliberate atomic bombings of civilian centers, about 210,000 people were killed — vaporized or carbonized by the heat, crushed to death in the shockwave, burned to death, killed quickly or slowly by radiation poisoning and infections and cancers eating their bodies alive.

What else is there to say on a day like today?

Having found the bomb, we have used it.

… on Hiroshima, a military base…

We wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.

We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor …

We have used it … against those who starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war …

We have used it in order to shorten the agony of war.

See also:

- GT 2005-08-09: A day that will live in infamy

- Ralph Raico, Antiwar.com (2009-08-05): Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- John Pilger (2010-08-06): The Lies of Hiroshima Are The Lies of Today

- Design Observer (November, 2008): Hiroshima: The Lost Photographs

- Hiroshima, the pictures they didn’t want us to see

The audio clip above is from a recording of President Harry S. Truman’s radio report on the Potsdam conference, recorded by CBS on August 9, 1945 in the White House. The song linked to above is a recording of Oppenheimer (1997), by the British composer Jocelyn Pook. The voice that you hear at the beginning is Robert Oppenheimer, in an interview many years after the war, talking about his thoughts at the Trinity test

, the first explosion of an atomic bomb in the history of the world, on July 16th, 1945.