Sad news today. From UtahPhillips.org:

May 24, 2008

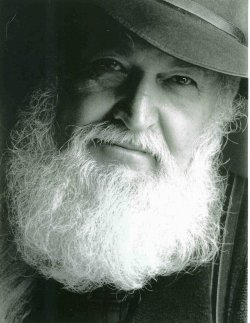

Folksinger, Storyteller, Railroad Tramp Utah Phillips Dead at 73

Nevada City, California:

Utah Phillips, a seminal figure in American folk music who performed extensively and tirelessly for

audiences on two continents for 38 years, died Friday of congestive heart failure in Nevada City,

California a small town in the Sierra Nevada mountains where he lived for the last 21 years with his

wife, Joanna Robinson, a freelance editor.

Born Bruce Duncan Phillips on May 15, 1935 in Cleveland, Ohio, he was the son of labor organizers.

Whether through this early influence or an early life that was not always tranquil or easy, by his

twenties Phillips demonstrated a lifelong concern with the living conditions of working people. He

was a proud member of the Industrial Workers of the World, popularly known as the

Wobblies,

an organizational artifact of early twentieth-century labor struggles that has seen

renewed interest and growth in membership in the last decade, not in small part due to his efforts

to popularize it.

Phillips served as an Army private during the Korean War, an experience he would later refer to as

the turning point of his life. Deeply affected by the devastation and human misery he had

witnessed, upon his return to the United States he began drifting, riding freight trains around the

country. His struggle would be familiar today, when the difficulties of returning combat veterans are

more widely understood, but in the late fifties Phillips was left to work them out for himself.

Destitute and drinking, Phillips got off a freight train in Salt Lake City and wound up at the Joe Hill

House, a homeless shelter operated by the anarchist Ammon Hennacy, a member of the Catholic

Worker movement and associate of Dorothy Day.

Phillips credited Hennacy and other social reformers he referred to as his elders

with having

provided a philosophical framework around which he later constructed songs and stories he intended

as a template his audiences could employ to understand their own political and working lives. They

were often hilarious, sometimes sad, but never shallow.

He made me understand that music must be more than cotton candy for the ears,

said

John McCutcheon, a nationally-known folksinger and close friend.

In the creation of his performing persona and work, Phillips drew from influences as diverse as

Borscht Belt comedian Myron Cohen, folksingers Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, and Country stars

Hank Williams and T. Texas Tyler.

A stint as an archivist for the State of Utah in the 1960s taught Phillips the discipline of historical

research; beneath the simplest and most folksy of his songs was a rigorous attention to detail and

a strong and carefully-crafted narrative structure. He was a voracious reader in a surprising variety

of fields.

Meanwhile, Phillips was working at Hennacy’s Joe Hill house. In 1968 he ran for a seat in the U.S.

Senate on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket. The race was won by a Republican candidate, and

Phillips was seen by some Democrats as having split the vote. He subsequently lost his job with the

State of Utah, a process he described as blacklisting.

Phillips left Utah for Saratoga Springs, New York, where he was welcomed into a lively community of

folk performers centered at the Caffé Lena, operated by Lena Spencer.

It was the coffeehouse, the place to perform. Everybody went there. She fed everybody,

said John Che

Greenwood, a fellow performer and friend.

Over the span of the nearly four decades that followed, Phillips worked in what he referred to as

the Trade,

developing an audience of hundreds of thousands and performing in large and

small cities throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. His performing partners included

Rosalie Sorrels, Kate Wolf, John McCutcheon and Ani DiFranco.

He was like an alchemist,

said Sorrels, He took the stories of working people and

railroad bums and he built them into work that was influenced by writers like Thomas Wolfe, but

then he gave it back, he put it in language so the people whom the songs and stories were about

still had them, still owned them. He didn’t believe in stealing culture from the people it was

about.

A single from Phillips’s first record, Moose Turd Pie, a rollicking story

about working on a railroad track gang, saw extensive airplay in 1973. From then on, Phillips had

work on the road. His extensive writing and recording career included two albums with Ani DiFranco

which earned a Grammy nomination. Phillips’s songs were performed and recorded by Emmylou

Harris, Waylon Jennings, Joan Baez, Tom Waits, Joe Ely and others. He was awarded a Lifetime

Achievement Award by the Folk Alliance in 1997.

Phillips, something of a perfectionist, claimed that he never lost his stage fright before

performances. He didn’t want to lose it, he said; it kept him improving.

Phillips began suffering from the effects of chronic heart disease in 2004, and as his illness kept him

off the road at times, he started a nationally syndicated folk-music radio show, Loafer’s Glory, produced at KVMR-FM and started a homeless shelter in his

rural home county, where down-on-their-luck men and women were sleeping under the manzanita

brush at the edge of town. Hospitality House opened in 2005 and continues to house 25 to 30

guests a night. In this way, Phillips returned to the work of his mentor Hennacy in the last four

years of his life.

Phillips died at home, in bed, in his sleep, next to his wife. He is survived by his son Duncan and

daughter-in-law Bobette of Salt Lake City, son Brendan of Olympia, Washington; daughter Morrigan

Belle of Washington, D.C.; stepson Nicholas Tomb of Monterrey, California; stepson and

daughter-in-law Ian Durfee and Mary Creasey of Davis, California; brothers David Phillips of Fairfield,

California, Ed Phillips of Cleveland, Ohio and Stuart Cohen of Los Angeles; sister Deborah Cohen of

Lisbon, Portugal; and a grandchild, Brendan. He was preceded in death by his father Edwin Phillips

and mother Kathleen, and his stepfather, Syd Cohen.

The family requests memorial donations to Hospitality House, P.O. Box 3223, Grass Valley,

California 95945 (530) 271-7144

http://www.hospitalityhouseshelter.org

Jordan Fisher Smith and Molly Fisk

Utah Phillips is the reason I became a Wobbly. He’s also a big part of the reason that I got as interested as I got in the anarchists and the labor radicals of the early 20th century. It’s a much poorer world now that we no longer have his voice among us; the only consolation, if there is any, is how much richer it is from having had it all these years.

The old songs, these old stories… why tell them? What do they

mean?

When I went to high school–that’s about as far as I got–reading

my U.S. history textbook, well I got the history of the ruling

class; I got the history of the generals and the industrialists and

the Presidents who didn’t get caught. How about you?

I got the history of the people who owned the wealth of the

country, but none of the history of the people who created it…

you know? So when I went out to get my first job, I went out armed

with someone else’s class background. They never gave me any tools

to understand, or to begin to control the condition of my labor.

And that was deliberate, wasn’t it? Huh? They didn’t want me to

know this. That’s why this stuff isn’t taught in the history books.

We’re not supposed to know it, to understand that. No. If I wanted

the true history of where I came from, as a member of the working

class, I had to go to my elders. Many of them, their best working

years before pensions or Social Security, gave their whole lives to

the mines, to the wheat harvests, to the logging camps, to the

railroad. Got nothing for it–just fetched up on the skids, living

on short money, mostly drunk all the time. But they lived those

extraordinary lives that can never be lived again. And in the

living of them, they gave me a history that is more profound, more

beautiful, more powerful, more passionate, and ultimately more

useful, than the best damn history book I ever read.

As I have said so often before, the long memory is the most

radical idea in America….

–Utah Phillips, The Long Memory

, on Fellow Workers (recorded with Ani DiFranco)

Mark Twain said, Those of you who are inclined to worry have the

widest selection in history.

Why complain? Try to do something about

it…. You know, it’s going on nine months now since I decided that I was

going to declare that I am a candidate for the presidency of the United

States. Oh yes: I’m going to run. … So I created my own party. It’s

called the Sloth and Indolence Party, and I am running as an anarchist

candidate, in the best sense of that word. I have studied the presidency

carefully; I have seen that our best presidents were the do-nothing

presidents: Millard Fillmore, Warren G. Harding…. When you have a

president who does things, we are all in serious trouble. If he does

anything at all–if he gets up at night to go to the bathroom–somehow,

mystically, trouble will ensue. I guarantee that if I am elected, I will

take over the White House, hang out, shoot pool, scratch my ass, and not

do a damn thing. Which is to say, if you want something done, don’t come

to do it for you; you’ve got to get together and figure out how to do it

yourselves. Is that a deal?

— Utah Phillips (1996), Candidacy, on The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere (recorded with Ani DiFranco).

I spend a lot of time these days going to demonstrations and vigils, talking to people who support the war. They can be pretty threatening. But I always find there are people there–and I don’t mean policemen, but there are people there who will protect you. I don’t go there to shout or to lecture, but to ask questions. Real questions. Questions I really need answers to.

When I joined the Army, it was kind of like somebody that I had been brought up to respect, wearing a suit and a tie, and maybe a little older, in my neighborhood. Think about yourself in your neighborhood, and this happened to you. He walked up to me, put his arm around my shoulder, and said, See that fellow on the corner there? He’s really evil, and has got to be killed. Now, you trust me; you’ll go do it for me, won’t you? Now, the reasons are a little complicated; I won’t bother to explain, but you go and do it for me, will you?

Well, if somebody did that to you in your neighborhood, you’d think it was foolish. You wouldn’t do it. Well, what makes it more reasonable to do it on the other side of the world? That’s one question.

Well, now hook it into this. If I was to go down into the middle of your town, and bomb a house, and then shoot the people coming out in flames, the newspapers would say, Homicidal Maniac!

The cops would come and they’d drag me away; they’d say You’re responsible for that!

The judge’d say, You’re responsible for that

; the jury’d say You’re responsible for that!

and they would give me the hot squat or put me away for years and years and years, you see? But now exactly the same behavior, sanctioned by the State, could get me a medal and elected to Congress. Exactly the same behavior. I want the people I’m talking to to reconcile that contradiction for themselves, and for me.

The third question–well I take that one a lot to peace people. There’s a lot of moral ambiguity going on around here, with the peace people who say, Well, we’ve got to support the troops,

and then wear the yellow ribbon, and wrap themselves in the flag. They say, Well, we don’t want what happened to the Vietnam vets to happen to these vets when they come home–people getting spit on.

Well, I think it’s terrible to spit on anybody. I think that’s a consummate act of violence. And it’s a terrible mistake, and I’m really sorry that happened. But what did happen? Song My happened; My Lai happened; the defoliation of a country happened; tons of pesticides happened; 30,000 MIAs in Vietnam happened. And it unhinged some people–made them real mad. And what really, really made them mad, was the denial of personal responsibility–saying, I was made to do it; I was told to do it; I was doing my duty; I was serving my country.

Well, we’ve already talked about that.

Now, it is morally ambiguous to wrap yourself in the flag and to wear those ribbons. And it borders on moral cowardice. I don’t mean to sound stern; well, yes I do, but what does the Nuremberg declaration say? There’s no superior order that can cancel your conscience. Nations will be judged by the standard of the individual. Look, the President makes choices. The Congress makes choices. The Chief of Staff makes choices. The officers make choices. All those choices percolate down to the individual trooper with his finger on the trigger. The individual private with his thumb on the button that drops the bomb. If that trigger doesn’t get pulled, if that button doesn’t get pushed, all those other choices vanish as if they never were. They’re meaningless. So what is the critical choice? What is the one we’ve got to think about and get to? And, friends, if that trigger gets pulled–if that button gets pushed, and that dropped bomb falls–and you say I support the troops,

you’re an accomplice. I don’t want to be an accomplice; do you?

And I don’t want to dehumanize anyone. I don’t want to take away anybody’s humanity. Humans are able to make moral decisions–moral, ethical decisions. What do we tell the trooper who pulls the trigger, or the soldier who turns the wheel that releases oil into the Persian Gulf, that they’re not responsible–just following orders, just doing their duty, have no choice–bypassing them, making them a part of the machine, we deny them their humanity, their responsibility for their actions and the consequences of those actions. Look, I’ve been a soldier. I don’t want any moral loophole. I need to take personal responsibility for my actions. And if we don’t learn how to do this, we’re going to keep on going to war again, and again, and again.

–Utah Phillips (1992): from The Violence Within, I’ve Got To Know

There I am in Spookaloo, city of magic, city of light, ensconced upon

my front porch in broad daylight — long about noon, my rising time —

drinking something of a potable beverage, playing my guitar, long after

everybody else in the neighborhood has packed up their lunchbox and gone

off down to Kaiser Aluminum to put in their shift. This enrages my

neighbors. One in particular across the road, little retired banker

fella, has been known to cannonball his rotundity across the road, and

stand there and publicly berate me for my sloth and indolence.

Why don’t you get a job?

he says. Lot of you heard that, I’ll bet.

Now, me being hip to the Socratic method, fires back a question. Why?

Why?

he says, taken aback. If you had a job you could make three,

four, five dollars an hour.

I said Why?

I asked, pursuing the same tack.

He said, Hell, you make three, four, five dollars an hour, you could

open a savings account, save up some of that money.

I said, Why?

He said, Well, you save up enough of that money, young fella, pretty

soon you’ll never have to work another day in your life.

I said, Hell, that’s what I’m doing right now!

–Utah Phillips (1984), in the middle of his performance of Hallelujah, I’m a

Bum! on We Have Fed You All A Thousand Years