What’s really wrong with relativism?

Over in the comments on GT 2006-04-09: Freedom Movement Celebrity Deathmatch, Jeremy (of Social Memory Complex) asks the following question, referring back to an exchange I had with Lady Aster (1, 2), and an exchange that Jeremy and I had at his blog (1 et seq.):

In your reply to Aster you spoke of the danger of relativism. Is it possible for you to expand on this concept? Can you be more descriptive and perhaps specific about the danger you see in a relativist view of the morality? Or perhaps you have written about this elsewhere and can direct me to your existing writing. I only ask because we've recently discussed this and I'm interested in your argument here.

I initially posted this reply as a very long comment; after thinking about it, I decided that it would be of general enough interest, even though it’s a fairly sketchy overview, to make it a post of its own.

Jeremy, I think that the best reply partly depends on what sort of dangers you’re interested in.

I have philosophical reasons for believing that moral relativism is theoretically flawed. If relativism is intended to be a description of the logic behind people’s actual use of moral terms, then it’s not an accurate description; it’s not really a theory of morality at all, but rather a theory of something else — etiquette, taste, or, in its crudest forms, conventional wisdom or personal pleasure. If, on the other hand, it’s intended to be a normative theory about the criteria that people ought to use in making certain kinds of judgments — by, say, abandoning the morality-game’s requirements for certain kinds of consistency across differences of culture or personal psychology, and adopting some other, relativistic set of requirements — then I think that that theory is undermotivated, false, and, at least in most versions, logically incoherent. If it’s intended as a meta-ethical theory, which takes for granted the rules of the morality-game as they are, and doesn’t specifically counsel abandoning those rules, but which claims that those rules either don’t express factual claims at all, or else express factual claims that presuppose something false, then what you’ve got is not really relativism exactly, but either non-cognitivism or an error theory (respectively). I have my own logical and philosophical problems with each of those, which we can discuss at more length if you want.

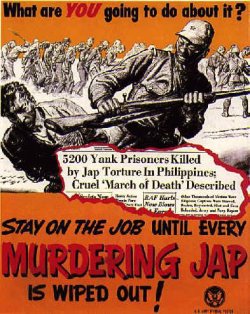

I also have reasons for thinking that relativism is a moral danger, in the sense that I believe that, under many circumstances, indulging in relativistic argument is in fact a moral vice, and that it tends to encourage other kinds of moral vice. Basically because on any form of relativism (cultural relativism, agent relativism, speaker relativism, etc.) you necessarily, in order to remain a relativist, must fail to hold some people to moral standards that it’s appropriate to hold them to, and to hold some other people to moral standards that it’s inappropriate to hold them to. It amounts to either excuse-making or bigotry, depending on the case. (For example, consider the very common, implicitly culturally-relativist claim that contemporary writers shouldn’t judge George Washington harshly for enslaving hundreds of his fellow human beings if most of his contemporaries, or at least most of the minority faction of his contemporaries whose opinions he cared about — the white and propertied ones — believed that slavery was O.K. and if Washington’s methods weren’t especially harsh by their standards. I don’t think there is any possible way to make this kind of claim without, thereby, expressing a really massive callousness toward the well-being, dignity, and rights of the hundreds of people that George Washington enslaved. Not only do I regard it as being philosophically mistaken, but the callousness itself is wrong. And if you live the kind of life that that kind of immorality accords with, well, that’s a problem with your life, not a problem with morality.)

I also have reasons for thinking that libertarians should regard relativism in general, and relativism about the duty to respect other people’s rights in particular, as a political danger. If justice is thought of as something that’s less than universally and categorically binding, which individual people or cultures of people can take or leave as it pleases them, then I don’t think it is very surprising that what will soon follow is a whole host of reasons or excuses for leaving it in favor of some putative benefit to be got through coercion. Politically speaking, I’m not just interested in theories which proclaim my reasons for not beating, burning, and bombing innocent people; I wouldn’t do that anyway, and just about nobody would support me or make excuses on my behalf if I did. I’m much more concerned with theories which proclaim George W. Bush’s or Dick Cheney’s reasons for not beating, burning, and bombing innocent people, because the problem in this case is precisely those who don’t believe that they have any personal reason not to do that.

Of course, I could instead adopt a moral theory on which it’s O.K. for them to act like that, but also O.K. for me to try to resist them, and a sociological theory which predicts that if I stick to my values and they convert to similar values, it’ll lead to a better outcome for the both of us than if we each stick to our values, or if I convert to Bush’s and Cheney’s. (Maybe that’s what Max Stirner believed.)

But, again, in addition to the theoretical and the moral problems that I’ve already mentioned, I also think that this kind of theory is unlikely to get you much political traction, because it underplays your dialectical hand. (I think that binding moral claims are really much stronger, rhetorically and dialectically, than most people seem to believe they are. Lots of people very often rule out a stark moral arguments–say against slavery, or imprisoning nonviolent drug users, or forced pregnancy, or the war on Iraq–in favor of some much more complicated technical argument, or a pseudo-conciliatory hand-wringing argument, because they dismiss the moral argument as somehow impractical,

even though it would be perfectly convincing to them, and even though they would find complicated or hand-wringing argument confusing, unfocused, or worse, if they were the ones listening to the argument. The problem in these cases is often not with the moral argument but rather with the arguer underestimating her audience.) I also think that these kind of approaches very often involve a mistake about the best target for your argument; sometimes it makes sense to try to persuade aggressors to stop being aggressive by argument, but it’s much more often the case that the smarter goal would be to try to convince other victims of aggression to resist, or at least stop collaborating with, the aggressor, and stark moral arguments against the legitimacy of the aggression are very often going to be the most effective way to inspire comrades and shame collaborators.

But, setting aside political strategy, I think the most important reasons are the moral and logical ones. The fact that relativism and relativistic arguments are dangerous to the political prospects for liberty, if that is a fact, is just a secondary reason to more strongly dislike it. The primary reason to oppose it is that the position is false, the arguments are fallacious, and the vision of human life and moral discourse that it presents — one in which people are just so many bigots and partisans, divided in our basically irreconcilable values by personal temperament or, worse, cultural or parochial loyalties, whose normative discourse consists of battering their own preferences against other people, to whom those preferences are ultimately alien, in the hope that their opponents will eventually be remade in their own image and their own preferences will triumph, through means explicitly other than rational conviction, which of course has been ruled out from the get-go by the relativist premise — is a narrow and mean and miserable thing compared to the vision on which we are, each of us, fellow citizens of a cosmopolis of all rational creatures, open to each other’s reasons and concerns, and in both amenable to, and hopefully guided by, reason, when it comes to the things that are most important to each of our individual lives. The highest form of flourishing is one in which I neither regard myself as made for the use of others, nor regard others as made for my own use, but rather see my taste and idiosyncratic projects, other people’s taste and idiosyncratic projects, and the common tastes and projects which we may agree to cultivate cooperatively, as all existing within the scope of shared and universally intelligible norms of respect, consent, humanity, and rational discourse. Relativism often advances itself as if it promoted that form of flourishing, under the veneer of a phony tolerance, but in fact to the extent that it attacks the sharedness and universal intelligibility of those norms, it is attacking that form of flourishing, and attempting to claim that tolerance means my right to make you tolerate whatever I want you to (or vice versa), since (after all) the relativistic version of tolerance can in principle include tolerance

of absolutely any value, including values for coercion, aggression, parasitism, and sadism.

I should note before I conclude that I don’t think that the argument of Aster’s which I was originally responding to is at all guilty of relativism. I think that’s a danger implicit in the kind of language she recommends, but there are other, related dangers of authoritarianism which are implicit in the kind of language that she criticizes; whichever kind of language you choose, there’s dialectical work to be done in making clear what you want to make clear while avoiding the error that the language might suggest in careless hands. And if she does at some point fall into a relativistic error about the status of rights — which as far as I know she doesn’t, and which I certainly don’t mean to attribute to her –then I’m quite certain, based on what she’s written here and elsewhere, that it’s not for some of the reasons (e.g. underestimating her audience or confusion about the appropriate audience) that I discuss here. I think all forms of relativism involve at least some of these confusions, but only some forms involve all of them.

Anyway, I hope this helps somewhat in explaining, but I think that I probably haven’t covered what you wanted me to cover in the detail that you wanted. But I think there are a lot of different points to cover, and to cover any given point more deeply and more illustratively, I’d need to know a bit more about what specific kind of dangers, and in what context of discourse, you’re interested in my views on. A conversation that I’d be happy to have in comments, for those that are interested.

Further reading:

- GT 2005-07-26: Pet Peeves

- GT 2006-09-01: One man’s reductio, GT 2004-12-05: The Humane Impaler, and GT 2003-09-30: Why There Are No Arguments for Terrorism

- G. E. Moore (1912), Ethics, Chapter III and [Chapter IV]((http://fair-use.org/g-e-moore/ethics/chapter-iv), on The Objectivity of Moral Judgments.