John D. Rockefeller, Jr., speaking to assembled Colorado miners, September 20, 1915.

We are all partners in a way. Capital can’t get along without you men, and you men can’t get along

without capital. When anybody comes along and tells you that capital and labor can’t get along

together that man is your worst enemy. We are getting along friendly enough here in this mine right

now, and there is no reason why you men cannot get along with the managers of my company

when I am back in New York.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., June 10, 1914.

There was no Ludlow massacre. The engagement started as a desperate fight for life by two small

squads of militia against the entire tent colony ... There were no women or children shot by the

authorities of the State or representatives of the operators ... While this loss of life is profoundly to

be regretted, it is unjust in the extreme to lay it at the door of the defenders of law and property,

who were in no slightest way responsible for it.

From the New York World. Reprinted in Walter H. Fink, The Ludlow Massacre (1914), 7–21.

On the day of the Ludlow battle a chum and myself left the house of the Rev. J. O. Ferris, the

Episcopal minister with whom I boarded in Trinidad, for a long tramp through the hills. We walked

fourteen miles, intending to take the Colorado & Southern Railway back to Trinidad from Ludlow

station.

We were going down a trail on the mountain side above the tent city at Ludlow when my chum

pulled my sleeve and at the same instant we heard shooting. The militia were coming out of

Hastings Canyon and firing as they came. We lay flat behind a rock and after a few minutes I raised

my hat aloft on a stick. Instantly bullets came in our direction. One penetrated my hat. The

militiamen must have been watching the hillside through glasses and thought my old hat betrayed

the whereabouts of a sharpshooter of the miners.

Then came the killing of Louis Tikas, the Greek leader of the strikers. We saw the militiamen parley

outside the tent city, and, a few minutes later, Tikas came out to meet them. We watched them

talking. Suddenly an officer raised his rifle, gripping the barrel, and felled Tikas with the butt.

Tikas fell face downward. As he lay there we saw the militiamen fall back. Then they aimed their

rifles and deliberately fired them into the unconscious man's body. It was the first murder I had ever

seen, for it was a murder and nothing less. Then the miners ran about in the tent colony and

women and children scuttled for safety in the pits which afterward trapped them.

We watched from our rock shelter while the militia dragged up their machine guns and poured a

murderous fire into the arroyo from a height by Water Tank Hill above the Ludlow depot. Then came

the firing of the tents.

I am positive that by no possible chance could they have been set ablaze accidentally. The

militiamen were thick about the northwest corner of the colony where the fire started and we could

see distinctly from our lofty observation place what looked like a blazing torch waved in the midst of

militia a few seconds before the general conflagration swept through the place. What followed

everybody knows.

Sickened by what we had seen, we took a freight back into Trinidad.

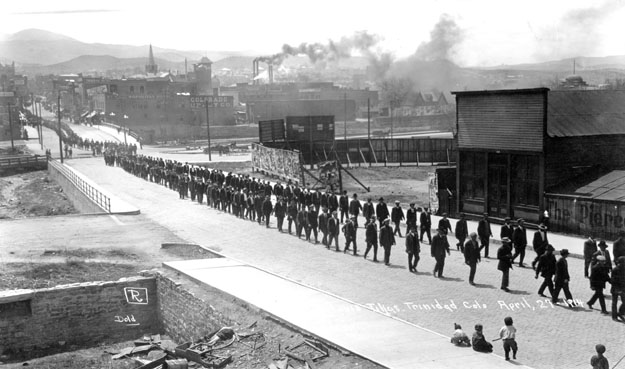

New York Times, April 21, 1914.

The Ludlow camp is a mass of charred debris, and buried beneath it is a story of horror imparalleled

in the history of industrial warfare. In the holes which had been dug for their protection

against the rifles’ fire the women and children died like trapped rats when the flames swept over

them. One pit, uncovered [the day after the massacre] disclosed the bodies of ten children and two

women.

Fellow Workers,

Today is the 94th anniversary of the Ludlow massacre–April 20th, 1914. The United Mine Workers of America led a massive strike in Rockefeller’s Colorado coal mines from 1913 to 1914, demanding an eight hour day, an increase in wages, the removal of company-hired guards from the coal pits, and freedom for workers to arrange for their own housing, choose their own doctor, and receive pay in cash instead of company scrip. Tens of thousands of workers — over 90% of the miners in the coal-pits — went on strike. When the miners went on strike, they lost everything, because they all had to live in company towns, with company landlords. They lost their money; they couldn’t shop at the stores; and they were thrown out of their homes. So they set up shanty-towns on land that the union leased for them, and lived in tents high in the hills through the long winter months of a bitter strike. The company hired guards from private detective agencies, and they got the governor to call up the Colorado National Guard on their behalf. On April 20th, the National Guard and the company thugs pretended to negotiate with Louis Tikas while setting up machine-guns in the high-points around the camps. They fired down into shanty-town and, after many of the strikers dug into the ground for cover, they torched the tents. By the end of the night 45 people were dead–32 of them women and children–shot, smothered, or burned alive. They were murdered by company death squads and by agents of the State, in order to defend John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s laws and his legally-fabricated claims to property that he never worked, and had barely ever seen.

Howard Zinn, Declarations of Independence.

As I read about this, I wondered why this extraordinary event, so full of drama, so peopled by

remarkable personalities, was never mentioned in the history books. Why was this strike, which cast

a dark shadow on the Rockefeller interests and on corporate America generally, considered less

important than the building by John D. Rockefeller of the Standard Oil Company, which was looked

on as an important and positive event in the development of American industry?

I knew there was no secret meeting of industrialists and historians to agree to emphasize the

admirable achievements of the great corporations and ignore the bloody costs of industrialization in

America. But I concluded that a certain unspoken understanding lay beneath the writing of

textbooks and the teaching of history: that it would be considered bold, radical, perhaps even

communist

to emphasize class struggle in the United States, a country where the dominant

ideology emphasized the oneness of the nation We the People, in order to…etc., etc.

and

the glories of the American system.

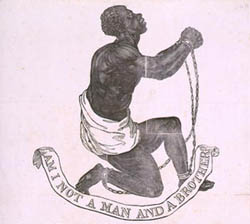

An anonymous proletarian.

First printed by the Industrial Workers of the World in 1908.

We have fed you all for a thousand years

And you hail us still unfed

Though there’s never a dollar of all your wealth

But marks the workers dead

We have yielded our best to give you rest

And you lie on crimson wool

But if blood be the price of all your wealth

Good God we have paid in full

There is never a mine blown skyward now

But we’re buried alive for you

There’s never a wreck drifts shoreward now

But we are its ghastly crew

Go reckon our dead by the forges red

And the factories where we spin

If blood be the price of your cursèd wealth

Good God we have paid it in

We have fed you all for a thousand years

For that was our doom, you know

From the days when you chained us in your fields

To the strike a week ago

You have taken our lives, and our husbands and wives

And we’re told it’s your legal share

But if blood be the price of your lawful wealth

Good God we bought it fair.

Further reading: