Rapists on patrol (#3). Officer Gary Pignato, Greece, New York

(Via Drug War Chronicle Issue #584, 8 May 2009: This Week’s Corrupt Cop Stories.)

A week ago, in Greece, New York, Officer Gary Pignato, stalker, home invader, and serial rapist, was arraigned on charges that, acting under the color of law and with the extensive legally-backed powers that his badge affords, he used the threat of violent force to coerce sex from at least two unwilling women. In at least one of those cases, before he used the threat of arrest to rape her, he first picked her out, followed her back to her home in his police car, took the opportunity to get her phone number, and then, a few days later, invaded her house without permission. After raping her he kept calling her, over and over again, until she said she would expose what he was doing.

A second woman has accused a Greece police officer of using his authority to coerce her into sex.

Gary Pignato of Hilton was arraigned Tuesday on charges of third-degree bribery of a public servant, a felony; second-degree coercion, third-degree criminal trespass and official misconduct, all misdemeanors. He pleaded not guilty to all charges.

Pignato goes to trial June 1 on an earlier felony count of accepting a bribe and misdemeanor counts of coercion and official misconduct stemming from allegations that he went to a Greece woman’s home in August, then later coerced her into a sexual encounter.

According to documents filed in Greece Town Court on Tuesday, a different woman accuses Pignato of similar acts.

The woman’s name was redacted in the documents and it is the Democrat and Chronicle’s policy not to name victims of sexual crimes.

In a deposition dated April 28, the victim alleges she first met Pignato during the summer of 2005 when he followed her in his marked car as she drove into her apartment complex. She alleges he introduced himself that night, gave her his card and asked for her phone number.

Then, she alleges, a few days later she was smoking marijuana at her dining room table when Pignato walked in unannounced, told her she could be arrested and lose her children for what she was doing and said

we can make this go away.She alleges Pignato said having sex with him

would take care of it.The victim alleges they made arrangements to meet the next night. She said she drove to his house in Hilton where they engaged in sex.

She alleges Pignato continued to call her seeking sex over the next few days and finally stopped calling when she threatened to find his girlfriend and tell her what he did.

In her statement, the victim said a friend convinced her to contact authorities after news broke about Pignato’s other arrest and criminal charges.

In the August case, the victim alleges Pignato visited her home during a domestic dispute, then threatened to arrest her for violating her probation if she didn’t have sex with him.

Pignato has admitted to State Police that he had sex with that woman, but said it was consensual.

. . . Pignato, who has been suspended without pay, turned himself in to State Police Tuesday afternoon. He was released from court on his own recognizance. A court date was set for June 17, but Assistant District Attorney William Gargan said the case could go to a grand jury.

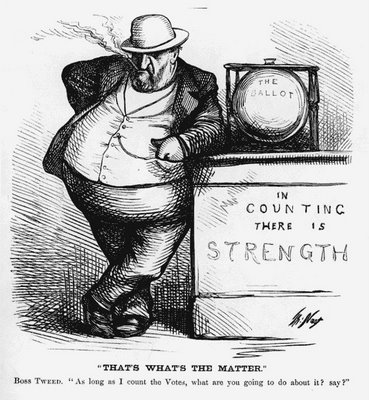

Please note that if you, or I, or anyone else without a badge and a government uniform were to follow women around, picking out victims for their special attentions, then busted into that woman’s house without permission, threatened to harm her children, threatened to draw a gun and force her into a car and carry her off to some hellhole far away where she would be locked up against their will — if you, or I, or anyone else, I say, did all these things several times, as a threat used to coerce sex from unwilling victims, then we would be treated, by the media and by the law, as rapists of the most dangerous sort and an immediate threat to everyone in the community. You or I would be jailed with an astronomical bail or no bail at all; you or I would hit with multiple aggravated felony charges and if convicted we would spend years of our lives in maximum security prisons. But because Officer Gary Pignato of Hilton, New York happens to be a police officer — because the violence he uses is violence under color of law, and because the threats he makes against his chosen targets are threats backed up by the armed force of the State, and because the women who uses those threats of violence against are suspect

women, under the special scrutiny of the police, this dangerous, heavily-armed sexual predator has been released into the community on his own recognizance, and he has been charged with nothing more than a handful of misdemeanors for the rapes and the home invasion he committed. The only felonies he’s been charged with are bribery

charges; only his betrayal of the police department, not his repeated use of his government-backed authority to coerce sex from unwilling women, is treated as serious enough to merit a felony charge.

Here’s what I said about a case with several male cops in San Antonio back in December; just replace the comments about the government’s war on sex workers with comments about the government’s war on drug users.

What as at stake here has a lot to do with the individual crimes of three cops, and it’s good to know that the police department is taking that very seriously. But while excoriating these three cops for their personal wickedness, this kind of approach also marginalizes and dismisses any attempt at a serious discussion of the institutional context that made these crimes possible — the fact that each of these three men worked out of the same office on the same shift, the way that policing is organized, the internal culture of their own office and of the police department as a whole, and the way that the so-called

criminal justice systemgives cops immense power over, and minimal accountability towards, the people that they are professedly trying to protect. It strains belief to claim that when a rape gang is being run out of one shift at a single police station, there’s not something deeply and systematically wrong with that station. If it weren’t for the routine power of well-armed cops in uniform, it would have been much harder for Victor Gonzales, Anthony Munoz, or Raymond Ramos to force their victims into theircustodyor to credibly threaten them in order to extort sex. If it weren’t for the regime of State violence that late-night patrol officers exercise, as part and parcel of their legalduties,against women in prostitution, it would have been that much harder for Gonzales and Munoz to imagine that they could use their patrol as an opportunity to stalk young women, or to then try to make their victim complicit in the rape by forcing her to pretend that the rape was in fact consensual sex for money. And if it weren’t for the way in which they can all too often rely on buddies in the precinct or elsewhere in the force to back them up, no matter how egregiously violent they may be, it would have been much harder for any of them to believe that they were entitled to, or could get away with, sexually torturing women while on patrol, while in full uniform, using their coercive power as cops.A serious effort to respond to these crimes doesn’t just require individual blame or personal accountability — although it certainly does require that. It also requires a demand for fundamental institutional and legal reform. If police serve a valuable social function, then they can serve it without paramilitary forms of organization, without special legal privileges to order peaceful people around and force innocent people into

custody,and without government entitlements to use all kinds of violence without any accountability to their victims. What we have now is not civil policing, but rather a bunch of heavily armed, violently macho, institutionally privileged gangsters in blue.